NY Times Photo

The rhetorical battle over the New York Times’s “1619 Project” continues unabated. The eminent historian Victoria Bynum details her objections in her blog post here. She says, “After reframing the meaning of the American Revolution, [Nicole] Hannah-Jones moves on to the Civil War and Reconstruction, barely touching on American abolitionism and ignoring the free soil movement, though both were seeds of the antislavery Republican Party. In discussing the nation’s wrenching effort to reconstruct itself after the Civil War, she asserts that ‘blacks worked for the most part . . . alone’ to free themselves and push for full rights of citizenship through passage of the Reconstruction Amendments. Rightly emphasizing the vigilante white violence that immediately followed the victories of a Republican-dominated Congress, she ignores important exceptions, including the Southern white ‘Scalawags,’ many of whom were nonslaveholders who fought against the Confederacy in the war and participated with blacks and Northern Republicans in passing the Reconstruction Amendments.” She continues, “To be sure, Southern whites were among the most conservative members of the Republican Party. Nonetheless, important legislation was passed with their participation, enabling the United States by 1868 to begin building a more racially just, democratic society before white supremacist Democrats derailed Reconstruction. Furthermore, not only does Hannah-Jones ignore the Scalawags, but also Matthew Desmond, in his essay on capitalism and slavery, ignores nonslaveholding propertied farmers, the largest class of whites in the antebellum South, and from which many Southern Republicans emerged.” That’s not the only factor Professor Bynum identifies. “Likewise, the 1619 Project ignores late 19th and 20th century interracial efforts to combat the power of corporations by an emergent industrial working class. Instead of studying the methods by which industry destroyed such efforts by fomenting racism, the project continues to argue that blacks struggled ‘almost alone’ in a world where an undifferentiated class of whites controlled the levers of power. Thus, some of our nation’s greatest historical moments of interracial class solidarity, the labor struggles shared by working class people across the color line, are erased. For example, the Populist Movement is barely mentioned, the early 20th century Socialist Movement, not at all. And, although Jesse Jackson’s rousing Rainbow Coalition speech at the Democratic Convention of 1984 is remembered favorably by one project author, the small farmers, poor people, and working mothers that Jackson included alongside African Americans, Arab Americans, Hispanic Americans, and gay and lesbian people are ignored. Multiracial communities are also passed over by the 1619 Project. Yet, race-mixing among Africans, Europeans, and American Indians early on presented British colonists with a dilemma—how to maintain the image of race-based slavery while increasing their labor force by enslaving people of partially white ancestry. The essentialist one drop rule, based on a theory of hypodescent, eventually provided the solution. Simply put, African blood was decreed so powerful (or polluting) that a mere fraction of African ancestry was enough to render a person ‘black,’ no matter how white that person’s appearance. Hannah-Jones herself recognizes the fallacy of ‘race’ when she writes that ‘enslavement and subjugation became the natural station of people who had any discernible drop of ‘black’ blood (italics mine).‘ The 1619 Project makes no attempt, however, to explore connections between race mixing and the class history of the United States. But make no mistake. The Southern slaveholding class knew that the one drop rule was a game of semantics. Slavery was first and foremost a closed labor system. Racism provided the rationale. Between 1855 and 1860, prominent proslavery author George Fitzhugh had no difficulty urging the United States to merge its systems of class and race by enslaving lower-class whites as well as people of color.” Professor Bynum concludes, “The 1619 Project claims to be a long overdue contribution to understanding slavery and racism over the course of 400 years of American history. It includes literary works of poetry, fiction, and memory that are revelatory and moving. They and many of the short research pieces evoke sadness, outrage, and anger. But they are not well served by the larger project, which sweeps over vast chunks of innovative and ground breaking historiography to tell a story of relentless white-on-black violence and exploitation that offers no hope of reconciliation for the nation. The project’s great flaw is its lack of solid grounding in the history of European colonization, the American Revolution, the American Civil War, and racial and class relations throughout. History is a profession that takes years of training. In his response to our letter to the New York Times, editor Jake Silverstein admits that, although the Times consulted with scholars, and although Nikole Hannah-Jones ‘has consistently used history to inform her journalism.’ . . . . the newspaper ‘did not assemble a formal panel [of historians] for this project.’ Perhaps this explains why a number of 1619 Project defenders, including Hannah-Jones, implicitly deny the need for training by claiming there is no such thing as objective history anyway. Too often, the assumption that journalists make good historians leaves us fighting over dueling narratives about the past based on political agendas of the present.” That is absolutely true.

