With all the things that happened in the past 24 hours, I’m wondering if I can get it all in one post.

According to this story, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper wants to move three confederate monuments off the grounds of the state’s capitol building. “Gov. Roy Cooper has sent a formal request to move three Confederate monuments from the State Capitol grounds to a historic site in Johnston County. Machelle Sanders, secretary of the Department of Administration and a Cooper appointee, sent the petition to the state Historical Commission. A 2015 state law that took power away from elected officials to decide on their own to move or remove monuments requires commission approval for changes. But the law appears to limit what the commission can do. Cooper, a Democrat, wants the monuments moved to the Bentonville Battlefield, site of a Civil War battle. ‘Relocating these monuments to a historic Civil War site will help us preserve them and provide context for their history,’ Sanders said in a statement. … Cooper called for repeal of the 2015 law – a move Senate leader Phil Berger, a Republican, said he did not support. ‘The governor’s decision to spend this evening working to remove decades-old monuments instead of remaining laser-focused on the major hurricane bearing down on the southeast shows he is continuing to concentrate on the wrong priorities,’ Shelly Carver, a spokeswoman for Berger, said in a statement Friday. It’s unclear whether the commission has the authority to approve moving the monuments. Earlier, Cooper said the commission’s powers were narrow, which is why he wanted the law repealed. The petition, however, says the commission can make the call on the Capitol monuments. The monuments need to be moved so they can be preserved, the petition says. Under the law, monuments that are permanently relocated have to go to sites of similar ‘prominence, honor, visibility, (and) availability.’ They can’t go to a museum, cemetery, or mausoleum unless they originated from a similar place. The three monuments the Cooper administration wants moved are the 1985 Confederate monument, the Henry Lawson Wyatt monument, which depicts the first Confederate soldier to die in battle, and the North Carolina Women of the Confederacy monument. The Historical Commission’s next meeting is Sept. 22. Three of 11 voting members are Cooper appointees.”

According to this story on the same issue, “Cooper also said that ‘monuments to white supremacy don’t belong in places of allegiance, and it’s past time that these painful memorials be moved in a legal, safe way.’ ”

Crews add The Henry Wyatt Monument to a truck after removing them from the North Carolina State Capitol in Raleigh, N.C., Saturday, June 20, 2020. (Ethan Hyman/The News & Observer via AP)

This update tells us two of the monuments have been removed. “Crews have removed two Confederate statues outside the North Carolina state capitol in Raleigh on order of the governor. The statues were taken away on Saturday, the morning after protesters toppled two nearby statues. Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper, who has long advocated removing the statues, said in a press release that removing the statues was a public-safety imperative. ‘If the legislature had repealed their 2015 law that puts up legal roadblocks to removal, we could have avoided the dangerous incidents of last night,’ Cooper said. One of the statues is dedicated to the women of the Confederacy. The other was placed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy honoring Henry Wyatt, the first North Carolinian killed in battle in the Civil War. Both statues stood for over a century. A 2015 law bars removal of the memorials without permission of a state historical commission. But Cooper said the law creates an exception for public-safety emergencies, and he is acting under that provision.”

This story tells us the movement followed the partial toppling of the third monument. “Crews have removed two Confederate monuments from downtown Raleigh, including the Daughters of the Confederacy Monument and the Henry Lawson Wyatt Monument. This follows the partial toppling of the Confederate monument outside the Capitol Friday evening. Protesters gathered outside the Capitol and took down parts of the monument with ropes. The statues were dragged on the street and one was hung on W. Hargett Street. In a statement Saturday, Gov. Roy Cooper said he has ordered all monuments on the Capitol grounds to be moved ‘to protect public safety.’ This includes the monument to the Women of the Confederacy, the figure of Henry Lawson Wyatt and the remainder of the North Carolina Confederate monument.

This story gives the historical background of the monuments.

