And that’s a good thing.

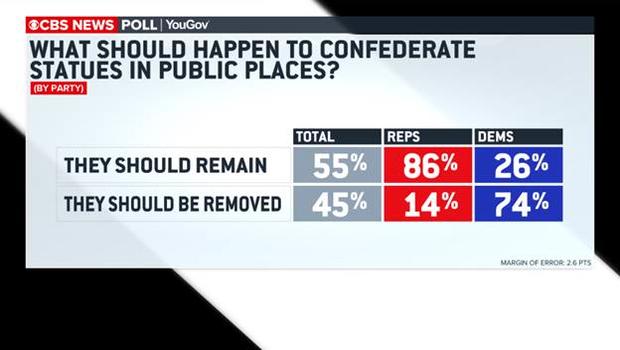

I came across this CBS News poll. “We asked Americans if Confederate statues should be removed from public places, and also if all statues of historical figures should be considered for removal, too, depending on what those figures did in their lives. We found divisions by party and race, and age. Three in four Democrats want Confederate statues removed, while more than 8 in 10 Republicans want them to remain.”

Here’s what the results show currently:

“Eight in 10 black Americans want Confederate statues and symbols removed, and while a slight majority of white Americans want them to remain, the opinion of white Americans is largely related to partisanship. Most white Democrats want the statues removed, while most white Republicans and independents want them to remain.

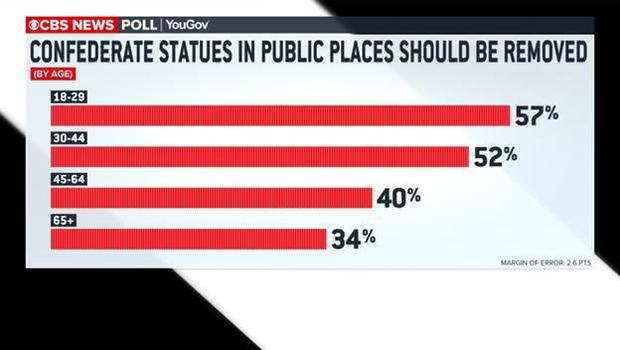

The future, though, looks like it could be much different. “Age matters: younger Americans are more likely to want Confederate statues removed — most do – while older Americans oppose; and younger Americans are much more likely to consider all historical statues for removal. Some of this, too, hews to partisanship.” As the dinosaurs die off, what will it look like in the future?

“By region, a slight majority of Americans in the South (56%) want the Confederate monuments to remain, but this is also true in the Midwest (57%) and West (55%). Only in the Northeast do a majority of Americans want Confederate monuments removed, and there just barely (51%). Here again, partisanship and race within regions factor more heavily than region itself.”

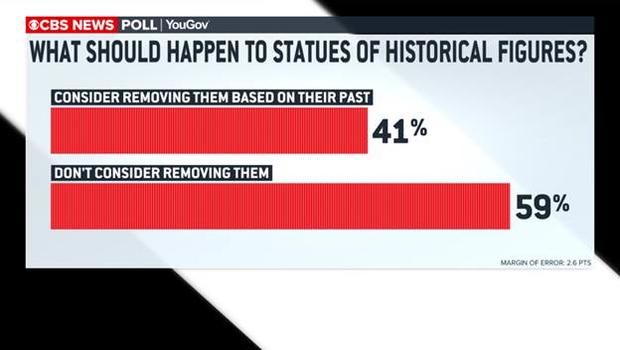

The poll also looked at other historical figures. “As protesters remove or try to remove a wider group of statues, it is Democrats who mostly would reconsider other figures, depending on what those figures did in their lives, while Americans overall are much less likely to back this idea. Forty-one percent of Americans think statues of all historical figures should be considered for potential removal. Democrats are most in favor, with two-thirds saying consider them all for removal, and large majorities of Republicans and independents saying not to consider a wider group for removal.”

“Views on this issue largely track with views on the recent protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Most who support the protests support both removal of Confederate monuments as well as considering whether all statues of historical figures should be removed based on what they did in life. Those who oppose the protests want the statues and monuments to remain in place.”

According to this article, “Long a symbol of pride to some and hatred to others, the Confederate battle flag is losing its place of official prominence 155 years after rebellious Southern states lost a war to perpetuate slavery. Mississippi’s Republican-controlled Legislature voted Sunday to remove the Civil War emblem from the state flag, a move that was both years in the making and notable for its swiftness amid a national debate over racial inequality following the police killing of George Floyd in Minnesota. Mississippi’s was the last state flag to include the design. NASCAR, born in the South and still popular in the region, banned the rebel banner from races earlier this month, and some Southern localities have removed memorials and statues dedicated to the Confederate cause. A similar round of Confederate flag and memorial removals was prompted five years ago by the slaying of nine Black people at a church in Charleston, South Carolina. A white supremacist was convicted of the shooting.”

In this June 24, 2020, file photo, construction workers remove the final soldier statue, which sat atop The Confederate War Memorial in downtown Dallas. (Ryan Michalesko/The Dallas Morning News via AP, File)

The article concludes, “During the past month, Gunn and Mississippi’s first-year lieutenant governor, Republican Delbert Hosemann, persuaded a diverse, bipartisan coalition of legislators that changing the flag was inevitable and they should be part of it. Hosemann is the great-grandson of a Confederate soldier, Lt. Rhett Miles, who was captured at Vicksburg and requested a pardon after the war ended in 1865. ‘After he had fought a war for four years, he admitted his transgressions and asked for full citizenship,’ Hosemann said during the debate. ‘If he were here today, he’d be proud of us.’ ”

Photo by Bill Green

In this story from Frederick, Maryland, we learn, “Three historic monuments at Mount Olivet Cemetery on South Market Street in Frederick were defaced overnight. Cemetery superintendent Ronald Pearcey said a life-sized statue placed in 1880 of an unknown Confederate solider was toppled from its base and shattered. He said it is likely not able to be repaired. Paint was also poured over the stone. Pearcey noted the area of the cemetery where more than 400 Confederate soldiers are buried was untouched as of about 8 p.m. Monday. The damage was discovered early Tuesday by bicyclists riding in the cemetery. Frederick Police responded and collected evidence and information. The two other monuments are also markers for the area where the soldiers are buried but those were damaged with bright red paint. Frederick’s Barbara Fritchie and Francis Scott Key are among the notable names buried at the cemetery.”