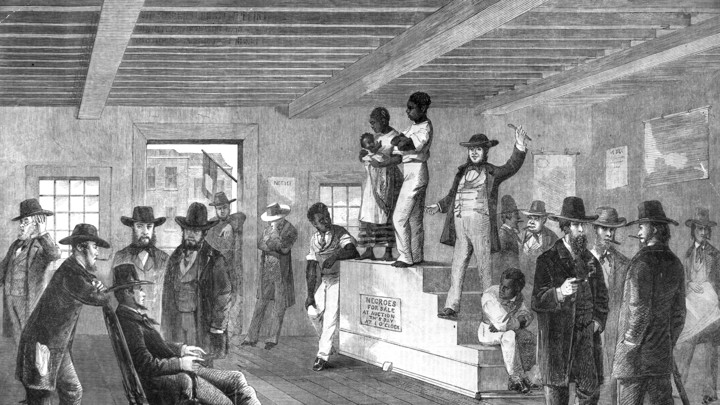

From the article. BETTMANN / GETTY

One vigorous defender of the project is the journalist Adam Serwer. In this article for The Atlantic he responds to the criticisms the five historians wrote. He says, “Several weeks ago, the Princeton historian Sean Wilentz, who had criticized the 1619 Project’s ‘cynicism‘ in a lecture in November, began quietly circulating a letter objecting to the project, and some of Hannah-Jones’s work in particular. The letter acquired four signatories—James McPherson, Gordon Wood, Victoria Bynum, and James Oakes, all leading scholars in their field. They sent their letter to three top Times editors and the publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, on December 4. A version of that letter was published on Friday, along with a detailed rebuttal from Jake Silverstein, the editor of the Times Magazine. The letter sent to the Times says, ‘We applaud all efforts to address the foundational centrality of slavery and racism to our history,’ but then veers into harsh criticism of the 1619 Project. The letter refers to ‘matters of verifiable fact’ that ‘cannot be described as interpretation or ‘framing’’ and says the project reflected ‘a displacement of historical understanding by ideology.’ Wilentz and his fellow signatories didn’t just dispute the Times Magazine’s interpretation of past events, but demanded corrections.” He continues, “Nevertheless, some historians who declined to sign the letter wondered whether the letter was intended less to resolve factual disputes than to discredit laymen who had challenged an interpretation of American national identity that is cherished by liberals and conservatives alike. ‘I think had any of the scholars who signed the letter contacted me or contacted the Times with concerns [before sending the letter], we would’ve taken those concerns very seriously,’ Hannah-Jones said. ‘And instead there was kind of a campaign to kind of get people to sign on to a letter that was attempting really to discredit the entire project without having had a conversation.’ ” I have to say that sounds more than a bit disingenuous to me. The Times certainly didn’t contact these historians, who are at the top of the profession, for their comments prior to publishing. It seems to me they aren’t owed the courtesy they failed to show themselves. Also, given the reaction I’ve seen from Ms. Hannah-Jones and the defenders of the project, I have no confidence at all their concerns would have been taken seriously at all. Mr. Serwer writes, “Underlying each of the disagreements in the letter is not just a matter of historical fact but a conflict about whether Americans, from the Founders to the present day, are committed to the ideals they claim to revere. And while some of the critiques can be answered with historical fact, others are questions of interpretation grounded in perspective and experience. In fact, the harshness of the Wilentz letter may obscure the extent to which its authors and the creators of the 1619 Project share a broad historical vision. Both sides agree, as many of the project’s right-wing critics do not, that slavery’s legacy still shapes American life—an argument that is less radical than it may appear at first glance. If you think anti-black racism still shapes American society, then you are in agreement with the thrust of the 1619 Project, though not necessarily with all of its individual arguments. The clash between the Times authors and their historian critics represents a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society. Was America founded as a slavocracy, and are current racial inequities the natural outgrowth of that? Or was America conceived in liberty, a nation haltingly redeeming itself through its founding principles? These are not simple questions to answer, because the nation’s pro-slavery and anti-slavery tendencies are so closely intertwined.” Mr. Serwer tells us, “The letter is rooted in a vision of American history as a slow, uncertain march toward a more perfect union. The 1619 Project, and Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay in particular, offer a darker vision of the nation, in which Americans have made less progress than they think, and in which black people continue to struggle indefinitely for rights they may never fully realize. Inherent in that vision is a kind of pessimism, not about black struggle but about the sincerity and viability of white anti-racism. It is a harsh verdict, and one of the reasons the 1619 Project has provoked pointed criticism alongside praise. Americans need to believe that, as Martin Luther King Jr. said, the arc of history bends toward justice. And they are rarely kind to those who question whether it does.”

Mr. Serwer writes, “Most Americans still learn very little about the lives of the enslaved, or how the struggle over slavery shaped a young nation. Last year, the Southern Poverty Law Center found that few American high-school students know that slavery was the cause of the Civil War, that the Constitution protected slavery without explicitly mentioning it, or that ending slavery required a constitutional amendment. ‘The biggest obstacle to teaching slavery effectively in America is the deep, abiding American need to conceive of and understand our history as ‘progress,’ as the story of a people and a nation that always sought the improvement of mankind, the advancement of liberty and justice, the broadening of pursuits of happiness for all,’ the Yale historian David Blight wrote in the introduction to the report. ‘While there are many real threads to this story—about immigration, about our creeds and ideologies, and about race and emancipation and civil rights, there is also the broad, untidy underside.’ In conjunction with the Pulitzer Center, the Times has produced educational materials based on the 1619 Project for students—one of the reasons Wilentz told me he and his colleagues wrote the letter. But the materials are intended to enhance traditional curricula, not replace them. ‘I think that there is a misunderstanding that this curriculum is meant to replace all of U.S. history,’ Silverstein told me. ‘It’s being used as supplementary material for teaching American history.’ Given the state of American education on slavery, some kind of adjustment is sorely needed. Published 400 years after the first Africans were brought to in Virginia, the project asked readers to consider ‘what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year.’ The special issue of the Times Magazine included essays from the Princeton historian Kevin Kruse, who argued that sprawl in Atlanta is a consequence of segregation and white flight; the Times columnist Jamelle Bouie, who posited that American countermajoritarianism was shaped by pro-slavery politicians seeking to preserve the peculiar institution; and the journalist Linda Villarosa, who traced racist stereotypes about higher pain tolerance in black people from the 18th century to the present day. The articles that drew the most attention and criticism, though, were Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay chronlicling black Americans’ struggle to ‘make democracy real’ and the sociologist Matthew Desmond’s essay linking the crueler aspects of American capitalism to the labor practices that arose under slavery.”