Capitol Confederate soldier monument

“This 75-foot-tall statue was unveiled in 1895, around 30 years after the end of the Civil War. It has an interesting history of controversy, even dating back to its installment. The monument was controversial even when it was proposed, according to research compiled on a UNC Library site. At the time of its unveiling, ‘Populist and Republican leaders objected to any public funding of the monument on the grounds that public education, rather than sectional pride, was a pressing need.’ Another outcry occurred in the 1930s in response to the possibility of moving the monument off the Capitol Grounds and onto Nash Square. Raleigh’s citizens spoke out against ‘moving such a historically significant monument from such a highly visible location.’ When the monument was unveiled, Julia Jackson Christian, Granddaughter of famous Confederate General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, spoke at the event.”

Monument Dedicated to the North Carolina Women of the Confederacy

“Susanna Lee, an associate professor of history at North Carolina State University, says the Civil War monuments downtown are different than those built to memorialize individual soldiers in graveyards, several of which can be found just blocks away in Oakwood Cemetery. As political campaigns of white supremacy gained ground in North Carolina and across the country, memorials like those at the Capitol spread. This monument commemorated wives and daughters left behind in the south while men were left to fight in the Civil War. In the 1914 dedication of the monument, Daniel Harvey Hill praised the strength of Southern women who picked up the slack in the absence of their male counterparts, calling each home’s mistress ‘the greatest slave on the plantation which moved at her command.’ Women weren’t without aid, as Hill noted in his address at the dedication. He praised the ‘noble fidelity’ of the slaves who stayed with their owners and called it proof of ‘the kindly relations that existed between the white families and colored families on the plantation home’ – and often-repeated theme of the time. Lee said the women’s monument is interesting because of the debate about its design. Originally, plans depicted a woman and a little girl, who was eventually swapped out for a boy holding a sword. The final version reflected the traditional role for women in raising children with a sense of duty. ‘They don’t vote, but one of the ways they contributed to the nation was by creating good citizens,’ Lee said.”

A statue commemorating Confederate Gen. Albert Pike sits on the ground moments after protesters toppled it late Friday night in Washington, D.C. Eric Baradat/AFP via Getty Images

According to this story, the statue of confederate general Albert Pike took the plunge and had a pretty hot time in the nation’s capital. “Another Confederate monument has fallen — this time in a city where such memorials were understandably rare to begin with: the nation’s capital. Protesters on Friday night toppled a statue of Confederate Gen. Albert Pike, the only outdoor Confederate memorial in the city. They yanked it down with rope and later set it ablaze as law enforcement looked on. It was an abrupt end for a controversial monument, which has attracted criticism and often outright confusion from residents. Born in Massachusetts, the nativist attorney and author fought for the Confederacy and spent much of his time after the Civil War supporting the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. The international fraternal organization commissioned the statue in his honor around the turn of the 20th century. But, lately, even the Freemasons haven’t resisted calls to have it removed. Last year the District’s nonvoting congressional delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton, introduced legislation seeking its removal — which, due to D.C.’s unique position, requires federal approval. The bill has so far languished in the House.”