Next we have this story from Orangeburg, South Carolina. “Orangeburg City Council unanimously passed a resolution Tuesday to remove the 127-year-old Confederate statue located in Memorial Plaza. The resolution says, ‘The City of Orangeburg recognizes that the legacy of slavery, institutional segregation and ongoing systemic racism directly deepens racial division, and the City of Orangeburg is committed to the elimination of racial division and the promotion of racial equity and justice and desires to express this commitment through this resolution.’ The resolution notes that the statue will be immediately removed after approval and authorization by the South Carolina General Assembly. The Heritage Act of 2000 requires a two-thirds vote by the General Assembly to change or remove any local or state monument, marker, school or street erected or named in honor of the Confederacy or the Civil Rights Movement. State legislators previously told The T&D that the General Assembly will discuss repealing the Heritage Act, which would allow decisions on the changing or removal of structures to be made on the local level, in January 2021.”

In this story we learn the Prince William County School Board in Virginia renamed two schools previously named for Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. “Stonewall Jackson High School will be renamed Unity Reed High School to honor Arthur Reed, a long-time security assistant at the school, and Stonewall Middle School will be renamed Unity Braxton Middle, to honor Celestine and Carroll Braxton, a local educator and her veteran husband. According to an online petition in support of naming the high school after Reed, he was nicknamed the “Godfather of Stonewall” after he passed away. The high school is located just outside the city of Manassas. Celestine Braxton was an educator in the school division for 33 years who died in 2014. Braxton started teaching before racial segregation was ruled unconstitutional. Her husband, Carroll Braxton, is a decorated veteran. ‘This unity is possible because of remarkable and brave people like Celestine and Carroll Braxton,’ said School Board member Jennifer Wall, who represents the Gainesville District, where the middle school is located. A renaming committee of Wall, Chair Babur Lateef and school board members Adele Jackson of the Brentsville District and Lisa Zargarpur of Coles District recommended the new names. ‘In the end, it felt like the best way to encompass how the community felt,’ Jackson said about the new names. School board members said unity is a theme that is inspiring. ‘The Braxtons built and performed their lives with unity in mind clearly at all times, so I think this is great,’ Lateef said. School Board member Loree Williams said this is the time to rename schools. ‘[Both schools] have lived in a limbo of knowing we’ll get to this point, but not knowing when; I think this will bring some closure to that community,’ she said. School Board member Lillie Jessie, who represents the Occoquan District, asked during the meeting how much the renaming process will cost the division. ‘I think the public needs to know the cost and how we’re coming up with the money.’ Walts said the division will find the necessary funding to rename the schools. The school board also voted to name the middle school’s auditorium after John G. Miller, a principal at the school for 18 years who retired this year.”

Professor Peter Wood contributed this article about the John C. Calhoun statue. “More than a century after black emancipation, a monstrous statue of John C. Calhoun still hovered over the old port city. Even after the Freedom Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, a leading mastermind of white supremacy retained a central place of honor, high above Marion Square. As I came to understand how deeply his defense of racial oligarchy was still rooted in the soil of the Lowcountry, I wondered if he would remain there forever. Ever since Ozymandias named himself ‘King of Kings,’ monuments have come and gone. In Biblical times, Samson pulled down the Philistine temple to Dagon, and in Reformation England, Protestant zealots decapitated figures of Catholic saints. In Revolutionary Manhattan, patriots toppled a statue of George III, melting it into musket balls for their independence struggle. And the beat goes on in our own century. In 2003, U.S. troops in Baghdad used an armored vehicle to haul down a statue of the Iraqi despot Saddam Hussein from its marble plinth. In 2014, Ukrainians toppled so many Russian-made statues of Lenin (376 in February alone) that the era is remembered as ‘Leninfall.’ That same year, Michael Brown, a black youth in Ferguson, Missouri, died at the hands of a white police officer. His death followed the murder of Trayvon Martin, a seventeen-year-old African American, in Florida in 2012 and the acquittal of his killer the next year, sparking creation of the Black Lives Matter Movement. Anguished responses to these events brought into sharper focus many similar deaths that had been routinely ignored or explained away. The next year, 2015, a white supremacist massacred eight black parishioners and their pastor at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The young killer had taken selfies on local plantations and flaunted the Confederate flag. The murders he committed at Mother Emanuel, on June 17 took place scarcely two blocks from the lofty Calhoun monument. Ten days later, amid national grief and protests, a black student activist, Bree Newsome Bass, scaled a flagpole outside South Carolina’s State Capitol Building in Columbia and removed the Confederate battle flag. The beginnings of ‘Leefall’ in the United States could not be far behind. In February 2017, the Charlottesville City Council decided, by a 3-2 vote, to remove a towering monument in honor of General Robert E. Lee that had stood for a century. When Charlottesville’s equestrian statue was commissioned in 1917, Virginia-born Woodrow Wilson (whose name was also recently removed from Princeton’s public policy school) occupied the White House. The monument was dedicated in 1924, at the height of the Ku Klux Klan’s national resurgence. Word of its pending removal led white supremacists to rally in the university town in August 2017, resulting in the death of Heather Heyer and the injuring of 19 other people. Much had changed since Woodrow Wilson’s time in office; a century later, voters put an African American family in the White House for two terms. The Black Lives Matter Movement was gaining strength, so Leefall continued, in the face of predictable resistance. In May 2017, a likeness of Lee was one of four Confederate statues removed in New Orleans. Mayor Mitch Landrieu explained that these memorials belonged to the terrorism of the Lost Cause ‘as much as a burning cross on someone’s lawn; they were erected purposefully to send a strong message to all who walked in their shadows about who was still in charge in this city.’ Landrieu quoted Alexander H. Stephens, who proclaimed in 1861 that the cornerstone of the South’s new Confederacy was ‘the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.’ This long-ignored speech by the vice president of the Confederacy echoed Calhoun and prompted one modern historian to observe: ‘Stephens’s prophecy of the Confederacy’s future resembles nothing so much as Hitler’s prophecies of the Thousand-Year Reich. Nor are their theories very different. Stephens, unlike Hitler, spoke only of one particular race as inferior.’ Reading such pronouncements for the first time, a new and integrated generation of students began to sharpen their questioning about General Lee. Wasn’t he a wealthy slaveholder who had renounced his military oath of allegiance at West Point to fight against the United States as part of a pro-slavery secession movement? In August 2018, my own institution, Duke University, removed Lee’s statue from among the venerated historical figures placed at the entry to the university’s chapel in 1932. But could Charleston ever see a Calhoun-Fall? It took the city’s white elite almost 50 years to raise their statue honoring the U.S senator and vice president who had defined race-based enslavement as representing God’s natural order and a ‘positive good’ for all concerned. Born in upstate South Carolina in 1782, Calhoun died of tuberculosis in Washington, D.C., in 1850. Vessels in Charleston harbor lowered their flags when a ship returned his body to his home state, and the port city’s white minority went into mourning.”