At this point, about halfway through the article, Mr. Serwer first takes on one actual point the historians made. “The letter disputes a passage in Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay, which lauds the contributions of black people to making America a full democracy and says that ‘one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery’ as abolitionist sentiment began rising in Britain. This argument is explosive. From abolition to the civil-rights movement, activists have reached back to the rhetoric and documents of the founding era to present their claims to equal citizenship as consonant with the American tradition. The Wilentz letter contends that the 1619 Project’s argument concedes too much to slavery’s defenders, likening it to South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun’s assertion that ‘there is not a word of truth’ in the Declaration of Independence’s famous phrase that ‘all men are created equal.’ Where Wilentz and his colleagues see the rising anti-slavery movement in the colonies and its influence on the Revolution as a radical break from millennia in which human slavery was accepted around the world, Hannah-Jones’ essay outlines how the ideology of white supremacy that sustained slavery still endures today. ‘To teach children that the American Revolution was fought in part to secure slavery would be giving a fundamental misunderstanding not only of what the American Revolution was all about but what America stood for and has stood for since the Founding,’ Wilentz told me. Anti-slavery ideology was a ‘very new thing in the world in the 18th century,’ he said, and ‘there was more anti-slavery activity in the colonies than in Britain.’ Hannah-Jones hasn’t budged from her conviction that slavery helped fuel the Revolution. ‘I do still back up that claim,’ she told me last week—before Silverstein’s rebuttal was published—although she says she phrased it too strongly in her essay, in a way that might mislead readers into thinking that support for slavery was universal. ‘I think someone reading that would assume that this was the case: all 13 colonies and most people involved. And I accept that criticism, for sure.’ She said that as the 1619 Project is expanded into a history curriculum and published in book form, the text will be changed to make sure claims are properly contextualized. On this question, the critics of the 1619 Project are on firm ground. Although some southern slave owners likely were fighting the British to preserve slavery, as Silverstein writes in his rebuttal, the Revolution was kindled in New England, where prewar anti-slavery sentiment was strongest. Early patriots like James Otis, John Adams, and Thomas Paine were opposed to slavery, and the Revolution helped fuel abolitionism in the North. Historians who are in neither Wilentz’s camp nor the 1619 Project’s say both have a point. ‘I do not agree that the American Revolution was just a slaveholders’ rebellion,’ Manisha Sinha, a history professor at the University of Connecticut and the author of The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, told me.* ‘But also understand that the original Constitution did give some ironclad protections to slavery without mentioning it.’ ” Professor Sinha is absolutely right. While Ms. Hannah-Jones has finally recognized what she actually wrote wasn’t correct, I think she’s hedging a little bit to not forthrightly say to the historians, “You’re right and I was wrong.”

Mr. Serwer then brings in the right-wing critiques. “The most radical thread in the 1619 Project is not its contention that slavery’s legacy continues to shape American institutions; it’s the authors’ pessimism that a majority of white people will abandon racism and work with black Americans toward a more perfect union. Every essay tracing racial injustice from slavery to the present day speaks to the endurance of racial caste. And it is this profound pessimism about white America that many of the 1619 Project’s critics find most galling. Newt Gingrich called the 1619 Project a ‘lie,’ arguing that ‘there were several hundred thousand white Americans who died in the Civil War in order to free the slaves.’ In City Journal, the historian Allen Guelzo dismissed the Times Magazine project as a ‘conspiracy theory’ developed from the ‘chair of ultimate cultural privilege in America, because in no human society has an enslaved people suddenly found itself vaulted into positions of such privilege, and with the consent—even the approbation—of those who were once the enslavers.’ The conservative pundit Erick Erickson went so far as to accuse the Times of adopting ‘the Neo-Confederate world view’ that the ‘South actually won the Civil War by weaving itself into the fabric of post war society so it can then discredit the entire American enterprise.’ Erickson’s bizarre sleight of hand turns the 1619 Project’s criticism of ongoing racial injustice into a brief for white supremacy.” I think that’s a misstatement of what Mr. Erickson was getting at. Also, I don’t think he took the time to digest and properly evaluate what Professor Guelzo was saying. Mr. Serwer continues, “The project’s pessimism has drawn criticism from the left as well as the right. Hannah-Jones’s contention that ‘anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country’ drew a rebuke from James Oakes, one of the Wilentz letter’s signatories. In an interview with the World Socialist Web Site, Oakes said, ‘The function of those tropes is to deny change over time … The worst thing about it is that it leads to political paralysis. It’s always been here. There’s nothing we can do to get out of it. If it’s the DNA, there’s nothing you can do. What do you do? Alter your DNA?’ These are objections not to misstatements of historical fact, but to the argument that anti-black racism is a more intractable problem than most Americans are willing to admit. A major theme of the 1619 Project is that the progress that has been made has been fragile and reversible—and has been achieved in spite of the nation’s true founding principles, lofty ideals in which few Americans truly believe. Chances are, what you think of the 1619 Project depends on whether you believe someone might reasonably come to such a despairing conclusion—whether you agree with it or not.” I think this misses the point of Professor Oakes’s criticism and ignores the highly substantive criticisms Professor Oakes made about what was claimed regarding slavery from a factual basis. He’s making the point in this excerpt that much of the history of African Americans, such as the Great Migration, industrialization, and progress made in race relations are ignored in the claim that it’s “in the very DNA of this country.” One of the fundamental tenets of historical thinking is the recognition of change over time, something the project purporting to be a historical examination is ignoring in this case.

Mr. Serwer admits, “Although the letter writers deny that their objections are merely matters of ‘interpretation or ‘framing,’’ the question of whether black Americans have fought their freedom struggles ‘largely alone,’ as Hannah-Jones put it in her essay, is subject to vigorous debate. Viewed through the lens of major historical events—from anti-slavery Quakers organizing boycotts of goods produced through slave labor, to abolitionists springing fugitive slaves from prison, to union workers massing at the March on Washington—the struggle for black freedom has been an interracial struggle. Frederick Douglass had William Garrison; W. E. B. Du Bois had Moorfield Storey; Martin Luther King Jr. had Stanley Levison. ‘The fight for black freedom is a universal fight; it’s a fight for everyone. In the end, it affected the fight for women’s rights—everything. That’s the glory of it,’ Wilentz told me. ‘To minimize that in any way is, I think, bad for understanding the radical tradition in America.’ ” But then he goes on to say, “But looking back to the long stretches of night before the light of dawn broke—the centuries of slavery and the century of Jim Crow that followed—’largely alone’ seems more than defensible. Douglass had Garrison, but the onetime Maryland slave had to go north to find him. The millions who continued to labor in bondage until 1865 struggled, survived, and resisted far from the welcoming arms of northern abolitionists. ‘I think one would be very hard-pressed to look at the factual record from 1619 to the present of the black freedom movement and come away with any conclusion other than that most of the time, black people did not have a lot of allies in that movement,’ Hannah-Jones told me. ‘It is not saying that black people only fought alone. It is saying that most of the time we did.’ ” Now, I don’t wish to minimize the struggle of African Americans in courageously fighting to free themselves, from those who ran away from their enslavement to those who fought in the USCT to those who stood up to the KKK and other terrorist groups during Reconstruction to those who made their place in a Jim Crow society; however, they did have significant allies among whites who sought to make this country live up to its “all men are created equal” credo. I’m talking about the likes of Anthony Benezet, Elijah Lovejoy, Owen Lovejoy, Thaddeus Stevens, the Grimke Sisters, Elizabeth Van Lew, Henry Ward Beecher, John Brown, and Abraham Lincoln, to name just a few. To leave them out is just as inaccurate and demeaning as leaving out what African Americans did for themselves.