Historian Zac Cowsert expounded on Pike on Twitter. He wrote, “Yes, he was a Confederate general (a terrible one). But on the outset of the Civil War, Pike played a role in dragging several Native nations into the war. In 1861, Indian Territory (now OK) held the Five Tribes: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole. These tribes enjoyed limited sovereignty, were slaveowning, and deeply reliant upon U.S. money. The U.S. bounced at war’s start, leaving the Indians alone. Enter Albert Pike, a clever/pompous Arkansas lawyer who’s been appointed commissioner to the Five Tribes by the CSA. He’s represented several tribes legally before. Pike starts with the Cherokee, but is told to buzz off by Chief John Ross who prefers neutrality. Pike gets the Choctaw/Chickasaw on board with relative ease. These nations have powerful slaveholding interests. They also border Texas, and TX has made clear they should ally with the South…or else. Pike then proceeds to Creek Nation. The Creeks are deeply divided by the prospect of war. Nearly a 50/50 split. In fact, at the moment Pike arrives, several prominent pro-neutral Creeks are out of town trying to convince other Indians to stay out of the war at Antelope Hills. This isn’t luck…it’s planned. Pike knows many Creeks favor neutrality, but he also knows the political opposition is out of town. He brags about this later: ‘I defeated all that [neutrality] by treating with the Creeks at the very time that their delegates were at the Antelope Hills in council.’ So while the neutral Creeks are absent, Pike negotiates a treaty with pro-Confederate Creeks. He offers them a ‘sweet’ deal, including protection of slavery and representation in CS Congress. But you need the full tribe’s permission. When the neutral Creeks return, they balk. Pike simply cannot convince these neutral Creeks to sign the treaty. In fact, they walk out of the Creek National Council in protest. In what is to me fraud reminiscent of the 1820s/1830s, Pike and the pro-CS Creeks sign the treaty anyway. In fact, they add the names of a few walkouts to make the whole things seem more legit. To be clear, probably half the Creek tribe supported the CSA…but half did not. Those Creeks who didn’t felt the conflict a ‘white man’s war’ and feared the result. Having ‘negotiated’ with the Creeks, Pike essentially pulls the same play with the Seminoles, signing a Confederate treaty despite serious internal resistance. Rumors swirled (though never proven) Pike greased a few palms, too. Pike eventually gets the Cherokees to side with the CS (another story entirely). He gets rewarded with a brigadier’s star. But all of this backfires wildly on Pike and the CSA. The pro-neutral Creeks and Seminoles decide to resist, first politically then militarily. They reject the CS treaties, gathering under Creek chief Opothleyahola and mobilizing an army of perhaps 6,000. Included were Creeks, Seminoles, some 500 African-Americans (free and runaway), and others. They ask the U.S. for help (and of course don’t get it). In the winter of 1861, these ‘Loyal Indians’ fight a three battle campaign against the Confederacy and are ultimately driven into Kansan exile. In this campaign, Creeks fought Creeks, etc. Pike misses all this b/c he’s in Richmond wining and dining through the winter. In 1862, however, Pike’s military incompetence is revealed. Has no control of his men at Pea Ridge. Completely fails to protect Indian Territory from U.S. invasion/liberation. Feuds with his boss to the point of imprisonment. Resigns. To my understanding, he gets some postwar fame as a Freemason, who build the statue in #WashingtonDC that went down yesterday. But to me, Pike’s legacy is one of a fraudulent diplomat and bumbling military commander. Good riddance. Fin! Actually, if you want to know more, check out Clarissa Confer, Mary Jane Warde, W. Craig Gaines, Carolyn Ross Johnston, Lela McBride, and others I’m forgetting. Also…me (my dissertation)! Standard Pike bio is by Walter Brown (it’s a doorstopper).”

We have this story from Arkansas. It tells us, “A Confederate monument at the Jefferson County courthouse was removed on Saturday morning. According to Jefferson County Judge Gerald Robinson, it was a collaborative effort between him and the Daughters of the Confederacy Chapter. Judge Robinson said that an agreement was reached with a moving company who wants to remain anonymous to move the statue. ‘When we explained, we had some monetary pledges from private donors to help cover their costs, they agreed to proceed with the removal and give the Chapter time to pay for the unpaid balance. So we are still asking for more donations. We are still preserving the historical aspect of the monument and not destroying it,’ Robinson said. It will be moved to the Camp White Sulphur Spring Confederate Cemetery to uphold the value of the statue.”

