More historians and others have weighed in on the January 6 treasonous attempted coup, and much of the commentary can connect the Civil War and Reconstruction to what happened.

First let’s look at this post, which tells us, “Much will be said about the fact that these actions threaten the core of our democracy and undermine the rule of law. Commentators and political observers will rightly note that these actions are the result of disinformation and heightened political polarization in the United States. And there will be no shortage of debate and discussion about the role Trump played in giving rise to this kind of extreme behavior. As we have these discussions, however, we must take care to appreciate that this is not just about folks being angry about the outcome of one election. Nor should we believe for one second that this is a simple manifestation of the president’s lies about the integrity of his defeat. This is, like so much of American politics, about race, racism and white Americans’ stubborn commitment to white dominance, no matter the cost or the consequence. It is not by chance that most of the individuals who descended on the nation’s capital were white, nor is it an accident that they align with the Republican Party and this president. Moreover, it is not a coincidence that symbols of white racism, including the Confederate flag, were present and prominently displayed. Rather, years of research make clear that what we witnessed in Washington, D.C., is the violent outgrowth of a belief system that argues that white Americans and leaders who assuage whiteness should have an unlimited hold on the levers of power in this country. And this, unfortunately, is what we should expect from those whose white identity is threatened by an increasingly diverse citizenry.” After giving a valuable summary of much social science research that illuminates these actions, the post also tells us, “Of course, the iconography of the failed Confederacy, alongside other reminders of white racial violence, including the placing of a noose around a tree near the Capitol, are intentional, too. For those who broke glass in windows of the Capitol, who marched in opposition to American democracy, who held up as a model the seditious behaviors of slaveholding states, who threatened the lives of elected officials and caused chaos that lays bare the dangerous situation we are in as a country — these are not political protesters asking their government for a redress of grievances. Nor are they patriots whose actions should be countenanced in a society governed by the rule of law. Instead, we must characterize them as they are: They are a dangerous mob of grievous white people worried that their position in the status hierarchy is threatened by a multiracial coalition of Americans who brought Biden to power and defeated Trump, whom back in 2017 Ta-Nehisi Coates called the first white president. Making this provocative point, Coates wrote, ‘It is often said that Trump has no real ideology, which is not true — his ideology is white supremacy, in all its truculent and sanctimonious power.’ So, when we think about those who gathered in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday and who will surely continue their advance in opposition to democratic rule, let it not be lost on us that they do not simply come in defense of Donald Trump. They come in defense of white supremacy.”

Next let’s consider this article by historian Daniel Gullotta. It says, “Numerous individuals who breached the Capitol carried Confederate flags—the symbol adopted by those who sought to break with the United States for the purpose of defending and perpetuating slavery—for the first time in the nation’s history. In a haunting image captured by photographers Saul Loeb of AFP (above) and Mike Theiler of Reuters, we watched a man carry the Confederate flag in front of a portrait of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. As noted Civil War historian Judith Giesberg told Business Insider, ‘What that image should remind us of is that there’s a history of having violent political confrontations in Congress.’ Born in Boston in 1811, Sumner was raised in an antislavery household. He was among the ‘Conscience Whig’ faction that rejected the party’s accommodation with slavery. In 1847, Sumner declaimed against the Mexican-American War as ‘a war for the extension of slavery over a territory which has already been purged, by Mexican authority, from this stain and curse.’ In 1848, the Whigs nominated the war hero and slaveholder Zachary Taylor for president. Sumner had seen enough: he bolted to the short-lived antislavery Free Soil Party, a coalition born of Barnburner Democrats, Conscience Whigs, and the Liberty Party. Sumner was quick to make enemies in his political career. Beyond attacking Southerners, he also decried the complicity of Northerners in maintaining and profiting from slavery. Like many antislavery politicians and activists, he charged that the American political system was being held hostage by an ‘unhallowed union’ of ‘the cotton-planters and flesh-mongers of Louisiana and Mississippi and the cotton-spinners and traffickers of New England.’ Sumner remained an outspoken opponent of slavery after his election to the Senate in 1851. In the midst of the violent ‘Bleeding Kansas‘ crisis—in fact, on the eve of the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas in 1856—Sumner took to the Senate floor to deliver his blistering speech ‘The Crime Against Kansas.’ Comparing slaveholding politicians and their enablers living in free states to oligarchs, Sumner blasted at those who supported ‘the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery.’ But Sumner did not just attack in broad strokes; he personally attacked Senators James Mason of Virginia, Stephen Douglas of Illinois, and Andrew Butler of South Carolina. Sumner compared Butler to the deluded Don Quixote and accused the South Carolina slaveholder of taking ‘the harlot Slavery’ as his ‘mistress.’ Sumner’s speech sparked an immediate backlash that soon became the talk of the capital. Thomas Rivers, a congressman from Tennessee, reportedly said that ‘Mr. Sumner ought to be knocked down, and his face jumped into.’ The Washington Star defended Senator Butler, calling Sumner’s rhetorical attacks on him ‘unjust and untrue‘ and arguing that his language ‘caused a blush of shame to mantle the cheeks of all present.’ Even some of Sumner’s Republican allies believed that he had gone too far with this rhetoric, fearing the political fallout and possible threat to his personal safety.”

This, of course, led to the infamous and cowardly attack on Sumner, who was seated at his desk in the Senate chambers and unable to defend himself, by the slavery-loving South Carolinian Preston Brooks. The article continues, “Two days later, there followed one of the most infamous and troubling incidents in the history of the U.S. Congress. While Sumner was sitting at his desk on the Senate floor, he was approached by Preston Brooks, a South Carolinian congressman and a relative of Butler’s. Addressing Sumner, Brooks said, ‘I have read your speech twice over carefully, it is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.’ Brooks struck Sumner across the head with his gutta percha cane. The first blow stunned Sumner, who tried to defend himself but soon collapsed amid the onslaught of blows from Brooks. Onlookers were unable (and in some cases unwilling) to assist Sumner, since Brooks was accompanied by armed House colleagues South Carolinian Laurence Keitt and Virginian Henry Edmunson. According to Brooks, ‘towards the last [Sumner] bellowed like a calf. I wore my cane out completely but saved the head, which is gold.’ Southerners widely celebrated Brooks’s actions. Sen. Robert Toombs of Georgia (the future Confederate secretary of state) witnessed the assault and roundly approved. ‘Our approbation . . . is entire and unreserved,’ printed the Richmond Enquirer, going on to compare Sumner’s beating to the beating of a dog:

These vulgar abolitionists in the Senate are getting above themselves. They have been humored until they forget their position. They have grown saucy, and dare to be impudent to gentlemen! Now, they are a low, mean, scurvy set, with some little book learning, but as utterly devoid of spirit or honor as a pack of curs. Intrenched behind “privilege,” they fancy they can slander the South and insult its Representatives, with impunity. The truth is they have been suffered to run too long without collars. They must be lashed into submission.

“Brooks and his chief accomplice Keitt both resigned from Congress, but they were each quickly re-elected to their House seats. Back home, South Carolinians welcomed Brooks as the guest of honor at numerous parties and presented their hero with canes to replace the one broken while assaulting Sumner. One such cane bore the inscription ‘Hit him again.’ Brooks crowed that ‘the fragments of the stick are begged for as sacred relics.’ Upon Brooks’s untimely death of croup in 1857, Georgia named a county after him. Keitt went on to serve in the provisional Confederate Congress before fighting in the Confederate Army until his death at the Battle of Cold Harbor. The assault on Sumner galvanized Northerners and produced a backlash that rallied people to the Republican cause. Moderate and conservative Northern Whigs, Democrats, and Know Nothings now joined the fight. Antislavery meetings and rallies surged in attendance. Black abolitionists organized a meeting at Boston’s Twelfth Baptist Church where they joined in prayer for Sumner and decried the attack on ‘our senator’ as a ‘dastardly attempt to crush out free speech.’ The caning of Charles Sumner drove home for many Americans just how much politics had changed in the nineteenth century. The crime against Sumner exposed deep divisions within the country and proved how far slaveholders would go to silence their critics and defend their property in human beings. Historian William E. Gienapp saw in the attack a turning point in the Republican party’s development: ‘Just as the Sumner assault allowed Republicans to moderate and broaden their appeal, so it proved a powerful stimulus in driving moderates and conservatives into the Republican party.’ It was the shock to the system Northerners needed to rally around the still-young party.”