At this point, Mr. Serwer stops looking at the actual objections of the historians and starts to attack the letter. “Nell Irvin Painter, a professor emeritus of history at Princeton who was asked to sign the letter, had objected to the 1619 Project’s portrayal of the arrival of African laborers in 1619 as slaves. The 1619 Project was not history ‘as I would write it,’ Painter told me. But she still declined to sign the Wilentz letter. ‘I felt that if I signed on to that, I would be signing on to the white guy’s attack of something that has given a lot of black journalists and writers a chance to speak up in a really big way. So I support the 1619 Project as kind of a cultural event,’ Painter said. ‘For Sean and his colleagues, true history is how they would write it. And I feel like he was asking me to choose sides, and my side is 1619’s side, not his side, in a world in which there are only those two sides.’ This was a recurrent theme among historians I spoke with who had seen the letter but declined to sign it. While they may have agreed with some of the factual objections in the letter or had other reservations of their own, several told me they thought the letter was an unnecessary escalation. ‘The tone to me rather suggested a deep-seated concern about the project. And by that I mean the version of history the project offered. The deep-seated concern is that placing the enslavement of black people and white supremacy at the forefront of a project somehow diminishes American history,’ Thavolia Glymph, a history professor at Duke who was asked to sign the letter, told me. ‘Maybe some of their factual criticisms are correct. But they’ve set a tone that makes it hard to deal with that.’ ‘I don’t think they think they’re trying to discredit the project,’ Painter said. ‘They think they’re trying to fix the project, the way that only they know how.’ ” I think Professor Painter is absolutely right about this, and Professor Glymph agrees with factual criticisms but disagrees with what she sees as the letter’s tone. My concern is over factual inaccuracies as well.

Mr. Serwer then writes, “Historical interpretations are often contested, and those debates often reflect the perspective of the participants. To this day, the pro-Confederate ‘Lost Cause’ intepretation of history shapes the mistaken perception that slavery was not the catalyst for the Civil War. For decades, a group of white historians known as the Dunning School, after the Columbia University historian William Archibald Dunning, portrayed Reconstruction as a tragic period of, in his words, the ‘scandalous misrule of the carpet-baggers and negroes,’ brought on by the misguided enfranchisement of black men. As the historian Eric Foner has written, the Dunning School and its interpretation of Reconstruction helped provide moral and historical cover for the Jim Crow system. In Black Reconstruction in America, W. E. B. Du Bois challenged the consensus of ‘white historians’ who ‘ascribed the faults and failures of Reconstruction to Negro ignorance and corruption,’ and offered what is now considered a more reliable account of the era as an imperfect but noble effort to build a multiracial democracy in the South. To Wilentz, the failures of earlier scholarship don’t illustrate the danger of a monochromatic group of historians writing about the American past, but rather the risk that ideologues can hijack the narrative. ‘[It was] when the southern racists took over the historical profession that things changed, and W. E. B. Du Bois fought a very, very courageous fight against all of that,’ Wilentz told me. The Dunning School, he said, was ‘not a white point of view; it’s a southern, racist point of view.’ In the letter, Wilentz portrays the authors of the 1619 Project as ideologues as well. He implies—apparently based on a combative but ambiguous exchange between Hannah-Jones and the writer Wesley Yang on Twitter—that she had discounted objections raised by ‘white historians’ since publication. Hannah-Jones told me she was misinterpreted. ‘I rely heavily on the scholarship of historians no matter what race, and I would never discount the work of any historian because that person is white or any other race,’ she told me. ‘I did respond to someone who was saying white scholars were afraid, and I think my point was that history is not objective. And that people who write history are not simply objective arbiters of facts, and that white scholars are no more objective than any other scholars, and that they can object to the framing and we can object to their framing as well.’ When I asked Wilentz about Hannah-Jones’s clarification, he was dismissive. ‘Fact and objectivity are the foundation of both honest journalism and honest history. And so to dismiss it, to say, ‘No, I’m not really talking about whites’—well, she did, and then she takes it back in those tweets and then says it’s about the inability of anybody to write objective history. That’s objectionable too,’ Wilentz told me.”

Let’s take a closer look at this controversy. The exchange happened in November of 2019. Here’s a small portion:

I think that’s enough to judge for yourself if Ms. Hannah-Jones was misinterpreted.