This story tells us the University of Mississippi students who petitioned for removal of a confederate statue are now protesting the university’s plans to turn the new site of the statue into a travel destination. “In early 2019, we wrote the University of Mississippi’s Associated Student Body Senate resolution that ignited the relocation process for the campus’ Confederate monument. A year and a half later, the Institutions of Higher Learning Board approved a plan to relocate the statue to a secluded Confederate cemetery. However, the proposed relocation plan contradicts the University of Mississippi community’s priorities as reflected in resolutions passed through the university’s representative bodies and in the university’s creed. Within the proposal are plans to beautify the University Cemetery with new headstones, pavement, and enhanced lighting. Following these plans is a statement declaring that the proposal ‘received written endorsement from various campus constituencies.’ UM administration did not release the updated proposal to campus constituencies or the broader community before IHL approved the proposal. Therefore, the proposal was not ‘endorsed.’ These plans have since been widely and publicly rejected among students, faculty, and campus constituency groups. As the authors of the initial resolution, we strongly oppose any measures that would uplift white supremacist narratives or glorify the Confederacy. We urge the University of Mississippi administration to refrain from renovations of the cemetery that would amplify ahistorical and racist Confederate narratives. The unanimously passed resolution called for relocating the monument to a less prominent place on campus. We did not co-sign onto a project beautifying the Lost Cause. When we wrote the student resolution, we had two main goals—ridding the University of Mississippi of Confederate iconography that rallies neo-Confederates and fostering an environment that is welcoming and inclusive of all students, particularly Black students. The expanded glorification of Confederate symbols and ideologies, as presented in the university’s relocation proposal are inconsistent with the goals of the university community who set relocation into motion. The University of Mississippi should reject the glorification of white supremacist ideology. The proposed plan fails to do so, and we are concerned the university will continue to serve as a rallying point for hate groups and white supremacists. As an institution that relies on state tax dollars and private funding to provide a world-class education and unique student experiences, the allocation of funds towards the beautification and preservation of Confederate symbols detracts financial resources from continued educational efforts. It also violates the University’s Creed: ‘I believe in good stewardship of our resources,’ and signals to current and prospective faculty and students that Confederate glorification is a higher priority than their continued success.”

This story asks if we must allow symbols of racism on public land. It’s a Q&A with Professor Annette Gordon-Reed. In part of the interview we see:

“GAZETTE: What do you say to those who argue that the removal of such statues in prominent public settings dishonors the memory of those who died fighting for the Confederacy?

GORDON-REED: I would say there are other places for that — on battlefields and cemeteries. The Confederates lost the war, the rebellion. The victors, the thousands of soldiers — black and white — in the armed forces of the United States, died to protect this country. I think it dishonors them to celebrate the men who killed them and tried to kill off the American nation. The United States was far from perfect, but the values of the Confederacy, open and unrepentant white supremacy and total disregard for the humanity of black people, to the extent they still exist, have produced tragedy and discord. There is no path to a peaceful and prosperous country without challenging and rejecting that as a basis for our society.

GAZETTE: Many believe that taking the statues down is an attempt to cover up or erase history. Do you agree?

GORDON-REED: No. I don’t. History will still be taught. We will know who Robert E. Lee was. Who Jefferson Davis was. Who Frederick Douglass was. Who Abraham Lincoln was. There are far more dangerous threats to history. Defunding the humanities, cutting history classes and departments. Those are the real threats to history.

GAZETTE: In the past, people have suggested the monuments should stay, but that additional plaques or other information should be incorporated to add context. What do you think of that idea? What are your thoughts on a separate museum for such statues?

GORDON-REED: Plaques can work in some situations. It depends on who the person is and what the objections are. As for museums, people I know who work in museums tear their hair out about this suggestion, that somehow, we’re going to ship all these Confederate monuments off to the lucky museum that has to find a place to put them.

GAZETTE: What about the slippery slope argument? Many of America’s founders — George Washington, Thomas Jefferson — owned slaves. Does removing statues of Columbus or Confederate officials pave the way for action against monuments honoring those who helped create the United States?

GORDON-REED: I suppose, if people want to, everything can pave the way to some other point. I’ve said it before: There is an important difference between helping to create the United States and trying to destroy it. Both Washington and Jefferson were critical to the formation of the country and to the shaping of it in its early years. They are both excellent candidates for the kind of contextualization you alluded to. The Confederate statues were put up when they were put up [not just after the war but largely during periods of Civil Rights tension in the 20th century], to send a message about white supremacy, and to sentimentalize people who had actively fought to preserve the system of slavery. No one puts a monument up to Washington or Jefferson to promote slavery. The monuments go up because, without Washington, there likely would not have been an American nation. They put up monuments to T.J. because of the Declaration of Independence, which every group has used to make their place in American society. Or they go up because of T.J.’s views on separation of church and state and other values that we hold dear. I think on these two, Washington and Jefferson, in particular, you take the bitter with sweet. The main duty is not to hide the bitter parts.”