In concluding the article, Gullotta writes the “insurrectionist attack on the Capitol is part of a long history of threatened and actual violence in Congress; Yale University historian Joanne Freeman, in her recent book The Field of Blood, recounts everything from fistfights, stabbings, and duels. While members of Congress are less likely to resort to physical violence today, a brawl nearly broke out on the House floor this week during the counting of the Electoral College votes, and Lauren Boebert, a Trump-supporting freshman representative from Colorado, has reportedly inquired about carrying a firearm into the Capitol. Just as the assault on Sumner finally alarmed many contented Northerners to wake up to the dangers presented by slaveholding Southerners willing to resort to violence, this week’s mob attack of the Capitol has finally turned some Trump supporters toward recognizing—or admitting—the danger he poses to the republic. A key question remains how the base of the Republican party will respond to Wednesday’s events: Will they see it as discrediting Trump and Trumpism, or will they see it as the first shot in a conflict they expect to grow worse?”

Professor Matt Galman contributes this essay linking Clement Vallandigham and his actions to the January 6 treason. Professor Galman writes, “On May 1, 1863, Clement L. Vallandigham attended a political rally in Mount Vernon, Ohio. He created a bit of a stir. Before long, federal soldiers had arrested the recently defeated Ohio congressman. He was charged with all sorts of unpleasant, even treasonous, things. The military tribunal considered the charge that the Ohio congressman had declared ‘that the present war was a wicked, cruel, and unnecessary war, one not waged for the preservation of the Union, but for the purpose of crushing out liberty and to erect a despotism; a war for the freedom of the blacks and the enslavement of the whites.’ The court found him guilty and eventually banished him to the Confederacy. We historians care about Clement Vallandigham because he was a Democratic congressman for the first half of the Civil War, and he had been a leading opponent to the Lincoln administration and the Union war effort. We remember Vallandigham as an anti-war ‘Copperhead.’ He is our most visible version of this perhaps treasonous wartime breed. Social media of the day – political cartoons, satirical cartes de visite, cheaply reprinted song sheets, and partisan editorials – feature Vallandigham’s name and face, providing historians with precious evidence and useful illustrations. The Mount Vernon crowd was a raucous one. Vallandigham, one of various speakers, declared that he opposed the war, hated Lincoln, despised conscription, and was just an angry fellow. They cheered. Except for the few Union soldiers in plain clothes, who took notes and reported back to General Ambrose E. Burnside, the recently appointed commander of the Department of the Ohio. On January 6, 2021, another angry politician who had recently lost an election gave a speech to an excited crowd, this time in Washington, D.C. Some folks say that the speaker, Donald Trump, should be held to account for treasonous speech. At this writing I do not know if that will happen, but I do know that several people in that crowd were soon committing various federal crimes and quite a few are already arrested; one is dead. Pundits on both sides of the political aisle are wondering if the Republican Party is effectively dead, or at least permanently divided. It may be that we have an unusual situation, where current political events help us rethink a somewhat murky past, while that past sharpens our understanding of recent episodes.”