Max Eden is a senior fellow in education policy at the conservative Manhattan Institute in New York City. He contributes this article opposing the project. He writes, “In 1858, Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln debated the nature of America’s soul. Douglas argued that the Founders believed that the claim in the Declaration of Independence—’all men are created equal’—applied only to whites. They were indifferent to the perpetuation of slavery, he said. Lincoln argued that the Founders foresaw an end to slavery, that the words in the Declaration meant what they said, and that no one before Douglas had ever suggested otherwise. After a bloody civil war and a decades-long civil rights struggle were fought to vindicate Lincoln’s position, the New York Times and the Pulitzer Center are urging teachers, with the 1619 Project and attendant K-12 curriculum, to take Douglas’s side of the argument. In her lead essay announcing the project, Nikole Hannah-Jones argues, per Douglas, that the ‘white men who drafted those words [in the Declaration] did not believe them to be true for the hundreds of thousands of black people in their midst.’ Hannah-Jones’s essay has come under withering attack from eminent historians such as Gordon Wood and James McPherson for its historical distortions. But the 1619 Project’s curriculum does more than encourage teachers to ignore key elements of the historical record; it asks students to blot them out.” Well, those words were written by Thomas Jefferson, who held hundreds of African Americans, including those who might well be his own children, in slavery. So it seems Ms. Hannah-Jones is correct about that. Mr. Eden is wrong about the Civil War being fought to vindicate Lincoln’s position. The United States wasn’t fighting to give equal rights to African Americans, although the Radical Republicans did their best to do so during Reconstruction. Mr. Eden continues, “One recommended ‘activity to extend student engagement’ asks teachers to lead students in transforming historical documents through ‘erasure poetry,’ which, the curriculum explains, ‘can be a way of reclaiming and reshaping historical documents; they can lay bare the real purpose of the document or transform it into something wholly new. How will you highlight inequity—or envision liberation—through your erasure poem?’ Students could, the guide suggests, erase parts of the Declaration in order to make it fit Hannah-Jones’s essay or amend the Thirteenth Amendment to make it harmonize with an essay arguing that ‘mass incarceration and excessive punishment is the legacy of slavery.’ Historians, journalists, and politicians frequently accuse one another of twisting history to advance political agendas—and the accused parties always deny the charge. By contrast, the 1619 Project’s curriculum openly encourages such historical revisionism. Its ‘reading guide‘ aims to ensure that students don’t miss core partisan talking points. Jamelle Bouie’s ‘Undemocratic Democracy,’ for example, an essay that draws a line from John Calhoun’s nullification philosophy to Eric Cantor’s hardball budget-negotiation tactics, asks: ‘How do nineteenth-century U.S. political movements aimed at maintaining the right to enslave people manifest in contemporary political parties?’ Students must not miss the point that everything that Republican politicians do, even if ‘the goals may be color blind,’ is ‘clearly downstream of a style of extreme political combat that came to fruition in defense of human bondage.’ For the essay ‘Capitalism: In Order to Understand the Brutality of American Capitalism, You Have to Start on the Plantation,’ the reading guide asks: ‘What current financial systems reflect practices developed to support industries built on the work of enslaved people?’ One answer, suggested in the key terms, is home mortgages—because slaves were once used as collateral. Another acceptable answer is the collateralized debt obligation, a complex structured-finance product developed in the 1980s—because slave-traders had securitized assets and debts (though, the author admits, they were not the first in history to do so).” Mr. Eden is, of course, leaving out quite a bit. He chose, for example, what he saw as the most provocative student activity, not the far more numerous noncontroversial ones. He also leaves out that the reading guide is providing questions students should answer while reading the essays, so they know and understand the points of the essays, not so they are indoctrinated into a certain viewpoint as he seems to be suggesting. This particular critique doesn’t strike me as serious in any way. It is merely an ideological stance.

Professor Ibram X. Kendi defends the project. In a Twitter thread, he writes:

At least part of Professor Kendi’s critique seems to be of the peer review process, but he seems upset that other historians have decided to critique the revisionist viewpoint.

Professor Adolph Reed, Jr. is a political scientist at the University of Pennsylvania. In this interview he also criticizes the 1619 Project. The interviewer says, “Let me ask a little bit about your initial reaction to the 1619 Project. I have spoken to several historians who concentrated their criticism on Nikole Hannah-Jones’ lead essay, which is meant to frame the whole thing, and also Matthew Desmond’s claim that American capitalism is basically the direct descendent [sic] of chattel slavery. Maybe you can help us to understand the rest of the magazine, which is being pushed as a curriculum for school children. It seems to me that what the rest of the essays do is focus on a particular social problem—traffic jams in Atlanta, lack of national healthcare, high sugar in the American diet, and so on—and argue by implication that that’s all coming out of slavery. The dominant tendency in academia is to attribute all social problems to race, or to other forms of identity, but the 1619 Project goes farther still, saying that they are all rooted in slavery.” Professor Reed responds, “I didn’t know about the 1619 Project until it came out, and frankly when I learned about it my reaction was a big sigh. But again, the relation to history has passed to the appropriation of the past in support of what whatever kind of ‘just-so’ stories about the present are desired. This approach has taken root within the Academy. It’s like all bets are off. Merlin Chowkwanyun and I did an article a few years ago in the Socialist Register that’s a critique of disparitarianism in the social sciences, by which this or that disparity has replaced the study of inequality and its effects. As Walter Benn Michaels said, and as I have said time and time again, if anti-disparitarianism is your ideology, then for you a society qualifies as being just if 1 percent of the population controls 90 percent of the wealth, so long as that within that 1 percent 12 percent or so are black, etc., reflecting their share of the national population. This is the ideal of social justice for neoliberalism. There’s no question of actual redistribution. What are the stakes that people imagine to be bound up with demonstrating that capitalism in this country emerged from slavery and racism, which are treated as two different labels for the same pathology? Ultimately, it’s a race reductionist argument. What the Afro-pessimist types or black nationalist types get out of it is an insistence that we can’t ever talk about anything except race. And that’s partly because talking about race is the things they have to sell. If you follow through the logic of disparities discourse, and watch the studies and follow the citations, what you get is a sort of bold announcement of findings, but finding that anybody who has been reading a newspaper over the last 50 or 70 years would assume from the outset: blacks have it worse, and women have it worse, and so on. It’s in part an expression of a generic pathology of sociology, the most banal expression of academic life. You follow the safe path. You replicate the findings. But it’s not just supposed to be a matter of finding a disparity in and of itself, like differences in the number of days of sunshine in a year. It’s supposed to be a promise that in finding or confirming the disparity in this or that domain that it will bring some kind of mediation of the problem. But the work never calls for that.” In response to Ms. Hannah-Jones’s reference to “founding myths,” he says, “Every state is going to have its founding myths, if you think of them as ideals. But what is so important about Jim Oakes’ book, Scorpion’s Sting, is that you can see this tension about human equality that was rooted in the founding documents and debates. It’s especially ironic to consider, for instance, the three-fifths compromise to the Constitution, which was an expression of exactly the opposite political value that the people who invoke it as part of an Afro-pessimist discourse claim. These people are kind of just making it up as they go, or reinventing the past to suit the purposes of the present. Right from the outset. Those first 20 people weren’t slaves. There wasn’t chattel slavery yet in British North America. But the 1619 Project assumes, in whatever way, that slavery was the natural condition of Africans. And that’s where the Afro-pessimist types wind up sharing a cup of tea with the likes of James Henry Hammond.” When the interviewer asks, “Let me ask you about what in academia is called ‘critical race theory’ and how you see it at work in the 1619 Project,” Professor Reed responds, ” It’s another expression of reductionism. On the most pedestrian level it’s an observation that what you see is a function of where you stand. At that level there’s nothing in it that wasn’t in Marx’s early writings, or in Mannheim. But then you get an appropriation of the standpoint theory for identity that says for example, all blacks think the same way. It’s taxonomic, a reification. So the retort to that critique has been “intersectionality.” Yes, there’s a black perspective, but what you do is fragment it, so there are multiple black perspectives, because each potential—or each sacralized—social position becomes discrete. That’s what gives you intersectionality. But listening to how people talk about intersectionality, it just seems like dissociative personality disorder. How do you carve out when your male is talking, and your black is talking, and when your steelworker is talking? It seems like the kind of perspective that can work only at a level of abstraction at which no one ever asks to see something concrete. Herbert Butterfield, in The Whig Interpretation of History, back in 1931, had this great criticism of what he calls concepts that are incapable of concrete visualization. But we have this world of theory where big cultural abstractions kind of cross-pollinate and relieve the theorists of historical work.” The interviewer then says, “We’ve spoken to a number of leading historians, including James McPherson, James Oakes, Gordon Wood and Victoria Bynum, and Hannah-Jones launched into a Twitter tirade against them, dismissing them as ‘white historians.’ She is not a historian, but she is the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation ‘genius grant,’ just like Ta-Nehisi Coates and Ibram X. Kendi have been in recent years.” Professor Reed says, “I have spent most of my adult life trying to avoid the kind of old-fashioned Stalinist conspiracy theory, but it’s getting hard. My dad used to say that in one sense ideology is the mechanism that harmonizes the principles that you want to believe with what advances your material interest. And so I understand that the people of MacArthur, for instance, think they’re doing something quite different. But when they look for voices, the voices that they look for are the voices that say ultimately, ‘Well it’s a tragedy that’s hopeless. We have to atone as individuals. Do whatever you can do to confront disparity.’ I’ve been joking for a number of years that here at Penn the university administration has three core values: Building the endowment, already at $16 billion. Buying up as much on the real estate as they can on both sides of the Schuylkill River. And diversity. And they’re genuinely committed to all three of those because they think that part of their mission is to make the ruling class look like the photo of America. I made a reference once to Coates being an autodidact, and what I meant by that was that he did not know history, that he’s not a historian. Kendi’s book, I don’t know anyone who has actually read it.” Regarding Ms. Hannah-Jones’s claim that racism is in the DNA of the country, Professor Reed says, “The only place that can lead, if it’s impermeable, if it’s immutable, is race war. The ‘legacy of slavery’ construct is also one I’ve hated for as long as I can remember because, in the first place, why would the legacy of slavery be more meaningful than the legacy of sharecropping and Jim Crow and the legacy of the Great Migration? Or even the New Deal and the CIO? But what’s ideologically useful about the legacy of the slavery trope is that it can mean two seemingly quite different things. One is that it can be invoked as proof that blacks are inferior, because slavery has forged an indelible mark. Or it can be invoked as a cultural pathology argument. But it’s a misunderstanding to assume that there’s a sharp contrast between cultural arguments about inequality and biological arguments. They’re basically the same. If you go back to the highwater mark of race theory at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, you don’t need to have a theory of biological heredity to make a deterministic claim. You can shed the need for complex biological argument and just say that the cultures are different, and the culture decrees these kinds of inadequacies.”