Professor Wood then traces how the Calhoun statue came to be. “Church bells tolled, black crepe shrouded shop windows, and crowds lined the streets, wearing black armbands, as the senator was taken to his burial spot in St. Philip’s Churchyard. (The city’s black majority of 23,000 people shed few tears for the theoretician who had fostered the interests of his supposed master race and master class.) Four years after his death, local admirers organized the Ladies’ Calhoun Monument Association. The Charleston Mercury applauded their grandiose scheme for a soaring memorial as ‘chaste, yet elaborate.’ ‘The design,’ explains South Carolina historian Paul Starobin, ‘called for an edifice of about ninety-five feet in height. From the marble base, a flight of stairs would lead first to a set of four statues representing Liberty, Justice, Eloquence, and the Constitution, and then to a platform with a colonnade of Corinthian columns.’ At the pinnacle would stand ‘an immense, twelve-foot-high statue of Calhoun with his right arm extended upward and his hand pointed toward heaven.’ Hopes high, the Monument Association laid the cornerstone on Carolina Day, June 28, 1858. The ladies made sure it contained a lock of the great orator’s hair and a copy of his last Senate speech—a tirade against any sectional compromise that might limit slavery’s continental expansion. But the Civil War halted work on the memorial, and during Reconstruction Charleston’s Marion Square (known as Citadel Square until 1882) became a contested space. From 1865 until 1879, U.S. Army troops occupied the huge brick Citadel adjacent to the Square. (In 1822, in the aftermath of the Denmark Vesey slave revolt, the state legislature had authorized its construction to serve as an arsenal and guard house protecting white residents.) During Reconstruction, the new South Carolina National Guard, made up primarily of black South Carolinians, used the open field for drills and parades. Curious white onlookers watched the new game of baseball there, and African Americans gathered in the park for political rallies and civic celebrations. With the end of Reconstruction, Lost Cause elites reasserted local dominance. After renaming and landscaping the central green, they commissioned a Philadelphia sculptor to create a statue to adorn a new Calhoun memorial there. Plans again called for the pedestal to be graced with four allegorical figures—this time females representing History, Justice, Truth, and the Constitution. Only one of these figures arrived in time for the dedication of the long-delayed monument in April 1887 before a crowd of 20,000. When unveiled, there stood a larger-than-life representation of the orator, wagging his right index finger at all who passed. But this bronze reincarnation, atop a granite pedestal, lasted less than a decade. Standard accounts attribute the statue’s brief life to shortcomings in the sculptor’s awkward work, but black South Carolinians remember its demise differently. After all, when Boundary Street in front of Marion Square had been renamed Calhoun Street, they kept calling it Boundary, or they purposefully referred to it as Killhoun Street.”

This 1892 image by A. Wittemann appeared in Charleston, S.C. Illustrated. Four years later, the city’s Lost Cause elite replaced this memorial with a more presumptuous and far less accessible monument to Calhoun that stood until June 24, 2020. Image from Wikimedia Commons

Of course, African Americans weren’t consulted about the statue, but they had reactions, in which their white neighbors had no interest. “Mamie Garvin Fields, born in Charleston in 1888, recalled that as a small black girl she often passed by the new Calhoun monument with her friends. ‘Our white city fathers wanted to keep what he stood for alive,’ she recalled. So ‘they put up a life-size figure of John C. Calhoun preaching and stood it up on the Citadel Green, where it looked at you like another person in the park.’ A photograph made in 1892 shows a group of neatly dressed black girls, posing respectfully near the granite base. But as Fields made clear, such school children sensed the statue’s true purpose. ‘Blacks took the statue personally,’ Fields claimed in her powerful memoir, Lemon Swamp, explaining ways in which Calhoun, though long dead, had haunted her childhood. ‘As you passed by, here was Calhoun looking you in the face and telling you, ‘N—, you may not be a slave, but I am back to see you stay in your place.’ ‘ Mamie and her friends ‘didn’t like it. We used to carry something with us, if we knew we would be passing that way, in order to deface that statue—scratch up the coat, break the watch chain, try to knock off the nose—because he looked like he was telling you there was a place for ‘n—s’ and ‘n—s’ must stay there.’ According to Fields: ‘Children and adults beat up John C. Calhoun so badly that the whites had to come back and put him way up high, so we couldn’t get to him. That’s where he stands today,’ she concluded, ‘on a tall pedestal. He is so far away now until you can hardly tell what he looks like.’ ”

Professor Wood continues, “This apotheosis of Calhoun, elevating a new and even larger statue toward the heavens, was accomplished in 1896. The previous year, white citizens had adopted a new constitution that disenfranchised black Carolinians, and they had sent their notoriously racist governor, ‘Pitchfork Ben’ Tillman, to represent South Carolina in the U.S. Senate. ‘We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will,’ Tillman proclaimed. ‘We have never believed him to be the equal of the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.’ Spurred on by such racist demagoguery, well publicized mob violence continued across the state. In 1896, the documented lynchings of black men in South Carolina included Calvin Kennedy (Aiken, February 29), Abe Thomson (Spartanburg, March 1), Thomas Price (Kershaw, April 19); and Dan Dicks (Aiken, July 17). Revising Calhoun’s monument that year moved him above the reach of his detractors while still assuring that his glowering visage would dominate the urban landscape. He remained there when Mamie Fields died in 1987, at age 99. Calhoun’s likeness still presided over central Charleston two years ago, when I joined a group of Colorado school teachers and students traveling to South Carolina to explore the roots of American racism. With statues of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis coming down across the region, we speculated when, if ever, this incongruous relic might disappear. Several of the idealistic high school students from the West were dismayed to learn that local officials had only floated tepid proposals for placing an ‘explanatory’ plaque at the column’s base, or erecting a smaller monument nearby for someone who opposed enslavement. But after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the wind shifted dramatically. Suddenly the monument seemed even more offensive, an ever-present poke in the eye to local black residents and to distant visitors. When word spread that the Charleston City Council had voted unanimously to remove the domineering figure from his skyscraping column, I thought of a comment Walt Whitman recorded at the end of the Civil War. After Confederate forces had surrendered at Appomattox Court House, the poet overheard a Union soldier observe that the true monuments to Calhoun were the wasted farms and gaunt chimneys scattered over the South. Most of those gaunt chimneys fell long ago, and once-wasted farms now grow soybeans or shoulder suburban sprawl. But the unreachable figure of Calhoun still dominated the Charleston skyline, even after the National Park Service, in 2016, turned back a formal request from an eminent civic group. The Charleston World Heritage Coalition had asked the NPS to nominate the city to the United Nations as a worthy site to be included on UNESCO’s official and prestigious World Heritage List. The rejection sent a clear message to Charleston’s civic leaders about their aspirations to gain UN recognition for Charleston as a world heritage cultural center and to increase tourism with a new International African American Museum. How could these efforts succeed if the city continued to leave in place such a contradictory and outdated tribute to pro-slavery doctrine? So on June 24, 162 years after devoted ladies placed a lock of their hero’s hair in the first cornerstone, a 17-hour effort by city workers with cranes and welding torches brought the burdensome figure back to earth. The moment for Calhoun-Fall had finally arrived.”