Professor Gallman continues, “Historians who write about the American Civil War commonly describe the northern Democrats as divided into two camps: War Democrats and Peace Democrats. The former generally supported Abraham Lincoln and the war effort; the latter called for an end to the military conflict. Some portion of those Peace Democrats are described as ‘Copperheads.’ In our historic memory the wartime Democratic Party is seen as essentially divided while the Republican Party of Lincoln – later restyled as the Union Party – shared core values and party coherence. That is a coherent story for the textbooks, although it is not quite on the mark. We historians are sometimes lumpers and often splitters. The impulse to split leads to some fundamental conclusions. Civil War Democrats certainly differed about whether they should cast their lot with Abraham Lincoln and the war effort. Moreover, anti-war Democrats in the Midwest and in the urban East Coast (to select just two geographic areas) thought differently about the war and their opposition to it. Things get more complex when we look hard at slave-holding Democrats in border states like Kentucky. The splitting project is really pretty simple. The North’s Civil War Democrats thought different things, or at least arrayed their core passions in different orders. But what about the impulse of the lumper? Civil War Democrats generally understood themselves as ‘conservative’ and they commonly viewed politics and politicians arrayed along an ideological – as opposed to purely partisan – spectrum. They had fundamental beliefs about the Constitution and about the appropriate power of the federal government. Those core beliefs led these Democrats to some fundamental opinions about key issues of the day, including civil liberties, conscription, federal taxation, and emancipation. They shared fundamental ideas even though they divided over how to proceed. Some were bothered by the decisions of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, but they were willing to hold their noses and back the war effort because defeating the Confederacy trumped ideological concerns about public policy. For others, the administration’s policies at some point became a bridge too far. Some of those had some kinship with the Confederacy. But for many more their ideas about the Constitution and about the relationship between the federal government and the individual states led them to conclude that Lincoln and his administration had simply gone further than they could support. In this lumping formulation, many Civil War Democrats agreed on fundamental propositions, even while they split over whether they were willing to back Lincoln and the war effort. At this point one might ask about what northern Democrats thought about slavery, race, and white supremacy. Several thoughts come to mind. Many (although not all) of these northern Democrats would have agreed that the institution of slavery was immoral, and the experience of being enslaved was truly horrible. The problem for the modern observer is that these Democrats lost little sleep over the peculiar institution. Before the war they had done their best to maintain a national political party with a strong pro-slavery southern wing. With secession they no longer had to appease firebrands to the South, but they still mouthed abstract notions about states’ rights. Some endorsed the notion that the institution of slavery was really the best for both the enslaved and their white masters. But in truth they seemed indifferent to slavery as a human condition. These Democrats did worry about a post-emancipation future where population migrations would result in black freed people moving into white northern communities. They worried about miscegenation or some form of racial amalgamation in their own states, rather than about freeing enslaved people. Yes, these Democrats were racists and they embraced notions of white supremacy long before those notions had an articulated language. Were they more racist than northern Republicans? Probably. But we should not overstate that difference. With some exceptions, mainstream northern Democrats were not celebrating slavery in their speeches or private writings, even while their newspapers sold racist tropes and pushed the fear of black migrants entering their worlds. Did Clement Vallandigham and his crowd push a treasonous agenda? I do not really think so. Vallandigham and many other northern Democrats opposed the military conflict. He thought that the war would not be won, and he had no enthusiasm for emancipation. He disliked Lincoln and believed that many of his core policies, including conscription, violated the Constitution. He also had a lot to say about the fundamental cost of the war and the citizens who bore that cost. His was a radical voice in opposition to the administration, but perhaps he was more an enemy of the war and of Lincoln than a true enemy of his nation. The lumper, then, understands that northern Democrats really agreed on quite a bit. Some were War Democrats and some were Peace Democrats. And we think of some of those Peace Democrats as ‘Copperheads.’ That is a label that some Lincoln critics proudly embraced, but we should not lose track of the fact that in many cases that label ‘Copperhead’ was applied by partisan Republicans or their editors. Historians writing about the Civil War should be cautious about calling wartime Democrats ‘Copperhead’ the same way that future historians should be careful about who in 2020 should be described as a ‘socialist.’ This brings us back to January 2021. There are pretty stark divisions within today’s Republican Party. How does today’s situation compare with the divided northern Democrats during the Civil War? The wartime Democrats differed on key issues and history labels them in distinct groups. The labels defining today’s different GOP camps are pretty clear as well. We speak of ‘Never Trumpers’ and ‘Trumpers.’ Some segment of the anti-Trump Republicans have abandoned their party, if not the ideological convictions that originally made them Republicans. During the Civil War conservative editor Chauncey Burr liked to point out that he was an ideologically pure Democrat, whereas politicians who claimed to be War Democrats had really abandoned their party. Today an outspoken cohort of conservative Republicans and ex-Republicans, including the clever and caustic members of the Lincoln Project, blame the Trump Republicans for having abandoned them. The Civil War Democrats divided over whether to support a huge civil war while today’s Republicans seem to have divided over how much they support one man. Despite their differences, the Civil War Democrats shared key ideological convictions. It feels more challenging to summarize the ideology of today’s Republican Party. Like those Democrats, modern Republicans embrace the notion of ‘conservative’ values, although those are not always easy to identify. There have long been divisions in the GOP, with fiscal conservatives sparring with social conservatives, and a powerful wing of evangelical conservatives pursuing particular policy goals. But right now it is harder to get a handle on the party’s ideological core. In broad strokes, they seem to embrace tax cuts, but they appear unmoved by deficits. They do seem to be consistently opposed to excessive government regulations, particularly when the environment or worker safety are involved. And they like conservative judges, particularly if they might undermine abortion rights. One might reasonably turn to the 2020 Republican Platform for a clear sense of what the party stands for. But, alas, they passed on that ritual. There are other issues one might raise that have motivated individual Republicans, but it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that in 2020 the Republican Party was entirely about Donald Trump, rather than any consistent set of ideological convictions. (One need not be a professional pundit to predict that in the next few years ideological fissures will roil the Democratic Party. But ideology will likely be central.) Then there is the matter of race and ethnicity. History is quick to point out that the Civil War Democrats were a party of racists. That is a presentist term, but no doubt both the party’s leadership and its rank and file embraced massive racial prejudices. The contrarian points out that pretty much all white Civil War era Americans held a disturbing assortment of racist beliefs. That is certainly true, but it is a poor defense of the Democrats. Once freed from their party alignment with the southern slaveocracy, most northern Democrats seemed to have had little interest in either slavery or emancipation. They did worry tremendously about what might happen to an almost exclusively white northern society if hordes of freed people headed North. And their skilled propagandists played on those fears when speaking to voters. Today’s Republicans exist in an entirely different racial world for a host of reasons, many of which are related to the fact that the modern descendants of those enslaved people are part of public life, and they vote. Perhaps there are some similarities? Certainly white Americans today are still living in a world shaped by racism and an assortment of prejudices. And surely there is some reason to conclude that today’s white Republicans – like the wartime Democrats – are more inclined to embrace some of those prejudices than their partisan opponents. And, again like the Civil War Democrats, it might simply be the case that some of their leaders and members of the rank and file lose little sleep over racial inequalities. Certainly there are political approaches to public policies engaging racial and ethnic difference (immigration, voter suppression, policing, incarceration, drug laws) that future historians will likely describe as pretty unsettling if not flat out racist and xenophobic. And perhaps the gap between the parties is actually more pronounced today than in the 1860s, if only because of the racial composition of voters in each party today. Democrats worried about what would become of them if their white worlds became more racially diverse; today’s Trump Republicans surely seem to be deeply concerned about the implications of a racially and culturally diverse society. This is not intended as a screed against today’s Republican Party (well, not entirely), but rather as a call for thinking about those wartime Democrats in this broader context. They differed with each other about whether the party should support that huge war, but they really agreed on a broad spectrum of conservative ideals. And even the folks who backed Abraham Lincoln did not really embrace everything he was doing. They were, in those senses, a coherent political party. Let us return to those two speeches. On May 1, 1863, Clement Vallandigham had a lot of nasty things to say about the war and the Lincoln administration. But in recalling the congressman and his angry rhetoric, it is perhaps worth keeping in mind that he provided his audience with a clear path to addressing these national ills. The answer, he said, rests in ‘the ballot box.’ If his supporters wished to end Lincoln’s tyrannical reign they should vote him out of office. On January 6, 2021, the President of the United States spoke to an enthusiastic crowd in Washington. His core message was a bald-faced lie. He declared, not for the first or last time, that he had been cheated in the 2020 election. History will judge whether he was fully conscious of the fact that he was lying. In any case, the enthusiasts in that crowd believed everything he said. And whereas Clement Vallandigham – the man we recall as a traitor to his country – urged his listeners to use the ballot box to end the war, Donald Trump urged his listeners to march to the United States Capitol, where they might stop the constitutionally determined process of counting votes from the Electoral College. In the short run they were astonishingly successful, aided by a shocking number of elected leaders from the Republican Party. In late 1863 Vallandigham lost another election when Ohioans turned back his bid for the governorship, preferring John Brough, a War Democrat. There is apparently no record of the loser declaring that he had been cheated. Say what you want about the wartime Democrats, but they revered the Constitution. Vallandigham faced a military tribunal for his Mount Vernon speech. It remains to be seen what Donald Trump will face.”

Next we look at this article bringing in Reconstruction, which won’t be the last time. It’s an interview with Professor Eric Foner. Professor Foner says, “Well, I guess the sight of people storming the Capitol and carrying Confederate flags with them makes it impossible not to think about American history. That was an unprecedented display. But in a larger sense, yes, the events we saw reminded me very much of the Reconstruction era and the overthrow of Reconstruction, which was often accompanied, or accomplished, I should say, by violent assaults on elected officials. There were incidents then where elected, biracial governments were overthrown by mobs, by coup d’états, by various forms of violent terrorism. There was the Colfax Massacre, in 1873, in Louisiana, where armed whites murdered dozens of members of a Black militia and took control of Grant Parish. Or you can go further into the nineteenth century, to the Wilmington riot of 1898, in North Carolina. Again, a democratically elected, biracial local government was ousted by a violent assault by armed whites. They took over the city. It also reminded me of what they call the Battle of Liberty Place, which took place in New Orleans, in 1874, when the White League—they had the courage of their convictions then, they called themselves what they wanted people to know—had an uprising against the biracial government of Louisiana that was eventually put down by federal forces. So it’s not unprecedented that violent racists try to overturn democratic elections.”

In discussing the rhetoric at that time compared to January 6, Professor Foner makes this point: “It was straight white supremacy. Maybe one might say there were two different tacks. One was to say that the Reconstruction government was corrupt or dishonest or their taxes were too high, things like that. That was meant to appeal to the North to not intervene, and say that these people were trying to restore good government in the South. But mostly it was straight-out white supremacy: Let the white man rule, this is a white Republic. I mean, racism was totally blatant back then. Today, they talk about dog whistles or other circumlocutions, but back then, no, it was just that armed whites in the South could not accept the idea of African-Americans as fellow-citizens or their votes as being legitimate. It also reminds me of when President Trump first launched his political career and was pushing the idea that Obama was not really an American and, therefore, could not be president. And the idea that Black people are actually aliens in a certain way—that they are not truly American, that the only true Americans are whites—that’s been around for a long time in our history. And it does link what we saw the other day to Reconstruction and the battles over that.”