Another Confederate monument was vandalized in Richmond overnight. (Source: NBC12)

This story talks about vandalizing confederate statues in Libby Hill Park in Richmond, Virginia. “Another Confederate monument was vandalized in Richmond overnight. This time, it was the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Memorial in Libby Hill Park. The graffiti did not come as surprise as there was plenty of chatter on social media that it would be a target. A note left at the scene reads in part, ‘we do not come in peace…we come in war against the spiritual powers of oppression, greed, and injustice.’ Police have no suspects.”

In this story we find the First Virginia Regiment monument in Richmond took the plunge as well. “Another statue was torn down in Richmond this weekend. The statue atop the First Virginia Regiment Monument in Meadow Park in the Fan District was toppled from its pedestal. The park is at the intersection of Park Avenue, Meadow Street and Stuart Avenue in the Fan. It’s roughly a block away from the Lee statue on Monument Avenue. Tweets by VPM on Saturday morning showed the statue on the ground in the park. It was later taken away. It’s unclear when exactly the statue was torn down late Friday or early Saturday. This is the fifth statue taken down in Richmond during protests in recent weeks. Other statues torn down include Confederate president Jefferson Davis on Monument Avenue, Confederate Gen. Williams Carter Wickham in Monroe Park, Christopher Columbus in Byrd Park and the Richmond Howitzers Monument at the corner of Harrison Street and Grove Avenue. The First Virginia Regiment Monument is a memorial to a state militia regiment formed in 1754 before the Revolutionary War.” Some may argue this isn’t a confederate monument, but one would have to ask what service the unit performed in the Civil War, and what was their main function prior to the Civil War–being available to put down slave rebellions.

A statue of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson stands tall on the grounds of the West Virginia Capitol building in Charleston. Dave Mistich/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

We have this story about confederate monuments in West Virginia, a state that was born in the Civil War and sided with the United States. “One hundred fifty-seven years ago Saturday, West Virginia seceded from Virginia to join the Union and reject the Confederacy. Across the state, there are 21 statues and memorials honoring Confederate generals and soldiers, according to data compiled by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Like many monuments elsewhere, some of West Virginia’s were gifted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy during Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement. ‘We always need to remember that the monuments always reflect the values of the community — the individuals or organizations that erected them and dedicated them originally,’ says Boston-based historian Kevin Levin. ‘One way to measure the progress — if you want to call it that — is to look at the places that are even debating this issue,’ he says, noting that many of the efforts to remove statues are happening in urban areas with more diverse populations. Much of the conversation in West Virginia has focused on Thomas Jonathan ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, a Confederate general who was born in present-day West Virginia. Jackson, who owned six slaves, is memorialized in more than a dozen states and is one of the most recognizable figures of the Civil War. This week in West Virginia, the Harrison County Commission rejected a motion to remove a statue of Jackson that stands in front of the courthouse in downtown Clarksburg. In Charleston, a bust and statue of Jackson are on display on the grounds of the state Capitol. A middle school in the city, where nearly half the students are Black, also bears Jackson’s name. Discussions are ongoing about renaming the school after influential Black educator Booker T. Washington or NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson.”

The Harrison County Commission voted Wednesday, June 17 to reject a motion to remove a statue of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson. The statue, erected in 1953 as a gift from the United Daughters of the Confederacy, stands in front of the courthouse. Dave Mistich/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

According to the article, “Some who support memorials of Jackson argue that he should instead be judged by his deeds such as conducting Sunday School for enslaved Black people and encouraging literacy.” That’s a bit of a mischaracterization. It’s not clear that Jackson encouraged literacy for enslaved people, but he did encourage their learning what the Bible said. Professor James I. Robertson’s magisterial biography of Jackson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend doesn’t specifically say Jackson encouraged literacy or taught enslaved people to read or write. It’s clear Jackson led the school and commented on Bible passages, but there is no clear evidence there that enslaved people were taught to read or write. The article continues, “The American Civil War Museum has said these facts serve as ‘a foundation for great misunderstanding’ in allowing Confederate heritage activists to distance the South’s cause away from slavery. West Virginia native and a professor of History at the College of Southern Maryland, Cicero Fain, also says considering figures like Jackson for their good deeds overlooks a fundamental question in the current debate over the monuments. ‘The barometer by which one should judge a slaveholder is ‘Did he make the ultimate sacrifice and a shift away from the economic imperative — and instead embrace a moral imperative?’ And he didn’t,’ Fain says. Republican Gov. Jim Justice said this week the memorials at the state Capitol are an issue for the Legislature to decide but avoided saying whether he wants to see them taken down. ‘From the standpoint of my personal beliefs, I don’t feel like — that — anyone should feel uncomfortable here. This is our capital. This is our state. This is our people,’ he said a news briefing Wednesday. But state code gives the authority to decide the fate of the statues on the Capitol grounds to a commission, which is partially appointed by the governor.”