The Lowndes County Commission voted Monday to remove a Confederate monument that stands in the Hayneville town square.

This article from Lowndes County, Alabama, tells us, “The Lowndes County Commission voted Monday to remove a Confederate monument that stands in the Hayneville town square. According to the commission, the statue, constructed sometime in 1940, stands before the Lowndes County Courthouse. It will be moved, but the timing for the removal is unclear. Commission Chairman Carnell McAlpine said if necessary they will pay the $25,000 fine set by state law to preserve monuments. He said due to recent events of racial injustice, the commission felt it was time for a change. ‘We looked at the things that’s been going on in the United States for the last month or so, as far as justice and the George Floyd incident and some other cases, and we just feel like at this point, with Lowndes County being in the Black Belt, a very race-diversed county, we just felt like it was time for us to make a change and remove it and move forward,’ McAlpine said. Jacqueline Thomas, county administrator, confirmed the removal vote was unanimous.”

In this article we learn something of what Frederick Douglass thought of monuments. “Frederick Douglass, with typical historical foresight, outlined a solution to the current impasse over a statue he dedicated in Washington, D.C., in 1876. Erected a few blocks from the U.S. Capitol, in a square called Lincoln Park, the so-called Emancipation Memorial depicts Abraham Lincoln standing beside a formerly enslaved African-American man in broken shackles, down on one knee—rising or crouching, depending on who you ask. As the nation continues to debate the meaning of monuments and memorials, and as local governments and protesters alike take them down, the Lincoln Park sculpture presents a dispute with multiple shades of gray. Earlier this month, protestors with the group Freedom Neighborhood rallied at the park, managed by the National Park Service, to discuss pulling down the statue, with many in the crowd calling for its removal. They had the support of Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District’s sole representative in Congress, who announced her intention to introduce legislation to have the Lincoln statue removed and ‘placed in a museum.’ Since then, a variety of voices have risen up, some in favor of leaving the monument in place, others seeking to tear it down (before writing this essay, the two of us were split), and still others joining Holmes Norton’s initiative to have it legally removed. In an essay for the Washington Post, Yale historian and Douglass biographer David W. Blight called for an arts commission to be established to preserve the original monument while adding new statues to the site. It turns out Frederick Douglass had this idea first.

The newly discovered letter written by Frederick Douglass in 1876. (Courtesy of the authors)

“ ‘There is room in Lincoln park [sic] for another monument,’ he urged in a letter published in the National Republican newspaper just days after the ceremony, ‘and I throw out this suggestion to the end that it may be taken up and acted upon.’ As far as we can ascertain, Douglass’s letter has never been republished since it was written. Fortunately, in coming to light again at this particular moment, his forgotten letter and the details of his suggestion teach valuable lessons about how great historical change occurs, how limited all monuments are in conveying historical truth, and how opportunities can always be found for dialogue in public spaces. In the park, a plaque on the pedestal identifies the Thomas Ball sculpture as ‘Freedom’s Memorial’ (Ball called his artwork ‘Emancipation Group’). The plaque explains that the sculpture was built ‘with funds contributed solely by emancipated citizens of the United States,’ beginning with ‘the first contribution of five dollars … made by Charlotte Scott a freed woman of Virginia, being her first earnings in freedom.’ She had the original idea, ‘on the day she heard of President Lincoln’s death to build a monument to his memory.’ With this act, Scott had secured immortality; her 1891 obituary in the Washington Evening Star, eulogized that her ‘name, at one time, was doubtless upon the lips of every man and woman in the United States and is now read by the thousands who annually visit the Lincoln statue at Lincoln Park.’ Indeed, the Washington Bee, an important black newspaper of the era, proudly referred its readers to ‘the Charlotte Scott Emancipation statue in Lincoln Park.’ Scott’s brainchild and philanthropic achievement today stands surrounded: first by protective fencing, then by armed guards wearing Kevlar vests, then by protesters, counter-protesters, onlookers, neighbors and journalists, and finally by a nation in which many are seeing the legacies of slavery for the first time. Not since 1876, at least, has the imagery of kneeling—as torture and as protest—been so painfully and widely seen.”