Professor Foner has this comment on the symbolism of the flags the mob carried. “It was also that there were people carrying these American Revolution flags, ‘Don’t tread on me,’ that sort of thing. So they identified themselves with the Confederacy, obviously, with their flags. They also identified themselves with the Patriots of 1776. After all, the United States was founded by a revolution that overthrew the existing authority, the British. But, last week, these were fantasy revolutionaries. They weren’t really in a position to overturn the government, but they were trying to put themselves in the tradition of the people who overturned British rule here.” Linking this with the confederacy, Professor Foner said, “Well, the Confederates claimed to be in the tradition of the American Revolution. After all, the Declaration of Independence says that the people have a right to alter or overthrow the government if they don’t like it. They said, ‘We are in the tradition of 1776.’ Of course, they also rejected another famous part of the Declaration of Independence, the idea that all men are created equal. That did not appeal to them very much. Alexander Stephens, the Vice-President of the Confederacy, very famously gave a speech saying that white supremacy is the cornerstone of the Confederacy—that Negroes, as he put it, that their natural state is being a slave. According to Stephens and most other Confederates, they certainly were not equal to white people. So this is a racialized view of the right to resistance in American history. It excludes African-Americans, but it includes these violent white people.”

Professor Foner discusses the mistakes in teaching Reconstruction history. “First of all, I think how we think about history is very important. So, as a historian, I do believe that strongly. The mythology, I’d have to say, about Reconstruction was not just a question of teaching it wrongly. It was an ideological part of the notion of the Lost Cause, that Reconstruction was a vindictive effort by Northerners to punish white Southerners, that Black people were incapable of taking part intelligently in a democratic government. And therefore, the overthrow of Reconstruction was legitimate, according to this view. It was correct because those governments were so bad. This was part of the intellectual edifice of the Jim Crow system, that if you gave the right to vote back to Black people—and it had been taken away by the turn of the century—you would have the horrors of Reconstruction again. This image of Reconstruction, as the lowest point in the saga of American history, was very much a vindication and a legitimation of the Jim Crow system in the South, which lasted from the eighteen-nineties down into the nineteen-sixties. So history was part of that legitimation. The motto of the historian is generally, ‘It’s too soon to tell.’ But I do think eventually people will have to see January 6th, I hope will see it, as really a very serious violation of the norms of democratic government. It was not a fly-by-night operation. It was not a misguided group who got a little out of hand or something like that. It was really an attempt to completely subvert the democratic process by violence. And I think that the lesson, if we want to get a lesson out of it, is the fragility of democratic culture. I don’t know how many there were, but the thousands who stormed the Capitol do not believe in political democracy when they lose. They believe in it when they win, but that’s not democracy. So I think we have to be aware of this strand in our history, which is perhaps, what can I say, less worthy than the strands we tend to talk about more, the notion of equality, the notion of opportunity, the notion of liberty, democracy. You get a lot of talk about that in our history classes. You don’t get a lot of talk about the antidemocratic strands in American history, which have always been with us. And this is an exemplification of it. So I think January 6th was an interesting day from a historical point of view, because it began, if you remember, with people talking about the victory of these two candidates in Georgia, a Black man and a Jewish man, and realizing that’s an amazing thing for Georgia. Georgia has a very long history of racism and anti-Semitism. That’s how it began. Four or six hours later, you have an armed mob seizing the Capitol building. You have these two themes of American history in juxtaposition to each other. That’s my point. And both of them are part of the American tradition, and we have to be aware of both of them, not just the more honorable parts.”

Professor Foner gets asked what Reconstruction lessons can tell us about Republicans today calling for “unity” by not holding Trump accountable. “I think the lesson of Reconstruction, sadly, is that it requires a lot of vigor, I suppose, to actually enforce a kind of a new regime. Reconstruction in our modern terminology was an attempt at regime change. Remember how we used to talk about regime change in Iraq and that kind of thing? Changing a regime based on slavery to one based on racial equality, that was a pretty big job to do. And it required force. President Grant was elected in 1868 with the slogan, ‘Let us have peace.’ He wanted reconciliation. Three years later, he’s sending troops into South Carolina to crush the Ku Klux Klan. You can’t have peace when the other side is out there acting as a terrorist body, assassinating people if they try to vote and things like that. So the tragedy of Reconstruction is that the commitment to enforce it waned much too soon. It was a national problem, not just a Southern one. And eventually, with the acquiescence of the North, with the acquiescence of the Supreme Court, you get the overthrow of this ideal of equality and the imposition of a new system of white supremacy. It’s not the same as slavery, it’s different, but it’s still a deeply unequal system in the South that then lasts well into the middle of the twentieth century. So, yeah, reconciliation is a wonderful idea, but it takes two to tango. And if Southern whites were irreconcilable, that made it very difficult.”

He concludes, “Georgia, like much of the Deep South, had a long history, first of all, of slavery. It was one of the major cotton-producing slave states. In Reconstruction, it had a very active Klan, which was very brutal and violent toward African-Americans and toward whites who coöperated with them. Later, it disenfranchised Black voters for a long time. In the middle of the twentieth century, you have leaders like Herman Talmadge there who were just absolute outright racist. You also have the lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory superintendent in Georgia in the early twentieth century. So anti-Semitism was also pretty well entrenched. I’m giving you a litany of bad things, but what’s actually important is that people are able to overcome this. That with that history hanging over you, you still can elect a Black man and a Jew to the Senate from Georgia. So I think that’s cause for optimism. We teach history, but history is not determinism. We don’t have to just relive our history over and over again. It’s possible to move beyond it, and I think what happened in Georgia is a little step in that direction.”

This article also brings in Reconstruction. This article contains an interview with Professor Cynthia Nicoletti. Professor Nicoletti says, “After the war, Northerners were talking about things like, Let’s hang Jeff Davis from the sour apple tree. There was this rumor that Davis was arrested wearing women’s clothing—that by all accounts was not actually true, and he was very angry about it!—and that led to people saying, Let’s take him, put him in women’s clothing, parade him through the streets, and charge people to see him humiliated. But the American justice system doesn’t work like that—and so one of the things that really interested me is how difficult getting the ‘right’ outcome was. One of the things that’s really important here is that the government was all gung-ho to put Davis on trial for treason at the end of the war. There was a fervor to try him—like, If we don’t, what we’re suggesting is that waging this war, on this huge scale, and killing all these people for this terrible cause will go unpunished. We are not a nation if we are not capable of trying the head traitor for treason. They could have tried all the Confederates for treason, but they thought, Let’s have Davis be the first test case, and after he’s tried and convicted, there will be lots of prosecutions to follow. But it quickly became apparent that they could get the wrong outcome in the trial, and they worry that if the Davis trial is supposed to be a proxy for the idea that the Confederate war effort was illegal—that states were not allowed to secede from the Union—what happens if they get the wrong outcome? If they get a jury that refuses to convict Davis, what does that say about the legality of the war effort? What if they get a judge, or even a Supreme Court justice, who says something like Secession was legitimate? There was also a real debate within Northern society about punishing these people, versus showing them mercy. What’s interesting is how quickly this really intense sentiment—we should hang all of the Confederates, and make all of them pay—Vengeance!—really fades. Public opinion did really change quite dramatically. Reading newspapers and people’s letters, you see Northerners very fired up about punishing Confederates through 1865, and when you get to 1866, it starts to dissipate. The question really is, how would you punish Confederates? If you’re going to punish them through the legal system, and in a way that really comports with the letter of law and all of the protections the United States Constitution affords to all criminal defendants, it makes it hard to try them and make sure you get a conviction. I think public opinion is in some sense related to this, because it becomes clear that exactly what the outcome is going to look like is not going to be fully satisfying to Northerners.”