Historian Rebecca Toy has this blog post regarding the Lee monument. She writes, “Very few of us who study the Civil War (probably more accurately, none of us) have not had a conversation with someone concerned that taking monuments down was ‘rewriting history’ or ‘white-washing history.’ Of course, history reminds us that these monuments themselves white-washed history and told a story that was often far more glorious than reality. For evidence of this, consider the Jefferson Davis monument down the road from Lee, which reads, ‘DEFENDER OF THE RIGHTS OF STATES’ and fails to specify that the right to enslave other human beings was the principle right Davis defended by leading the Confederacy in secession. … Whatever you might think about whether these monuments are ‘history,’ we must also consider that the United States has long enacted democracy on the ground. As the U.S. built the infrastructure of a nation – cities, highways, National Parks – its designers did so with a belief that we could inscribe the heart of the American nation onto its physical landscape. In the words of planners who designed the National Mall, who picked out the first National Parks, and who created national monuments, we find this sentiment repeated over and over again. These physical objects and spaces could, and should, represent us. Yes, that included representing historical figures and ‘telling’ history. But there has always been more to it. We chose those figures, and we tell those stories, because we believe they can do important work in the present. Those who designed and dedicated the Lee monument in Richmond knew this and acknowledged it. Speaking at the dedication of the Lee monument in 1890, Archer Anderson, a former Confederate staff officer, proclaimed, ‘Fellow citizens, a people carves its own image in the monuments of its great men. Not Virginians only, not only those who dwell in the fair land stretching from the Potomac to the Rio Grande, but all who bear the American name may proudly consent that posterity shall judge them by the structure, which we are here to dedicate and crown with a heroic figure…Let this monument, then, teach to generations yet unborn these lessons of his life!’ The monument’s creators believed that this image was not just of Lee, but of the people now dedicating it. It was an image, said Anderson, not just of Lee, not just of Virginians, but of all Americans ‘from the Potomac to the Rio Grande.’ Moreover, the monument would teach ‘generations yet unborn,’ not about who Lee was, but ‘lessons of his life.’ John Mitchell, Jr. editor of the Richmond Planet and a Black Richmond city council member, explained there was no mistaking what those ‘lessons’ of Lee’s life were at the monument’s dedication. Describing the scene, Mitchell wrote, ‘Rebel flags were everywhere displayed and the long lines of Confederate veterans who embraced the opportunity and attended the reunion to join again in the ‘rebel yell’ told in no uncertain tones that they still clung to theories which were presumably buried for all eternity.’ They may have lost the war, but these former Confederates were not giving up the vision of the nation their war was meant to create. Instead of leaving the United States, they would etch that vision into its landscape. Speaking in 1890, Anderson was in many ways foreshadowing what was coming as white Virginians beat back the successes of Reconstruction and Black political enfranchisement and solidified elite white men’s control over the government. We believe public spaces and public objects, like monuments, can move the nation. Said differently: they are political. They do political work. Think for a minute about your school field trips to places like the National Mall, in Washington, D.C. or the local National Park. What was it they wanted you to learn? What did you feel as you took it in? How did your teachers frame your visits? They wanted to teach you something, not just about the past, but about the present and the future. Look no further than the ‘history’ page of the National Mall’s website, which reads, ‘The sites of National Mall and Memorial Parks are a testament to America’s past and present where the values of our nation are presented.’ These spaces, and the monuments that inhabit them, present the nation. With this in mind, I hope we can all agree that if these public spaces are meant to inscribe the American nation onto its physical landscape, if they are about articulating to viewers who we are and what we are about, then change can be good. Change is good. Change is a reflection of our desire to create a democracy where everyone’s voice is heard, acknowledged, and valued. And change is needed, because who we were as a nation when these particular monuments went up at the turn of the twentieth century is not who we want to be anymore. If we start looking around, we’ll probably notice other public spaces that need revision too. Not because we want to ‘rewrite’ the past or overwrite history, but because these spaces are about us here and now and what we want our future to look like. That is what they have always been about, and again, I hope we can agree that the nation we looked to become during the glory days of monument construction (read: the late nineteenth and early twentieth century) is not who we hope to be now.”