The article continues, “Ironically, Ball had changed his original design in an attempt to convey what we now recognize as the ‘agency’ of enslaved people. Having first modeled an idealized, kneeling figure from his own white body, Ball was persuaded to rework the pose based on a photograph of an actual freedman named Archer Alexander. The new model had already made history as the last enslaved Missourian to be captured under the infamous Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (the arrest took place in 1863, in the middle of the Civil War). A white speaker at the dedication recounted the statue’s redesign. No longer anonymous and ‘passive, receiving the boon of freedom from the hand of the liberator,’ the new rendering with Archer Alexander depicted ‘an AGENT IN HIS OWN DELIVERANCE … exerting his own strength with strained muscles in breaking the chain which had bound him.’ Thus the statue imparted a ‘greater degree of dignity and vigor, as well as of historical accuracy.’ Few today see it that way—and neither did Frederick Douglass in 1876. Even as he delivered the dedication address, Frederick Douglass was uncomfortable with the statue’s racial hierarchy and simplistic depiction of historical change. Having known and advised the President in several unprecedented White House meetings, Douglass stated bluntly to the assembled crowd of dignitaries and ordinaries that Lincoln ‘was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.’ Yet, Douglass acknowledged that Lincoln’s slow road to emancipation had been the fastest strategy for success. ‘Had he put the abolition of slavery before the salvation of the Union, he would have inevitably driven from him a powerful class of the American people and rendered resistance to rebellion impossible,’ Douglass orated. ‘Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.’ Douglass saw Lincoln not as a savior but as a collaborator, with more ardent activists including the enslaved themselves, in ending slavery. With so much more to do, he hoped that the Emancipation statue would empower African Americans to define Lincoln’s legacy for themselves. ‘In doing honor to the memory of our friend and liberator,”’ he said at the conclusion of his dedication speech, ‘we have been doing highest honors to ourselves and those who come after us.’ That’s us: an unsettled nation occupying concentric circles around a memorial that Douglass saw as unfinished. The incompleteness is what prompted the critique and ‘suggestion’ he made in the letter we found written to the Washington National Republican, a Republican publication that Douglass, who lived in D.C., would have read. ‘Admirable as is the monument by Mr. Ball in Lincoln park,’ he began, ‘it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth, and perhaps no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject which it might be designed to illustrate.’ Douglass had spoken beneath the cast bronze base that reads “EMANCIPATION,” not “emancipator.” He understood that process as both collaborative and incomplete. ‘The mere act of breaking the negro’s chains was the act of Abraham Lincoln, and is beautifully expressed in this monument,’ his letter explained. But the 15th Amendment and black male suffrage had come under President Ulysses S. Grant, ‘and this is nowhere seen in the Lincoln monument.’ (Douglass’ letter may be implying that Grant, too, deserved a monument in Lincoln Park; some newspaper editors read it that way in 1876.) Douglass’s main point was that the statue did not make visible ‘the whole truth’ that enslaved men and women had resisted, run away, protested and enlisted in the cause of their own freedom. Despite its redesign, the unveiled ’emancipation group’ fell far short of this most important whole truth. ‘The negro here, though rising,’ Douglass concluded, ‘is still on his knees and nude.’ The longtime activist’s palpable weariness anticipated and predicted ours. ‘What I want to see before I die,’ he sighed, ‘is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.’ And so his suggestion: Lincoln Park, two blocks wide and one block long, has room for another statue.”

The article concludes, “Douglass’s solution was not to remove the memorial he dedicated yet promptly criticized, nor to replace it with another one that would also fail, as any single design will do, to ‘tell the whole truth of any subject.’ No one memorial could do justice, literally, to an ugly truth so complex as the history of American slavery and the ongoing, ‘unfinished work‘ (as Lincoln said at Gettysburg) of freedom. Nobody would have needed to explain this to the formerly enslaved benefactors like Charlotte Scott, but they made their public gift just the same. And yet if the statue is to stand there any longer, it should no longer stand alone. Who would be more deserving of honor with an additional statue than the freedwoman who conceived of the monument? In fact, Charlotte Scott attended its dedication as a guest of honor and was photographed about that time. A new plaque could tell Archer Alexander’s story. Add to these a new bronze of Frederick Douglass, the thundering orator, standing ‘erect on his feet like a man’ beside the statue he dedicated in 1876. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should juxtapose Douglass and Lincoln, as actual historical collaborators, thus creating a new ‘Emancipation Group’ of Scott, Douglass, Lincoln, Archer Alexander—and Bethune. This would create an entirely new memorial that incorporates and preserves, yet redefines, the old one, just as the present is always redefining the past. In a final touch, add to the old pedestal the text of Douglass’s powerful yet succinct letter, which will charge every future visitor to understand ‘the whole truth’ of the single word above, cast in bronze – EMANCIPATION – as a collaborative process that must forever ‘be taken up and acted upon.’ ”

This article tells us the Boston Arts Commission decided to move Boston’s replica of the Freedmen’s Monument. It tells us, “Members of the Boston Art Commission voted unanimously to remove Boston’s copy of Thomas Ball’s ‘Emancipation Memorial’ sculpture, which portrays an enslaved man at the feet of Abraham Lincoln. After nearly two hours of public comment Tuesday night, with people arguing both for and against keeping the statue, the board charged its staff to look at next steps for the sculpture, including where to store it temporarily and what could replace it. The bronze sculpture currently sits on city property in Park Square. It would cost at least $15,000 to remove, according to Karin Goodfellow, the city’s director of public art. All board members agreed on giving more context, education, and transparency to the sculpture’s history and future. The board said it did not plan to remove the piece of art completely from the city’s collection. Removal could mean loaning it to a museum or putting it into storage. The commission said it would plan to hold a public event to ‘acknowledge the statue’s history and inform the public.’ During public comment, many local residents said the sculpture made them uncomfortable, while others said they felt it reinforced a racist and paternalistic view of Black people. In her closing remarks, commission member and artist Ekua Holmes said, ‘What I heard today is that it hurts to look at this piece. And I feel like on the Boston landscape we should not have works that bring shame to any group of people that are citizens, not just of Boston, but of the United States.’ ”

We also have this blog post from Professor Karen Cox, who is perhaps the leading scholar on confederate monuments. She writes, “Today voter suppression in several states, made worse by gerrymandered districts like in my home state of North Carolina, makes it difficult to near impossible to elect officials who will change laws, including those intended to preserve Confederate monuments. In fact, the history of Confederate monuments is tied directly to the disenfranchisement of black voters and has been since the 1890s. When the monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in Richmond in 1890, African Americans in that city recognized it as a symbol of their own oppression and its links to suppressing their right to vote. Barely a week after unveiling of the Lee Monument, John Mitchell, Jr. the editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, penned an editorial in which he warned readers that the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back, especially the right to vote. ‘No species of political crimes has been worse than that which wiped the names of thousands of bona-fide Colored Republican voters from the Registration books of this state,’ Mitchell wrote. He claimed, rightly, that refusing to allow black men to vote was a ‘direct violation of the law,’ and blamed state officials sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution for illegally scrubbing the names of men from voter rolls, marking them ‘dead’ or having moved to another state, when neither was true.”