Professor Nicoletti answers a question about how the argument regarding not punishing Jefferson Davis developed. She says, “The real problem was Northerners have to rebuild a society in which Southerners are a part. To what extent are they going to be outcast forever? There was also the problem of violence emerging again. I think today this sounds ridiculous to us, but at the time, the prospect of another civil war got talked about a lot. They think, as soon as Southerners get some arms together, they might rebel again. … The founding of the Ku Klux Klan in late 1865, and the violence in Southern cities in 1866 [see: Norfolk, Virginia; New Orleans; Memphis, Tennessee], looked like it might be the sign of something even more serious. In hindsight, it’s easy to track momentum in one direction or another, but if you’re living through it, it’s hard to see. And on the flip side, there was also this sense of, We’re all Americans, and we have the legacy of the Revolution, and how do we knit this thing back together? I think today this sentiment seems very foreign to us. … Why didn’t we show no mercy? And that is a very hard question for them, as well. They’re thinking—to what extent are they going to crush all of Southern society? If you can get over the pain of doing that and having a generation of the Southern economy totally decimated, would we have come out different and maybe better on the other end? But they’d be paying the price in the immediate short term. That price was immediately palpable to them, in a way that’s not palpable to us. They’re thinking, How do we put this back together without an endless series of wars? And they’re honestly quite worn out. There’s also a big class question here, which is—white elite Southerners were already trying to re-form their old friendships with white elite Northerners. It’s sort of amazing, the degree to which some elite white Southerners get back in the good graces of those Northern friends. And the Southern elite would often say things [about the violence] like, Well, you know, we can’t keep the masses in check. And related to that class point, there’s also a dynamic happening here, which is that Northerners are wondering—how much of a revolution is this going to be? How far do we want to go? The radicals wanted to go quite far, and wrote these new Constitutional amendments that are quite radical for the time—actually, not even just for the time! They’re still radical now. They were guaranteeing racial equality for the very first time, and that’s part of American law now. And people are thinking, How much farther are we going to push that? Are we going to totally upend Southern society, do things like land redistribution, break up plantations, give land to not just Black people but poor white people? These ideas get debated, but Americans—and I mean Northerners as well as Southerners—are fundamentally conservative with a small c. I don’t think they could really imagine totally reimagining the world, starting from scratch. I spent a lot of time looking at the attorney general of the United States [Henry Stanbery], whose job it was to bring prosecutions against Confederates, who was supposed to order the various U.S. attorneys to bring prosecutions. And they think about going with military tribunals, and other kinds of ways where they could make sure the jury doesn’t have any former Confederates on it, but Stanbery was very against this. And behind his belief that they shouldn’t do this was this sense of, We have to bring the country back to normal; we’ve been in a state of chaos, where we’ve suspended lots of rules that normally apply, but our constitutional system has to go back to normal.“

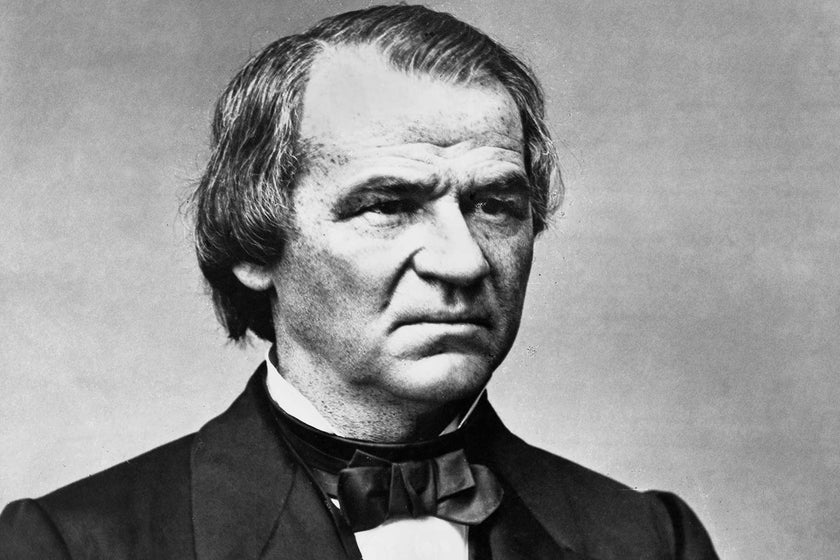

When asked about Andrew Johnson’s leniency in pardoning all confederates, she says, “In studying just the issue of treason, I have a bit more sympathy for Johnson than I think many historians who look more broadly at him do, because he was really caught in a bind. There’s an apocryphal story that Lincoln said, before he died, as Davis was escaping and fleeing South, that Lincoln hoped Davis might get away to Mexico. That this was the best option, because then they wouldn’t have to deal with the problem of trying him. I think Johnson, in reflecting on that idea, eventually comes to the realization that Lincoln was right. Davis’ trial just becomes this huge political liability for him. At first, Johnson was very strong on the idea of trying Confederates for treason; he was the one Southerner who refused to leave Congress when his state seceded, and he was a populist, working class, had taken it on the chin from these elite slaveholders his whole life. So at first, he was gung-ho on the idea. Then when his Cabinet started meeting and his attorney general raised these concerns, Johnson had time to repent this impulse at great length. It became a political weapon in the hands of his enemies. There was an unsuccessful initial attempt to impeach him [in 1867] that investigated the question as to why he didn’t try Davis, suggesting he was failing to do so because he was sympathetic to Confederates. But everyone involved in the trial testified before the House and said no, there were very good reasons why not. I think the blame that’s to be laid at Johnson’s door is less about the Davis pardon, and more the fact that he gave amnesty, en masse, to basically everybody, in May 1865. Except for the higher-ups—14 groups of people, including those who had held Confederate offices or who had more than $20,000 in property—who had to apply for individual pardons by applying personally. But then, over the course of 1865, he granted almost all of those. He might have issued conditional pardons—things like, you get a pardon if you transfer some of your land to the people you enslaved—but he didn’t.”

In this article the author starts wih Joe Biden sayin, “Let me be very clear, the scenes of chaos at the Capitol do not reflect a true America, do not represent who we are.” The article continues, “This is how we expect politicians from both major parties to talk when vicious, hateful rhetoric incites mass violence. In March 1861, after seven slave states had already left the Union, Abraham Lincoln, the only president revered today by both elite Democrats and Republicans, tried to soothe the rebels who were arming for war. ‘We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies,’ he told them in his first inaugural address. ‘Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.’ At the end he famously appealed to the ‘better angels of our nature.’ The mob of Trumpers that smashed its way into the Capitol yesterday should serve as a rebuke to such willful innocence. The rioters inflamed by the endless lies and racist conspiracy theories spouted from the White House are just the latest in an unbroken tradition that is as truly American as the people of all races who have struggled for a tolerant, egalitarian, and democratic nation. One cannot honor the latter without coming to grips with the people they fought against. In 1857, President James Buchanan endorsed a state constitution to protect slavery in Kansas that a minority of white settlers there had drafted after several years of bloody conflict. In 1863, the governor of New York, Horatio Seymour, addressed as ‘my friends’ a crowd of white boys and men who had been protesting the Civil War draft by burning down buildings and lynching Black people on the streets of Manhattan. While bemoaning the violence, the city’s leading Democratic paper asked rhetorically, ‘Does any man wonder that poor men refuse to be forced into a war . . . perverted almost into partisanship.’ During Reconstruction, Seymour and other leading politicians from his party looked the other way or actively abetted the Ku Klux Klan as it went about terrorizing Black voters and battling the Union troops dispatched to protect them. The revived KKK of the 1920s, which was a scourge to Catholics and Jews as well as African Americans, took over the Republican Party in several Northern states and counties. And Democrats, at their 1924 convention, narrowly defeated a resolution to condemn the violent group whose membership then numbered close to 4 million. The history of modern American conservatism is strewn with similar examples of bigoted movements that got help from authorities, political and otherwise. There were the police captains and clergymen who promoted the anti-Semitic populist ravings of Father Charles Coughlin during the Great Depression and the White Citizens Councils, full of businessmen and professionals, who led resistance to the Black freedom movement in the South during the 1950s and 1960s. Barry Goldwater won the 1964 GOP presidential nomination thanks in part to grassroots campaigning by the John Birch Society, whose founder had accused President Dwight Eisenhower of being ‘a dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy.’ After decades in decline, the JBS sprang back to life when Trump got elected in 2016. The Texas chapter quickly doubled its membership, signed up a number of legislators, and became vocal backers of such powerful right-wing politicians as Senator Ted Cruz and Representative Louie Gohmert. Most of the Republicans now mouthing predictable words of censure about the riot are careful to say nothing that would turn the mass of pro-Trumpers against them. A snap poll taken by YouGov found that nearly half of all GOP voters supported the actions of those at the Capitol. And when the president who urged them to storm the building called into a meeting of the Republican National Committee today, he was greeted by what the Washington Post called ‘a loud and overwhelmingly enthusiastic reception.’ This atrocious national tradition will likely endure years after Trump has retreated to his resort in Florida and his followers have found other leaders and movements to stoke their fear and anger. Sweet talk about ‘unity’ and our ‘better angels’ did not defeat them before and will not now. Confront them with the truth, block them in the legislatures and the executive suites and the courts, protest them in the streets, and crush them at the polls.”