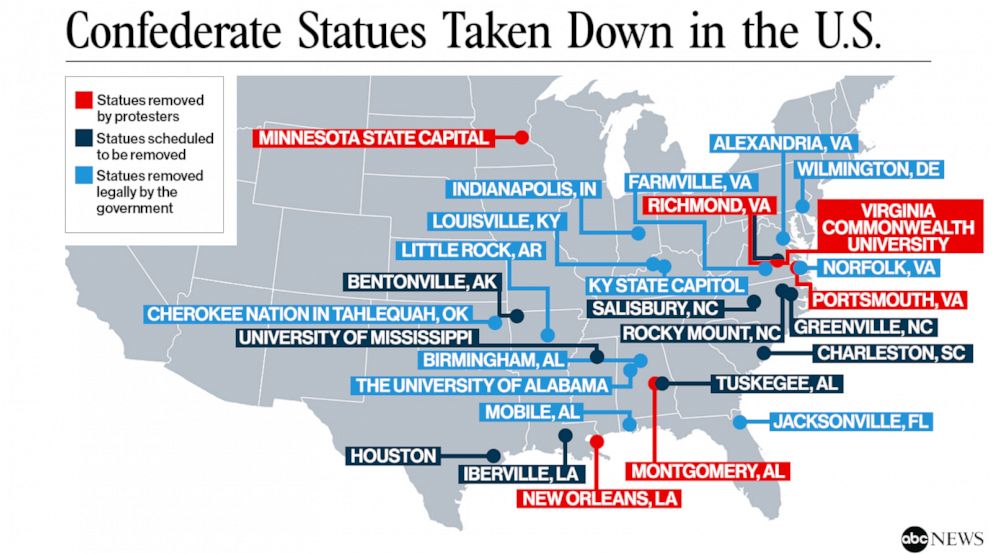

Confederate Statues Taken Down in the U.S.Confederate Statues Taken Down in the U.S. ABC NEWS

This story seeks to give us a snapshot of where confederate monuments left their positions. It’s already outdated. This story also seeks to recap monument removal and where monuments remain, but it, too, is already outdated.

In a Civil War- and monument-related action, protesters in San Francisco tore down a Ulysses S. Grant statue due to his past as a slave owner. This article tells us, “While Grant is widely celebrated as being one of the leading forces who helped the Union win the Civil War, bringing an end to slavery in the U.S., some historians have pointed to his complicated relationship with slavery. ‘Grant did in fact own a man named William Jones for about a year on the eve of the Civil War,’ Sean Kane, interpretations and programs specialist at the American Civil War Museum, said in an article. ‘In 1859, Grant either bought or was given the 35-year-old Jones, who was in Grant’s service until he freed him before the start of the War.’ Kane also noted that Grant married into a slaveholding family that owned dozens of slaves. After Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, Grant wrote his father, an abolitionist, saying, ‘My inclination is to whip the rebellion into submission, preserving all Constitutional rights. If it cannot be whipped any other way than through a war against slavery, let it come to that legitimately. If it is necessary that slavery should fall that the Republic may continue its existence, let slavery go.’ ”