Professor Cox also writes, “In the decade following the Lee Monument’s unveiling, one southern state after another passed laws disenfranchising black men, a right that was guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment. The elimination of black voters, not only by law but through violent white supremacy, and the creation of Jim Crow legislation that limited black freedom, all occurred during the very same years that the hundreds of Confederate monuments now at issue were built across the South. And black southerners did not have a say in the matter, because their rights as citizens had been obliterated. Even in towns where they represented the majority of the population, they could not vote to prevent them from being built in the center of towns where they lived, they could not petition to have them removed, and they could not protest them publicly out of fear of reprisal, although they found ways of doing so out of the view of southern whites. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and especially the Voting Rights Act of 1965, black southerners not only voted, but elected people to office who looked like them. Local city councils increasingly had black representation and over the course of the next few decades African Americans throughout the region challenged the existence of Confederate symbols on the grounds of local and state government, which were supposed to be democratic public spaces that represented all citizens. But in the 1990s, as in the 1890s, Republicans found another way to constrict black political power via majority/minority districts. This form of gerrymandering, sometimes called affirmative gerrymandering, did not violate Voting Rights Act regulations. Rather, it consolidated the minority vote, limiting a black majority to one district. As political scientist Angie Maxwell explains, while these new lines ensured minority representation, ‘it bleached the other districts white, allowing the GOP to pick up seats fast in the South.’ The result in 1994 was the Republican takeover of the House. This model of Republican-favored gerrymandering grew worse in the South in the early twentieth century, and its implementation not only guaranteed more GOP seats in Congress, it led to a similar plan that ensured GOP majorities at the state level. And these are the very state legislatures that passed monument laws designed to preserve Confederate monuments in publicly owned spaces. The gutting of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 in the context of Confederate monument removal is critical to our understanding of this moment of protests. By suppressing the rights of black voters, as well as white voters who support this movement, GOP-led state legislatures have not only prevented these voters from exercising their rights as citizens, they have usurped local control to remove monuments legally. In essence, they have left no other options for redressing this issue than to take to the streets to demonstrate their frustration.”

Professor Cox concludes, “Monuments are ultimately local objects and what becomes of them will be determined by the local communities in which they reside. And while it appears that the tide has turned, as several southern cities and towns have voted or are voting to remove monuments, the state laws remain a barrier to removal. There also exists a very real concern that once GOP-led southern legislatures return to session, Republicans will close any existing loopholes in monument legislation, which will represent yet another backlash to progress. And once again, there will be no legal redress. And given voter suppression, it removes the possibility of electing officials to amend laws that allow local communities to decide the fate of Confederate monuments. Under those circumstances, the cycle of protest will begin again.”

Stone Mountain, in Georgia, was turned into an enormous confederate monument. This article has some suggestions on what can be done with it. “It is too big to just tear down, like they are doing with statues in Richmond and elsewhere, but something is going to happen with it eventually. Anti-racist sentiment is growing, and the makeup of Georgia’s population is changing so fast that some kind of modification is inevitable. And while I believe decisions about what ultimately happens there should emerge from meaningful public engagement, I don’t believe we have to wait any longer to make change. Below are some ideas we can start to implement now.”

First, the article gives some historical context: “Stone Mountain is a massive geological aberration. Often incorrectly identified as granite, the exposed rock is technically a ‘quartz monzonite dome monadnock’ that extends underground for miles in every direction. The visible portion rises 1,686ft (514 meters) above sea level, or 825ft above the surrounding Georgia piedmont. Located 14 miles east of downtown Atlanta, it sits within a 3,200-acre (1,294-hectare) forest-cum-theme-park that is owned by the state of Georgia and managed by the Stone Mountain Memorial Association. It is cited as ‘Georgia’s most visited attraction, drawing nearly 4 million guests each year’. Best known for its laser-light show that runs every night throughout the summer, the park also offers hiking, fishing, camping, paddle boats, an excursion train, a golf course, a Marriott conference center, educational exhibits and a handful of memorials to white supremacy. The icon of Stone Mountain Park is one of those memorials. It’s also the largest bas-relief sculpture in the world. Occupying the steep northern slope of the mountain and measuring 76ft tall by 158ft wide, the carving depicts the president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, along with the Confederate generals Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson. They are riding their favorite horses with their hats over their hearts. Like most southern civil war memorials, their real purpose is to instill in us a 20th-century romanticized narrative about the American south that helps maintain white supremacy through a segregated and unequal society.

A cable car passes the carvings of Confederate civil war leaders as it returns visitors from the top of Stone Mountain in Georgia. Photograph: John Bazemore/AP

“The sculpture is an irreparable scar on an ancient mountain with a long history of habitation and use by indigenous people. More blatantly offensive, however, is the sculpture’s undeniable reverence for hate and violence and the honor it bestows on the generals, who, by definition, were American traitors. We need to change that, but before we jump to ideas about the fate of the sculpture itself, it is important to dismiss any claim of valor or heritage so that we can all agree that that fate – whatever it is – is long overdue. The story of the sculpture’s ‘heritage’ began one November night in 1915, 50 years after the end of the American civil war. Fifteen men burned a cross atop the mountain and marked the founding of the modern Ku Klux Klan. The next year, Samuel Venable, a Klansman and quarry operator who owned the property, deeded its north face to the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), which planned the original carving. They commissioned the work to a Klan sympathizer – a sculptor named Gutzon Borglum, who after quitting the project in 1925, would go on to carve Mount Rushmore. Another sculptor continued the project for three years until the UDC ran out of money. At that point, only Robert E Lee’s head was complete, and the project languished for 30 years. In 1958, just four years after Brown v Board of Education and two years after the Confederate battle emblem was added to Georgia’s flag (it was removed in 2001), the state purchased Stone Mountain for the creation of a Confederate memorial park. Five years later, in 1963 – the very same year that Martin Luther King proclaimed in his I Have A Dream speech, ‘Let freedom ring from the Stone Mountain of Georgia!’ – the state restarted the effort to finish the Confederate sculpture. Historian Grace Hale explains that to white state leaders at that time, ‘the carving would demonstrate to the rest of the nation that ‘progress’ meant not Black rights but the maintenance of white supremacy’. Work on the sculpture continued throughout the 1960s while nearby Atlanta emerged as the cradle of the American civil rights movement, as the federal government passed landmark legislation such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and even after King was assassinated in 1968. Remarkably, only two years later in 1970, Spiro Agnew, the vice-president of the United States, was a participant at the sculpture’s unveiling. And over time, the park continued to evolve, with additional homages to white supremacy, including the names of streets like Robert E Lee Boulevard and Stonewall Jackson Drive, and a prominent role for the still-flying Confederate battle flag. Meanwhile, the suburbs of Atlanta grew up around the park. And in an interesting twist of fate, by the end of the century, Atlanta’s suburbanizing African American middle class found themselves living in these once-white neighborhoods. Even more surprisingly, perhaps, despite the park’s overtly racist iconography, park visitors today are decidedly diverse, and modest efforts have been made to contextualize the Confederate memorials. For example, the end of the laser-light show animates the Confederate generals, who break their swords and gallop into the books of American history.”