In this article we have another interview with Professor Foner. He’s asked about politicians quoting Abraham Lincoln in the wake of the January 6 treason, especially Republican Whip Steve Scalise quoting from Lincoln’s Second Inaural, “With malice toward none, with charity for all, let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds.” He responds, “Well, primarily, it tells me that you really can’t go wrong by quoting Abraham Lincoln. However, before Lincoln spoke about healing up the nation’s wounds – malice toward none, charity toward all – he also said that this war, the Civil War, was God’s punishment on the nation for the evil of slavery and, that if it was necessary, to have every drop of blood drawn by the lash repaid by one drawn by the sword – that’s Lincoln’s words – that would still be justice. In other words, what Lincoln is saying is reconciliation needs justice to come with it. Reconciliation needs accountability. You can’t just wash your hands and say, let’s forget about the past and move forward with healing. … You know, after this speech about reconciliation, President Lincoln was assassinated a month later by a strong Confederate sympathizer. In other words, reconciliation requires two to tango. And unfortunately, in the Civil War, and particularly in the aftermath of the war in the Reconstruction era, large numbers of white southerners were not willing to accept the freed slaves as fellow citizens. They launched a campaign of violence, the Ku Klux Klan and terrorist groups like that, just as we saw the other day, willing to use violence to try to overturn democratically elected biracial governments.” He also says, “Well, reconciliation came eventually, but there was a high cost to that. The cost was, A, ignoring what the Civil War was about, that slavery was sort of erased from the memory of the war. And secondly, Black people were not part of this reconciliation. It meant accepting the southern racial system that was put in place that we call Jim Crow. So in other words, it was a white reconciliation.”

Professor Foner is asked, “A lot of Republicans were saying this week that impeachment would only interfere with national healing, with reconciliation. Do you believe that time has told us that accountability and unity are mutually exclusive?” He answers, “Well, I mean, you know, you have a political party that has been emphasizing law and order a lot during this presidential campaign. You know, law and order seems to require that if people commit crimes of one kind or another, they ought to be punished. Impeachment is the way you punish a president. The division is here. The question is, how do you deal with people who violated the law and further exacerbated the division?” He ends by talking about what unity is, at the bottom line. He says, “Well, unity, it does not mean that everybody thinks the same or has exactly the same political outlook. Unity here would mean that people are committed to the democratic process. So, you know, those who call for unity in this case seem to be those who just want to forget about the past. And I don’t think that’s really the path to unity.”

This article is based on an interview with Professor David Blight. ” ‘We really have arrived at, it appears, two irreconcilable Americas with their own information systems, their own facts, their own story, their own narrative,’ says David Blight, the legendary Yale historian whose work studying the Civil War and Reconstruction Era won him a Pulitzer Prize. The threat he sees isn’t that there will be another literal war: It’s the threat of two rival stories about America taking root, as they did after the Civil War. One of them, a heroic ‘Lost Cause’ narrative of a noble Confederacy whose soldiers sacrificed themselves for honor and tradition, flourished for decades, justifying the fight for slavery and continuing to distort American politics to this day. As Donald Trump’s more extremist followers cling to his bogus claims of a stolen election, wrapping Trump’s complaints into a nationalist counternarrative driven by racial anxiety and anger at the government, they risk creating a legacy that will divide the country long after the man himself leaves the stage. ‘In search of a story—in search of a history, in search of a leader, in search of anything they can attach to—lost causes tend to become these great mythologies whose great conspiracy theories tend to explain everything,’ says Blight. Witness, for instance, the bizarre staying power of QAnon—the baseless pro-Trump conspiracy theory that imagined Trump would remain in power after January 20 as he fought off a cabal of Satanic pedophiles who secretly control the government. January 20 came and went. Joe Biden was sworn in. And while some QAnon devotees found themselves humiliated and questioning their beliefs, others doubled down, moving the goal posts—it’s all part of the plan, just wait and see. ‘At the heart of a lost cause, if it has staying power, is its capacity to turn itself into a victory story,’ says Blight. ‘Can Trumpism ultimately convert itself into some kind of victory story? We don’t know that yet.’ Especially in the wake of the January 6 insurrection, cries for unity have been heard throughout Washington, as the need to come together feels more urgent than it has in years. Here, Blight sees a useful lesson to be found in history: ‘In all the work I’ve done on the Civil War and public memory, the central thing I’ve learned is that you can’t have healing without some balance with justice,’ says Blight. ‘You have to have both. The justice has to be just as real as any kind of healing.’ “

Asked if 2020 and 2021 reminded him of 1860 and 1861, Professor Blight responds, “I’ve been asked many times in the past two weeks which other election, which other inauguration we can compare it to. And really the only one is 1861. Lincoln faced seven seceded states and the formal inauguration of Jefferson Davis [as president of the Confederacy]. So, you know, a pretty horrible situation. Biden is inheriting something different, but comparable. We really have arrived at, it appears, two irreconcilable Americas with their own information systems, their own facts, their own story, their own narrative. And we — whatever ‘we’ is — on the other side keep wondering: How can this be? We’re drawn back to the Civil War because its great issues—especially the great issues of Reconstruction—are still with us: the nature of federalism; the relationship between the states and the federal government; what government means in people’s lives; how centralized government should be; how energetic, how interventionist government should be; and race and racism. The Civil War and Reconstruction are the country’s first great racial reckoning, and it brought about tremendous changes in law and in life—and then, of course, it brought about a counterrevolution that defeated much of it.”