Michael Harriot is a journalist with “The Root” and says, in this article, “Some white people are upset that the New York Times‘ 1619 Project isn’t centered in whiteness.” He writes, “There is no such thing as an ‘exact’ measurement. All measurements are subject to some uncertainty. One of the world’s most valuable pieces of metal resides under three vacuum-sealed glasses that resemble the formal pound cake dish your grandmother only breaks out for funerals of pastors, high-ranking deacons, and people who earned permanently reserved front-row pew status. Since 1889, the International Prototype Kilogram has been the physical standard by which the standards for mass and volume are calibrated. It quite literally defined the kilogram for the world. The science of metrology is based on the mathematical principle that no measurement is exact. Everything we measure is, essentially, an imprecise comparison to something else and is, therefore subject to uncertainty. So when the scientific community realized that the mass of the IPK had actually decreased by the equivalent of a single eyelash, they decided to revise the scientific definition of the kilogram. And because the tiny piece of Parisian metal represents the definition of the kilogram, it technically didn’t get smaller. Scientifically speaking, every other kilogram in the world gained an eyelash worth of weight. So, on May 20, 2019, the IPK became irrelevant.” After that amusing story he says, “There is no such thing as ‘American history.’ What we call American history is actually white history and is subject to uncertainty. Even noted historians such as Carter G. Woodson, Lerone Bennett Jr., and The Root founder Henry Louis Gates are considered scholars of ‘black history,’ which is different from ‘American history.’ While all history is relative, in this country, white people have always defined the unit of measurement we call ‘American.’ The academic and intellectual pursuit of black people’s history is viewed through a Caucasian-colored lens that turns reality into an ahistorical fairy tale whose protagonists are the fair-haired, valiant champions of liberty and democracy for all. The white version of black history doesn’t acknowledge that the 41 of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence owned slaves. Their history ignores the fact that George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin considered slavery a ‘moral depravity‘ but supported the insidious institution anyway. Contrary to publicly available data, white historians’ version of America’s past never reveals that 75 percent of white people believed civil rights protesters were communists and 85 percent of whites thought civil rights protesters were ‘hurting the negro cause.’ Whiteness has always been the standard unit of measurement. So when the New York Times created the 1619 Project to commemorate the arrival of the first Africans in the American colonies, of course white people were upset. Andrew Sullivan (whose status as an intellectual rests solely on the notion of saying stupid shit in a British accent) called the Times’ journalistic historiography an act of neo-Marxist ‘liberal activism.’ New York magazine’s Eric Levitz said it was steeped in ‘anti-white politics.’ And, on Saturday, a group of white historians’ crusade to re-reframe the undertaking in their own likeness culminated in a letter to the Times asking: ‘But-what-about-wypipo?’ The letter was written by Victoria Bynum, Texas State University; James M. McPherson, Princeton University; James Oakes, City University of New York; Sean Wilentz, Princeton University; and Gordon S. Wood of Brown University. Their whole consternation came solely from the fact that the NY Times’ comprehensive historiography wasn’t centered in whiteness. Seriously, that’s it.” Seriously, that’s not it. Mr. Harriot unfairly libels some eminent scholars who are the opposite of what he claims. While I do think he has a point regarding what the history profession used to be, it seems to me that in recent years it doesn’t resemble that anymore, at least with the historians it has been my pleasure to meet.