This article goes into Grant’s actions as President of the United States against the KKK. Contrary to what the article asserts, Nathan Bedford Forrest was not a founder of the KKK. The article says, “History reported that the KKK terrorized blacks and Republicans in the South during the era of Reconstruction: ‘Most prominent in counties where the races were relatively balanced, the KKK engaged in terrorist raids against African Americans and white Republicans at night, employing intimidation, destruction of property, assault, and murder to achieve its aims and influence upcoming elections. In a few Southern states, Republicans organized militia units to break up the Klan. In 1871, passage of the Ku Klux Act led to nine South Carolina counties being placed under martial law and thousands of arrests. In 1882, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Ku Klux Act unconstitutional, but by that time Reconstruction had ended, and much of the KKK had faded away.’ Congress responded to the violence by passing a series of bills that allowed Grant to use military force to protect the rights of blacks. ‘The Third Force Act, also known as the KKK or the Civil Rights Act of 1871, empowered President Ulysses S. Grant to use the armed forces to combat those who conspired to deny equal protection of the laws and, if necessary, to suspend habeas corpus to enforce the act,’ Politico reported. ‘Grant signed the legislation on this day in 1871. After the act’s passage, the president for the first time had the power to suppress state disorders on his own initiative and suspend the right of habeas corpus. Grant did not hesitate to use this authority.’ Politico added, ‘Shortly after Congress approved the law, nine counties in South Carolina, where KKK terrorism was rampant, were placed under martial law and thousands of persons were arrested.’ ”

This article also quotes the Kane article from the ACWM. We learn, ” ‘Grant may have been initially ambivalent to the institution of slavery,’ Kane wrote on the civil war museum’s website, ‘but his wartime experiences showed him that it was morally and practically indefensible and that African Americans would not only make strong allies in defeating the Confederates, but respected citizens in the reunited nation to follow. As the 18th President of the reunited nation, he was an advocate and defender of the freedmen’s newly acquired rights…In his memoirs Grant wrote, ‘As time passes, people, even of the South, will begin to wonder how it was possible that their ancestors ever fought for or justified institutions which acknowledged the right of property in man.’ ‘ ”

This article from Nick Sacco explores William Jones, the enslaved man Grant briefly owned and then freed. Those interested in Grant’s relationship with Native Americans can see this story to start.

I think this provides us an opportunity to talk about which statues may be considered to be restored, and to open a dialogue about Grant and his legacy. Ultimately, it will [and should] be up to the people of San Francisco to determine if they want Grant restored to the pedestal or not.

Finally, here is an excellent discussion between Kevin Levin and Professor Hilary Green on how we remember and memorialize the Civil War, including monuments. This discussion was under the auspices of Ford’s Theatre.

Got it all in.

At the University of Oregon, where I got my Ph.D, last weekend students ripped down statues known as the “Pioneer Father” and “Pioneer Mother” which have long been controversial, and were recently recommended for removal by a colleague of mine who studied the context of their creation in 1919 and found that yes (big shocker) it was racist. The statues were not only torn down, they were dragged through the main street of campus, symbolically like bodies of African-Americans have been dragged during lynchings, and left in front of the steps to the university president’s office. Virtually the whole campus, except the president, applauded the move. He issued a mealy-mouthed statement lamenting that the teardown meant we couldn’t have six months of “dialogue” and committee studies before he ultimately decided to leave the statues where they were, which is exactly what would have happened. So it’s not just about Confederates.

The laws prohibiting the removal of statues are becoming increasingly irrelevant. As you point out here, most can be overridden by a public safety exception. But for even those that can’t, direct action like what happened at University of Oregon cuts through all the chaff. Committee studies and administrative processes for statue removal just aren’t realistic anymore. I think statues will continue to come down, and I think the judgments made so far on the ones that need to go have been pretty sound. Thanks for all your reporting on this.

Thanks for your perspective, Sean. True, it’s not all about confederates. Colonizers are also targets for what happened with the Indian population. Now that the statues in Oregon are down, nothing prevents a dialogue about them from opening up and talking about whether or not they should be restored, so the university president, if he doesn’t ope a dialogue, would be shown to be a bit disingenuous in his statement. I think a streamlined administrative process can work. Reaching a threshold of signatures on a petition for removal automatically triggers moving the monument to a safe location and opening a dialogue. If the community decides to keep the monument, it gets returned. If not, then they’ve averted a possible injury from people tearing it down. But we need to get rid of those heritage laws. As John F. Kennedy once said, if you make peaceful revolution impossible, you make violent revolution inevitable.