Comparing Trump’s “stolen election” lie to the lost cause lie, Professor Blight says, “It’s very similar to the Confederate Lost Cause, and, to some extent, even what gave rise to the Nazis in the 1920s: the German ‘Lost Cause,’ the ‘stab in the back’ theory of World War I [the belief that the Germans didn’t lose the war, but were instead betrayed from within].They have a set of passionate beliefs—not facts, passionate beliefs. In search of a story—in search of a history, in search of a leader, in search of anything they can attach to—lost causes tend to become these great mythologies whose great conspiracy theories tend to explain everything. Lost causes are careful and organized in knowing what they hate. They know what the enemy is or was, and they manufacture these stories that explain almost everything that has happened to a people who are aggrieved. But I can’t even begin to understand something like the QAnon conspiracy, which seems beyond the pale of any kind of organized grievance. A lot of the analysis of Trumpism is that these people were harboring all kinds of grievances for a long time—about their economic condition, about their sense of displacement in American society, about loss of status, and so on. There is a lot of reality in that that a lot of us liberals and academics don’t always want to face. The Confederate Lost Cause was rooted in some real things: a colossal defeat and tremendous loss—probably 300,000 white Southerners perished in that war—and destruction of their land and economy. It was a collective psychological response to mass trauma. The Trumpian Lost Cause is, at its core, a set of beliefs in search of a history and a story. The question is, how long do these beliefs survive? The stolen election is the biggest of their beliefs, but they’ve got a lot of others: the liberals are coming for your guns, and liberals are coming for your taxes, and the liberals want to plow all your tax money into those cities for the black and brown people, and liberals are going to open up the border and continue this browning of America, and liberals are running the universities and taking them to hell in a hand basket, and so on. Trumpism has the ingredients for this. It may depend on how much of a ‘victim’ he becomes. If he’s really victimized, in their view, by the impeachment trial or by prosecutions—if he goes to jail for two years, like Jefferson Davis did—God help us. He could come out the victimized saint of that Lost Cause. Even if it dwindles down to only a few million people, they could be extremely dangerous. At the heart of a lost cause, if it has staying power, is its capacity to turn itself into a victory story. The Confederate Lost Cause really did that: By the 1890s, it became the story of victory over Reconstruction. The Germans did something very similar with the ‘stab in the back’ and the whole ‘Jewish conspiracy’ story: They turned it into a victory over corruption, over communism and over Jews and everything. Can Trumpism ultimately convert itself into some kind of victory story? We don’t know that yet.”

Asked about the odious Tucker Carlson telling his audience of zombies that what Democrats want is “a new Reconstruction,” Professor Blight says, “Well, they must be drawing on this idea of the ‘Yankee colonization of the South,’ the remaking of their schools, the remaking of their economy, the forced politicization of the freed Black population in very narrow corners of the South for a very short period of time, and some land and property redistribution. They must be drawing on that fear of pushing great change on people either before they’re ready for it or forcing a change that should never be done anyway. That deep myth—that somehow if Reconstruction just hadn’t been pushed so fast, the country would have healed and there wouldn’t have been all that violence, and the country would have gotten along better if you didn’t have government imposing itself on people—it’s that idea that the federal government is always waiting to become the giant leviathan that’s going to take over your lives, your schools, churches, homes, your habits and your values. One of the great successes of the modern conservative movement, especially since Reagan, is that they have made a huge swath of this country essentially hate government, fear government, detest government. And I’ve always felt like it’s also been a mistake of the Democrats to not fight back on that one harder than they are.”

In this article we have yet another interview with Professor Eric Foner. We learn, “The mob, under the spell of fabrications about the presidential election being stolen — especially in states with high Black populations — sought to ‘take back the country’ through violence. The scene, just one day after Democrats secured control of Congress through the election of a Black senator and a Jewish senator in Georgia, mirrored coup attempts from the Reconstruction era. Reconstruction, the period following the Civil War, from 1863 to 1877, tried to redress the inequities of slavery by giving rights to Black people through the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. It attempted to rebuild the South’s economy and empower Black people by abolishing slavery, granting them the right to vote, promising equal protections, expanding education and civil rights, and instituting biracial governments, where Black political leaders sat alongside white ones. But since a sector of white America opposed this — vestiges of the Confederacy attempting to stay alive — white mobs took it upon themselves to push back against progress by killing the people who tried to move forward. The push and pull between Black advancement and white supremacy then mirrors the forces at play today.”

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22250056/GettyImages_2111589.jpg)

MPI/Getty Images

Asked if he saw parallels between the January 6 treason and Reconstruction, Professor Foner says, “My thoughts turned to Reconstruction when I saw the mob attacking the Capitol, and particularly because many of the TV commentators were saying this is unprecedented, that this is something new in American history. It was unprecedented in terms of storming the Capitol itself. But in terms of violent mobs trying to overturn a democratic election, that it was not unprecedented at all. This happened many times in the Reconstruction era and just after that era. … If you go back to Reconstruction, there are a couple of examples. In the Colfax massacre of 1873 in Louisiana, whites overran the county courthouse, killed a whole bunch of Black militiamen, and basically took over the local government even though Republicans had won. It was a biracial government. Jump all the way up to 1898 to the Wilmington riot, when a biracial elected government of Wilmington, North Carolina, was ousted in a kind of coup d’état by armed whites. They were driven from the city and a new government took over. In 1874 in New Orleans, which was the capital at the time, a group called the White League — they were pretty explicit about what they stood for — had an uprising where they tried to seize the government of Louisiana. US troops had to come in to put them down. So, in other words, we’ve seen this before. While we like to talk about ourselves as the world’s oldest democracy, as a democratic culture, there’s also a powerful strand of anti-democratic feeling in the United States, especially when it comes to race and the role of African Americans. For many decades, Black people couldn’t even vote in the South up until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. There’s this distrust of actual democracy, especially if your side doesn’t win. As I say, I think there certainly are parallels to Reconstruction and the overthrow of Reconstruction.”

Expanding on Reconstruction actions, Professor Foner says the white mobs of the time acted, “To restore white supremacy. It’s as simple as that. In Reconstruction, for the first time in American history, the laws and the Constitution were being written and Black people were recognized as citizens in the United States. They were given — men, anyway — the right to vote and hold office. By the later part of the 1860s and into the 1870s, there were these biracial governments functioning in the South. This was something that white supremacy found impossible to accept. You’re talking about five to six years after the end of slavery here, and yet now, African Americans are actually exercising significant political power. These uprisings were an attempt to restore white supremacy and they were pretty explicit about it.”

Moving to the January 6 treason, Professor Foner adds, “It’s hard to know exactly what the practical purpose of the mob was on January 6. Okay, they stormed the Capitol, but how could doing so actually overturn the election? In Reconstruction, they just killed or drove out officeholders. With this group, maybe they were planning to kill or drive out Congress and prevent it from actually certifying the electoral votes that made Biden the president-elect. It’s hard to know. I’m not even sure they thought this through logically; they knew they wanted to somehow stand up to the absurd charge that Trump won the vote in a landslide and was somehow deprived of election. When they got in there, some of them were extremely violent and some of them were just walking around taking selfies, which is not likely to overturn the government. The violence of Reconstruction was far more pervasive than what we saw the other day. Nobody knows how many, but maybe [2,000] or 3,000 African Americans were killed in Reconstruction by the Klan and by all these white supremacist groups committing acts of violence. And many of these killings were not related to elections, necessarily. Black schoolhouses were burned and teachers assaulted; a Black farmer who got into a dispute with a landlord would be assaulted by the Klan. They were trying to restore white supremacy in all features and aspects of life. But, of course, political power was one very important part of that.”

Moving on to Andrew Johnson, Professor Foner says, “I’m sure that Trump knows nothing about Andrew Johnson, historically. But, no doubt, he’s aware that Johnson was impeached. And if you go back, Johnson was a precursor to Trump in some ways. He used crazy, extreme language. He denounced the Republicans in Congress as murderers. He accused them of plotting the assassination of Lincoln. He didn’t have Facebook or Twitter to spread his views, but in speeches and other things, he used the most extreme kind of lunatic language like Trump. He encouraged people to break the law. He said the Reconstruction laws that were passed by Congress weren’t real laws that need to be obeyed. He seems to have encouraged violence. He absolutely stood up for white supremacy. Trump launched his political career by claiming that President Obama was not really an American citizen. Johnson, 150 years earlier, vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 because it made Black people citizens. He said Black people should not be citizens, that they’re incapable and intellectually unable to be citizens of the United States. I’m sure Trump never read Johnson’s veto message, but that same theme is there in Trumpism and in Johnson’s opposition to Reconstruction.”