Mr. Harriot continues, “Led by McPherson, the League of Concerned Caucasians have individually and collectively expressed outrage that they were not asked to contribute to the project. As if they were the keepers of America’s history, they want a list of the historians who did partake in it, along with corrections of what they call ‘misleading’ information and ‘factual errors.’ However, the errors and misinformation cited by the ignoble adversaries of black thought are all based on white Americans’ perception of history. Their main quibble with the 1619 Project is that it ‘intended to offer a new version of American history in which slavery and white supremacy become the dominant organizing themes,’ which upsets the prevailing narrative. ‘Some of the other material in the project is distorted,’ they write, ‘including the claim that ‘for the most part,’ black Americans have fought their freedom struggles ‘alone.’’ To be fair, that is a valid criticism. There were scores of abolitionists, civil rights protesters, and allies who were white. We can’t forget that Kim Kardashian bravely took a private jet to talk to Donald Trump after black women activists made her aware of Cyntoia Brown. I personally know someone who affixed a ‘Black Lives Matter’ bumper sticker to his Honda Civic. But compared to the sheer number of apathetic white people who actively didn’t do shit to fight slavery, Jim Crow and inequality, the sheer number of white freedom fighters is minuscule, which is why—and pardon me while I switch to all caps—THEY SAID: “FOR THE MOST PART!’ But again, history is subjective.” He continues to libel these historians and has no substantive criticism of them outside his sarcasm.

He continues, “The White Power Rangers pointed out that the 1619 Project painted Abraham Lincoln as a white supremacist, citing the fact that Lincoln had a black friend (Frederick Douglass). The group considers this ‘misleading,’ in spite of the fact that Lincoln himself said in 1860: ‘I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the fooling of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge DOUGLAS, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position. I have never said anything to the contrary.’ How is that not the definition of white supremacy? But they insist that they know what Lincoln meant so it doesn’t matter what he said. Apparently, the Legion of Extraordinary Revisionists assumes that a random gaggle of negro brains couldn’t possibly possess the requisite historical clairvoyance demonstrated by their superior Caucasian minds.” Beside his continued libel, he completely mischaracterizes what the historians said and even has the date of his Lincoln quotation wrong. This is why most journalists are unsuited to comment on history. He has no idea that while we today would regard Lincoln’s defense of himself, in this carefully cropped and cherrypicked quote, from a highly race-baiting attack as racist, in 1858, the actual year he said it, Lincoln was considered to be advocating for equal rights for African Americans. It also ignores the fact that Lincoln’s views evolved over time so that by the end of his life he was advocating limited African American suffrage. If he doesn’t trust white historians on this, he could ask Professor Edna Greene Medford of Howard University or Professors Nell Irvin Painter or Thavolia Glymph, referred to earlier in this post. Or he could ask Henry Louis Gates, founder of the publication for which he writes.

Mr. Harriot then writes, “Their final point is one that was recently explained to me by Dr. Greg Carr, Howard University’s chair of Afro American Studies and the aforementioned Henry Louis Gates. Namely, that the prospect of the British crown eliminating slavery was a major factor in the American Revolution. There is a whole book about the subject—Gerald Horne’s The Counterrevolution of 1776. The white people say it’s a lie. ‘This is not true,’ they say, adding: ‘If supportable, the allegation would be astounding—yet every statement offered by the project to validate it is false.’ ” As I’ve discussed on this blog several times already, there’s been no hard evidence put forward that the colonists were acting to protect slavery. Even Ms. Hannah-Jones has backtracked from her original claim. Protection of slavery was not a major factor in the America Revolution at all.

Mr. Harriot concludes, “Ultimately, these supposed scholars contend that their viewpoint is the only perspective from which American history can be correctly understood. They are arguing that history, unlike every other academic and intellectual pursuit, is not subjective. According to them, black scholarship is invalid if it contextualizes whiteness in any other way than as the altruistic, magnanimous gravitational force that formed the undefeated world champion of liberty and justice for all—even when it didn’t.” Of course, that’s nothing like what these eminent scholars are contending. But the truth doesn’t seem to matter to Mr. Harriot.