We next move on to what can be done: “Today, with that perspective as our starting place, we must begin to transform Stone Mountain Park into a more aspirational symbol for our future. That will take time, but to set the tone for that dialogue, here are four things we can do now:

1. Stop cleaning the sculpture

State law protects the sculpture from destruction but does not require it to be clean. It remains clear of vegetation only through effort and expense. Trees and plants grow easily from the mountain’s other cracks and crevices. We should allow growth to also overtake the sculpture’s many clefts and crinkles as they naturally collect organic material and allow moss and lichen to obscure its details. We should blast it with soil to encourage such growth and consider this new camouflage as a deliberate creative act, transforming the sculpture into a memorial to the end of the war – not to the traitors who led it.

2. Stop mowing the lawn

Allow the Memorial Lawn to grow into a forest. It is not protected by the law. A major problem with Stone Mountain is the formal, triumphant view of the sculpture, making the entire park a celebration of white supremacy. Elimination of this view will also mean the end of the laser-light show – consider a replacement event that similarly draws people together, but instead around new symbols of peace and justice.

3. Update the park’s identity

Eliminate any other remaining references to the Confederacy. These are not protected by the law. Conduct a quick re-evaluation of all the names, signage, narrative, flags and iconography throughout the park and remove all problematic references, including the names of streets and lakes, programming and online content. Acknowledging the somber weight of history here, this should also include removal of the theme-park activities below the sculpture.

4. Plan a new park

Begin a dialogue for more sweeping changes at the park that will inspire required changes to state law. Consider an international design competition that refocuses the 3,200-acre park around its namesake geological feature and transforms it into a new symbol of peace and reconciliation. Consider proposals for future permanent modifications to the sculpture itself, as well as existing proposals for a mountaintop carillon that honors King’s dream by literally letting freedom ring at the top of every hour. Include the transformation of Memorial Hall into a Memorial to the End of the Confederacy – an honest interpretation of life in the American south, the civil war, the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, and subsequent efforts to romanticize the “Lost Cause” through memorials like Stone Mountain’s 1970 carving.”

The article concludes, “These proposed changes will not be enough. They are only a start, and only small part of a larger effort to ensure that the design and use of public land and public spaces reflect our highest values, and that those values actually shape the laws that regulate our land. And while we don’t know if challenging the law that protects Stone Mountain will work immediately, we do know that eventually, change is going to come. We have this fleeting opportunity to try to make it happen now, and to tell our children we stood up to hate. If we wait, our children will have to do the work for us.”

This article considers what it would take to remove the sculptures from the monument. ” ‘You could pack it full of dynamite and blow it all the way to Lawrenceville, but you don’t want to create such a hazard,’ said Ben Bentkowski, president of the Atlanta Geological Society. ‘Removing a gigantic sculpture off the side of a mountain is not a trivial undertaking.’ We asked Bentkowski and other geologists to leave aside political considerations and just think about the logistics of erasing the giant sculpture. They all agreed that removing it is an achievable, if costly, engineering feat. Here’s how it might go. And it does not involve a giant sandblaster. First, there would be the quiet, tedious work: months, if not years of environmental impact and engineering feasibility studies, Bentkowski said. The economic impact on the surrounding theme park and attractions would have to be considered as well, since those would probably have to close during the demolition. Contractors would have to bid for the work, exposing themselves to dangerous backlash. Companies that bid to remove Confederate statuary in New Orleans this year received death threats causing some to back out of consideration. The crews who did the work wore flak vests, helmets and masks. Once a team was put in place, how would they move forward?”

According to the article, “There’s the non-explosive option, said Derric Iles, the state geologist for South Dakota, home to Mt. Rushmore, which was carved by the first of three sculptors who worked on Stone Mountain. Air chisels and air hammers could be used, but only if ‘you have all the time in the world,’ Iles said. And money. So that brings it back to explosives. If you’ve ever descended into the bowels of the Peachtree Center MARTA Station, you’ve seen what targeted explosives can create; tunnels big enough for a train to run through. The stone walls bear the scarring from explosives and the holes bored to put them in place. That’s what would happen at Stone Mountain. Work stations would be built on top of the mountain, and scaffolding to support the workers, would be operating hundreds of feet up. Project managers would have to decide whether they want to blow the whole sculpture or preserve parts of it for some other use. Stone Mountain rock has been used for foundations, from metro Atlanta bungalows to the Lincoln Memorial to parts of the Panama Canal. The workers would drill holes into the rock that would hold the explosive charges. It wouldn’t happen quickly. Drilling is complicated, and doing it safely could take six months to a year, Bentkowski said. At least one worker fell to his death during the multi-decade span it took to create the relief there today. With the holes in place, bit by bit, the image would be blasted away, but the fallen debris would create an excavation site. The rubble would have to carted away at every stage, adding time and expense. It wouldn’t be the only time explosives have been used on the mountain. The original version of the memorial begun by Gutzon Borglum, in the 1920s, only got as far as the sculpting of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s head. Borglum didn’t complete the project and went out west to blast away rock that became Mt. Rushmore. But the work he left behind on Stone Mountain was removed with dynamite by the second sculptor, Augustus Lukeman. Lukeman then chiseled a new vision, one that became the three horsemen: Lee, Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson. The whole deconstruction process could take a year or more, and a gaping, three-acre hole would be left. What would go in its place? ‘Whatever you could find the funding and social will for,’ said Bentkowksi.”

The article continues, “Explosives aren’t the only option. The relief could be covered, said Robert Hatcher, distinguished scientist in geology at the University of Tennessee. The figures would be smoothed down, then the area filled with concrete. ‘It wouldn’t be very pretty,’ Hatcher said. ‘It would deface the mountain. I guess you could paint a mural over it.’ It might not be as disruptive and expensive as mining away the sculpture, he said, but it would still take millions of dollars in taxpayer money to complete.”

The article concludes, “Whatever happens to the contentious memorial, one thing is certain, Bentkowski said. ‘It’s a really big piece of rock that’s been there hundreds of millions of years, and once we humans get done messing with it, it’ll be there hundreds of millions of more years,’ he said.”