This article, as well, takes us to Reconstruction for guidance, context, and lessons. We learn, “During Reconstruction, a raft of attempted insurrections flared up across the former Confederacy. Violent storms of white supremacists rocked swaths of the South, all aimed at undoing the Union’s victory during the Civil War, as well as the civil rights gains made thereafter. Racial equality, civil rights protections, basic recognition of democratic outcomes — all were targets of rampaging white terrorists, using violence to launch themselves to power once more. Numbers are hazy, but dozens perished as a direct result of insurrection, part of the thousands of victims of white supremacist political violence during the era. ‘What occurred in the South in the late 1860s and the 1870s was at a scope and scale of violence and resistance that was not even remotely similar to what we saw [in Washington],’ Mark Pitcavage, a historian and senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League, told me. The scale of violence ‘was so big that there are some people who say it was a low-intensity conflict. I don’t know if I want to go all the way there, but parts of it weren’t too far off from that.’ However, the echoes of that Reconstruction-era violence — led by both white marauders (cloaked as the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist groups) and white supremacist Democratic officials bent on reclaiming power from Republicans — were impossible to escape in Washington in early January when the rioters paraded Confederate flags through the halls of the Capitol and chanted threats to hang the vice president. Though largely overlooked in mainstream American history, these insurrections — in Louisiana, in South Carolina, in Mississippi, in North Carolina — attempted to install terrorist-backed regimes in multiple post-Confederacy states. Their longevity was echoed as well in the warning last week from the Department of Homeland Security, which said for the first time publicly that the country faced a rising threat from “violent domestic extremists” who sympathized with the Capitol attack and the false narrative, stoked by former President Donald Trump, that the election was rigged. ‘We have to realize that this is a powerful strand in the American experience. It’s always been here, the resistance to actual democracy,’ Eric Foner, a historian at Columbia University who specializes on Reconstruction, told me. ‘We pride ourselves on being a democracy, but there’s actually a long tradition of people who don’t think that, who are unwilling to accept the rights of African-Americans to be citizens, the right of elections to overturn governments in power. In other words, we should realize the fragility of democratic culture.’ While that fragility was on full display in the aftermath of the Civil War (as well as during the siege on the Capitol), those Reconstruction-era insurrectionists contended with a force they consistently underestimated: Ulysses S. Grant, who served as president from 1868-76. Rising to the presidency as the heroic general of the Civil War, Grant entered the White House amidst violent white extremists continuing to roil American politics — and following the failed presidency of a one-term impeached president, who had only added fuel to the post-war inferno. Time and again, Grant battled back, sometimes almost single-handedly, against rising insurrections bursting across the South. Time and again, he appeared to succeed — only to eventually watch the entire edifice of Reconstruction crumble under Supreme Court decisions, wilting willingness among Northern whites to win the peace, and, most especially, a Compromise of 1877 that cemented the beginnings of the Jim Crow era to come. Grant’s approach relied on a combination of brute military force and a drastic curtailment of civil liberties, yet it nevertheless has relevance for the current moment and contains lessons for lawmakers who fear that January 6 might have been only the first of widespread attacks on the government and elected officials at all levels, across large swaths of the nation. Officials in our current era have many more legal tools at their disposal to combat such terrorism. But as Grant’s experience shows, it’s not just the tools that count; rather, it’s the willingness to persist in the fight that will likely decide whether these counter-terrorism efforts actually succeed.”

The article continues, “By the time Grant ascended to the presidency, insurrection was already in the air across the post-Confederacy South. ‘Originally, white supremacist terrorism was aimed at individuals, African-Americans, white allies, sometimes military occupying forces,’ Brooks Simpson, an American historian at Arizona State University, told me. ‘By 1868 that had become more systematic in terms of not only going after voters, but also state legislators.’ Massacres targeting Black freedmen and their white allies occurred with regularity, led by newly formed terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Not all of it was technically insurrectionist, per se. For instance, Louisiana’s Colfax Massacre — the ‘bloodiest act of racial violence in all of Reconstruction,’ Grant biographer Jean Smith wrote — came from white Louisianans’ refusal to accept the 1872 election, though wasn’t necessarily aimed directly at overthrowing the state government (at least immediately). But it wasn’t far into Grant’s tenure when the marriage of white terror and disaffected Confederates proved lethal to the administration’s Reconstructionist efforts. And in North Carolina in 1870, they struck first political blood: Ku Klux Klan terror ‘helped the Democrats recapture the state, electing five of seven congressmen,’ Smith wrote. Amidst the white terror campaigns, Grant and his legislative allies spied a solution. That year, Congress passed the first of what eventually would become three Enforcement Acts. In effect, the statutes made it a federal offense to deprive individuals of civil or political rights, and provided greater federal oversight of elections and voter registration. That wasn’t all. A few weeks later Congress voted to create the Department of Justice, staffing up lawyers under the attorney general and giving the attorney general oversight of all U.S. attorneys and federal marshals. Grant took full advantage of the new tools, putting a ‘powerful team’ together to head the Justice Department, wrote Smith. New Attorney General Amos Akerman understood the stakes, saying that the Klan was in effect leading a ‘war, and cannot be effectively crushed on any other theory.’ With white supremacist terror continuing to race across the region, led primarily by the Klan, Grant decided to make countering the terrorists his sole focus. In March 1871, he requested a special legislative session for the express purpose of suppressing the group, whose thousands of members across the South formed a so-called ‘Invisible Empire.’ The president placed counter-insurgent efforts front and center of his administration, calling on legislators to make it a federal crime to conspire to ‘overthrow or destroy by force the government of the United States.’ The resultant Ku Klux Klan Act provided Grant authority to use the army to crush further white terror, even allowing him the right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in areas deemed insurrectionist. The bill’s passage was hardly assured—the opposition, as Smith wrote, encompassed everyone from ‘unabashed white supremacists, to civil libertarians, to Grant-haters of every variety’—but a visit from Grant to Capitol Hill rallied legislators to the cause. That April, nearly five years to the day after the Civil War officially ended at Appomattox, the anti-KKK bill passed. And Grant and his team didn’t hesitate to employ their new powers.”

Here’s what Grant did. “In northern Mississippi, a region saturated in white terror, U.S. attorneys secured nearly 1,000 indictments, convicting over half of those arrested. But it was in South Carolina in 1871 where the administration clamped down on outright insurrectionists — and hard. That year, Klan and white terror violence rampaged across the state, aimed directly at overthrowing elected officials. Declaring “a condition of lawlessness” in nine different counties, Grant used the new powers within the anti-KKK bill to their fullest extent. Suspending the writ of habeas corpus, rushing reinforcements to the state, the presence of the American infantry was enough to see thousands of Klansmen tuck tail and flee the state. With the KKK unwilling to face down the American military, members of the Army joined Akerman’s marshals to make hundreds of arrests. Federal grand juries filed thousands of indictments, with hundreds of convictions resulting. That combination of federal force and legal capacity appeared to work. The insurrectionists scattered, and the Klan stood whipped. ‘Grant’s willingness to bring the full legal and military authority of the government to bear had broken the Klan’s back and produced a dramatic decline in violence throughout the South,’ Smith wrote. The relatively peaceful 1872 election, in which Grant was re-elected in a landslide, attested to as much.”