Finally, we have this interview with Professor Dolores Janiewski of Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. She says, “That’s been one of the submerged things in American thinking for a terribly long time. Identity politics in the recent period has buried class under race and gender and so forth. I was an intersectional person before the word got invented, because I was writing about race, gender and class in the 1970s. I went through the two main articles in the 1619 Project, and what I was immediately struck by from the beginning is it leaves out indigenous people. It starts with slavery in 1619. Hannah-Jones only has one or two paragraphs about the Indians getting removed from Georgia. But in the course I’ve just been teaching, in 1512, the leader of the Taino people in the Caribbean was burned at the stake for leading an indigenous rebellion against the Spanish. Part of the way capitalism develops in North America is about dispossession. That’s also true in the British Isles, dispossessing the Highlanders, dispossessing the Irish. The first plantations are actually in Ireland. The British take over and deprive the peasants of the land. It’s a much more complicated story than reducing it down to slavery being the engine of capitalism.” In response to Ms. Hannah-Jones saying slavery in the United States was different, Professor Janiewski says, “Yes, it’s an exceptionalist, US original sin story. She ignores slavery in Cuba, Brazil, other places. And if you want to talk about original sin, America has many original sins, one of them is the dispossession of the indigenous people.” In response to Ms. Hannah-Jones saying slavery is part of America’s DNA, Professor Janiewski says, “It’s somewhat of an ahistorical concept. A lot of the colonising in America was because those people were driven off the land in Europe. They’re indentured servants. Two thirds of the people who crossed the Atlantic in the first 200 years are unfree, some of them are indentured and some of them are slaves. A really good book by Edmund Morgan called American Freedom, American Slavery, which Hannah-Jones doesn’t seem to look at, is about how, in the first period, they don’t have permanent slavery. So those people coming in 1619 are, in some sense, treated like indentureds. Eventually they can become free along with the indentured white people, and then they become problems. The poor people, black and white, share common interests. By the late 1600s the wealthy Virginia planters start passing laws to distinguish between black and white, and they create permanent slavery for the African that will be inherited by the children. They make race a privilege: a sign of freedom versus slavery. They change the laws to break up those alliances between poor whites and poor blacks. And they treat women differently: white women are assumed not to have to work in the field as part of that new set of laws, and black women are assumed as laborers. Slavery isn’t a fully developed system from 1619; it evolves. Likewise, Indians were initially seen as whites and then, by the 1850s, they’re seen as ‘redskins.’ So, race is an evolving system developed by people with an economic stake in evolving it.” The interviewer asks, “Hannah-Jones says that after the Civil War, ‘White southerners of all economic classes … experienced substantial improvement in their lives even as they forced black people back into a quasi-slavery.’ What do you make of these statements about this period?” Professor Janiewski responds, “Well, it’s a pretty broad generalisation. If you’re talking about economics, the southern income is half of the national average at 1900. The South doesn’t really recover from the destruction of the Civil War. In the 1930s poverty in the South is one of the major problems for Roosevelt. So, it’s not true that every white person’s life improved. In some sense poverty helped to entrench the racial system over time, because you had one thing that made you better: being white. It wasn’t that you were economically, necessarily, better off. The ideology of white skin privilege was part of the system, but it doesn’t mean in material fact that was actually the case. My family were the town liberals in Okeechobee, Florida, and my mother would talk about poor whites, the ones who didn’t have shoes and had never left the county. She was a great teacher and she would take kids to the ocean which was 36 miles away; they’d never seen the ocean. She was a New Deal liberal, French Canadian, relatively enlightened in racial and class terms; she organised a teachers’ union and tried to integrate the schools and make sure black teachers didn’t lose their jobs.” She says of the 1619 Project, “They’re sort of running roughshod over a lot of history in a few paragraphs. It’s not an in-depth analysis.” Which, of course, it’s not meant to be. She also says, “There were Communists in the 1930s defending the rights of blacks in one way or another, but there were also relatively progressive whites, Christians and people criticising racism. So, it’s not just blacks alone. The NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] was founded by a group of progressive whites and blacks in the North. In North Carolina in the late Reconstruction era, Albion Tourgée, a white progressive from the South, tried to organise poor whites and blacks for the Republican Party in 1868, helped write a non-racial state constitution, then became a judge and had poor whites and blacks as his allies. Then, systematically, the Klan lynched a poor white activist, lynched some of the blacks he knows, and then tried to assassinate Tourgée. Ultimately, he’s forced out of North Carolina in 1878. He then wrote an antilynching column, he tried to challenge segregation in the Supreme Court, then he helped to create the predecessor to the NAACP. There are probably about 20,000 blacks who are killed and 5,000 whites who are killed in this Reconstruction period by the Klan and those kinds of groups. It’s like death squads in Latin America; you go after activists and organisers using terror. White activists were seen as race traitors.”

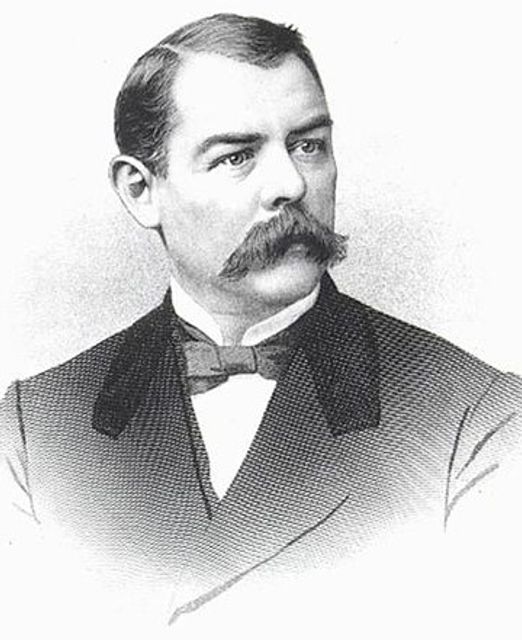

Albion W. Tourgée

Albion W. TourgéeShe says of the project, “They’re imposing identity politics all the way back. And in certain times, people don’t even think in terms of categories of white and black. They have to be taught that skin color is significant. Racial identity politics is real in terms of what it does to you, but also unreal because it has no actual scientific basis, although some people keep trying to reinvent it over and over again. Saying racism is in America’s ‘DNA,’ I don’t think Hannah-Jones really meant it, I think that’s just a metaphor. But still, it’s using a genetic explanation for this stuff, which isn’t necessarily true.”

I think the 1619 Project is doing some very good things, but I also think the historians have identified some real weaknesses that need to be addressed. By putting up a barrier and attacking the historians, the project and its defenders are actually engaging in a self-defeating exercise. They should thank these historians and make changes to incorporate the factual criticisms and acknowledge and address the interpretive differences. It will only make their case stronger. I’m a fan of the project and I want their products to be as accurate as possible.

Very good summary

I have also been following this controversy. I appreciate your summaries of some of the recent claims and counterclaims. I generally liked “1619” but I have some issues with some of the articles. On the other hand, I have seen the series as journalism, not academic historical writing, and evaluated it as such.

Rosen’s argument that the five historians should have approached her privately rather than sending a letter to the editor seems off to me. If they were approached by her and they refused to offer info until after the series was published, perhaps she might have a point. But they are under no obligation to keep criticism under wraps after the articles are published. I also worry that some of the defense of the series has quickly descended into ad hominem attacks.

I agree completely, Pat. In fact, I’m putting the finishing touches on another lengthy blog post that addresses this topic directly.

Thanks for putting all this together, Al – I’ve been following the debate from the sidelines and I think this is a very thoughtful and concise summary. Looking forward to your future comments 🙂

Thanks, Keith. I appreciate the comment. A new one is about to come out.