This article tells us the Alabama Department of Archives & History admits for years it had been lying about history and apologizes for those lies. “The Alabama Department of Archives & History said in a statement today that for much of the 20th century it promoted a view of history that favored the Confederacy and failed to document the lives and contributions of Black Alabamians. Archives & History Director Steve Murray said he drafted the “Statement of Recommitment” that was approved by the agency’s Board of Trustees. Read the statement. ‘The State of Alabama founded the department in 1901 to address a lack of proper management of government records, but also to serve a white southern concern for the preservation of Confederate history and the promotion of Lost Cause ideals,’ the statement says. ‘For well over a half-century, the agency committed extensive resources to the acquisition of Confederate records and artifacts while declining to acquire and preserve materials documenting the lives and contributions of African Americans in Alabama.’ While acknowledging its former role in presenting a distorted view of Alabama’s past, the agency pledged to continue efforts of the previous four decades to tell inclusive accounts of history.”

According to the article, ” ‘Like every other organization in the country and individuals we have been reflecting on the turmoil that we’ve seen in the last month and the calls for social justice and racial justice and how that discussion has spilled over into debate about public commemoration and kind of the historical landscape,’ Murray said. ‘Our agency has done a lot of reflection during that time and thought it appropriate and timely for us to make a statement about our perspective in terms of how our work relates to the issues that our country is dealing with right now, and how our agency had a distinctive role in the early 20th century in shaping some of the history that’s being talked about now.’ The statement says systemic racism remains a reality in America even though most people believe in racial equality. ‘The decline of overt bigotry in mainstream society has not erased the legacies of blatantly racist systems that operated for hundreds of years,’ the statement says. Derryn Moten, a professor of history and political science at Alabama State University, called the statement bold. ‘I think it’s one of the best statements that I have read coming out of any institution since George Floyd’s death,’ Moten said. ‘I think it’s forthright. I think it’s considerate. I commend Director Steve Murray, whom I know, and the board for this statement. Particularly the frankness and the candor for which this statement speaks about the history and the legacy of the Confederacy.’ Archives & History said it is committed to developing programs and exhibits to promote a deeper understanding of the roots and consequences of racism. An example was last year’s exhibit, ‘We the People: Alabama’s Defining Documents,’ which displayed and explained the origins of the six constitutions governing Alabama since statehood began in 1819. The current constitution, ratified in 1901 and heavily amended, was intended to preserve white supremacy and suppress the black vote. ‘This isn’t about tearing down our state or the people who built Alabama,’ Murray said. ‘It’s about understanding them as flawed human beings who just like us fall short of our aspirations quite frequently. But the reality is, some bad decisions were made along the way. And we collectively are continuing to pay a price for that. This is not a situation where only African Americans in the past paid a price for that. It continues to affect our people today. It continues to affect all of us because it rolls into issues related to access to education, to pockets of economic prosperity as opposed to persistent areas of widespread poverty.’ ”

We have this video from NBC News. Its description reads, “From Charlottesville to Selma, NBC’s Trymaine Lee and the New York Times’ John Eligon travel the South to understand hate, heritage, and the legacy of the Confederacy.” Of course they meet a couple of SCV types spouting the typical neoconfederate lies.

This video is a discussion with Kevin Levin regarding, among other things, the black confederate lie and confederate monuments.

Some may be wondering about confederate monuments in national parks such as Gettysburg. We have this article, which tells us, “The National Park Service released a statement Friday saying the agency will not alter, relocate, obscure or remove any monuments at Gettysburg National Military Park, even ‘when they are deemed inaccurate or incompatible with prevailing present-day values.’ The statement, released onto the park’s website, describes the Confederate monuments at Gettysburg as representing an ‘important, if controversial, chapter in our nation’s history.’ It also explains that some monuments within the park cannot be removed because they were specifically authorized by Congress or might predate the park itself, making them a protected park resource. In either situation, legislation could be necessary for the NPS to remove a monument, as the agency must comply with laws such as the National Historic Preservation Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, the statement said. Additionally, some monuments have existed in the park long enough to be considered historic features. ‘A key aspect of their historical interest is that they reflect the knowledge, attitudes, and tastes of the people who designed and placed them,’ the statement said. The NPS maintains and interprets monuments, markers, and plaques that commemorate and memorialize those who fought during the Civil War. It is committed to preserving these memorials while simultaneously educating visitors holistically about the actions, motivations, and causes of the soldiers and states they commemorate, the statement said. The Director of the NPS may make an exception to the NPS policy of non-removal.”

We also have this report from CNN with Professor Scott Hancock of Gettysburg College discussing the confederate monuments at Gettysburg.

I think a consensus has been reached about these monuments in public spaces. The post also displays vandalism in a cemetery. It is only a matter of time until such actions find their way to battlefields.

Is this just about public property? Are grave sites not sacrosanct ?

I know the argument about providing context at battlefields, which is really not necessary because the NPS provides plenty at their Visitor Centers.

Thanks for taking the time to comment. When governments make it impossible for there to be an open process to remove racist monuments, then they make it necessary for extralegal action to remove them. When that happens, things get out of control.

Visitors don’t need to go to the Visitors Centers in order to visit battlefields, so in many cases they don’t see whatever contextualization is provided at the VCs. That’s why context at the monument is needed.

Also remember – battlefields are considered gravesites. The monuments at Gettysburg and other fields are afforded the appropriate protections.

No, they aren’t. For national battlefields, Congress can determine to take down any monuments it wants. For states, it would be the state government. That’s a function of who owns the land. That’s the only protection they have.

Well, they are considered gravesites. Removing monuments would require legislative action. I’m sensing this is something you would welcome. There is no controversy here, despite the efforts of a loan academic with no real ties to the battlefield(beyond geography.)

If you say take down monuments in public squares etc.. Then there’s agreement. This push to remove battlefield monuments can only be seen argumentative.

No, they’re not considered grave sites. There are probably some undiscovered graves on certain battlefields, but that doesn’t make the battlefield a grave site. There has been plenty of surveying around monument sites, and we can be confident there are no graves around the monuments with the exception of the National Cemetery. To be perfectly frank, I don’t care about confederate monuments on battlefields. If they attract white supremacists like they did on July 4, then it might be better if they were gone, but in reality it doesn’t matter a bit to me. They can stay or go as far as I’m concerned. If they stay I’d like to see them contextualized. I’m not sure what you mean about an academic on loan somewhere.

I really haven’t seen much of a push to remove confederate monuments from battlefields–just a few isolated folks here and there.