We begin this week’s roundup with this article out of King George County in Virginia. “On a 3–2 vote, the King George County Board of Supervisors voted this week to move a monument that honors Confederate soldiers off the courthouse lawn. The action was applauded by members and friends of the King George chapter of the NAACP who’d been asking the county to move the obelisk from public property for more than 18 months. On Tuesday, Robert Ashton, NAACP vice president, asked the supervisors once more to ‘stop the politics and do the right thing by moving the monument to a cemetery where it belongs.’ ‘The Confederacy was a racial institution,’ Ashton said, ‘therefore any statue or monument honoring the Confederacy endorses racism.’ David Jones, who is white, was the first to publicly bring the issue before the board in July 2020, and on Tuesday, he again called the monument the ‘Confederate traitors’ memorial.’ His great-great-grandfather was among those who fought for the Confederacy, and while Jones said he respects his ancestor, he would never support his decision to take up arms to keep Black people enslaved. He noted the dozens of times the preservation of slavery was cited in secessions documents for Southern states, including Virginia.”

The opponents of moving the racist symbol predictably lied about moving a monument being erasing history. “Other King George residents, such as Steve Davis, were opposed to removing objects they deemed historical. ‘It saddens me to see the history of this country erased,’ Davis said, adding that modern-day residents won’t be able to teach about injustices to the African-American community if all traces of its existence are gone. ‘How can we find our way in the future if we don’t know where we’ve come from?’ ” That’s a lying argument. Moving a monument is not erasing history.

This article from Montgomery, Alabama, tells us, “Alabama’s capital city last month removed the Confederate president’s name from an avenue and renamed it after a lawyer known for his work during the civil rights movement. Now the state attorney general says the city must pay a fine or face a lawsuit for violating a state law protecting Confederate monuments and other longstanding memorials. Montgomery last month changed the name of Jeff Davis Avenue to Fred D. Gray Avenue. Gray, who grew up on that same street, represented Rosa Parks and others in cases that fought Deep South segregation practices and was dubbed by Martin Luther King Jr. as ‘the chief counsel for the protest movement.’ The Alabama attorney general’s office sent a Nov. 5 letter to Montgomery officials saying the city must pay a $25,000 fine by Dec. 8, ‘otherwise, the attorney general will file suit on behalf of the state.’ ” Alabama feels it must protect symbols of racist oppression.

The article continues, “Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed said changing the name was the right thing to do. ‘It was important that we show, not only our residents here, but people from afar that this is a new Montgomery,’ Reed, the city’s first Black mayor said in a telephone interview. It was Reed’s suggestion to rename the street after Gray. ‘We want to honor those heroes that have fought to make this union as perfect as it can be. When I see a lot of the Confederate symbols that we have in the city, it sends a message that we are focused on the lost cause as opposed to those things that bring us together under the Stars and Stripes.’

The article also tells us, “Reed said they knew this was a possibility when the city renamed the street. Donors from across the country have offered to pay the fine for the city. He said they are also considering taking the matter to court. ‘The other question we have to answer is: Should we pay the fine when we see it as an unjust law?’ Reed said. ‘We’re certainly considering taking the matter to court because it takes away home rule for municipalities.’ Alabama’s capital city is sometimes referred to as the “Cradle of the Confederacy” because it is where representatives of states met in 1861 to form the Confederacy, and the city served as the first Confederate capital. The city also played a key role in the civil rights movement — including the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The Montgomery County school system has voted to rename high schools named for Davis and Confederate General Robert E. Lee — although the names have not yet been changed.” Another example of an unjust law that aids racism.

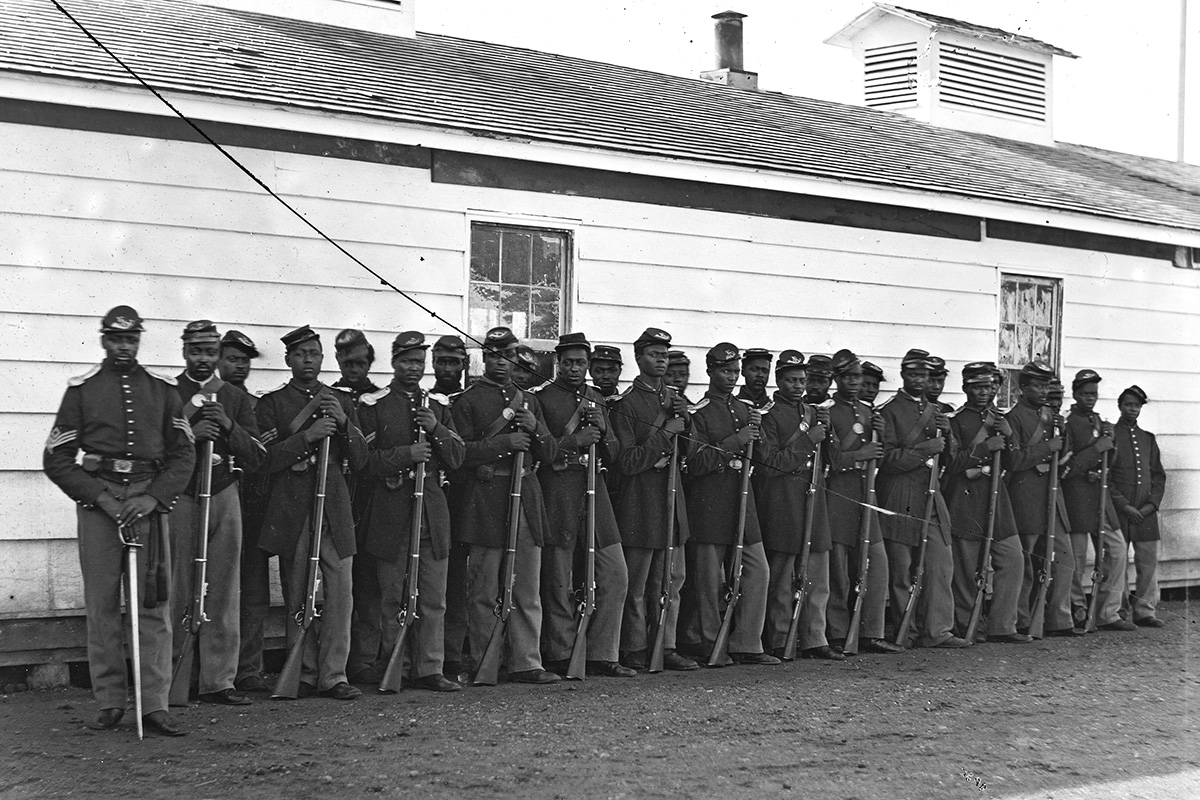

This article out of Natchez, Mississippi, shows how racist neoconfederates are. ” ‘Wilson Brown, born in Natchez, was a Navy Landsman and was one of the eight African Americans who was awarded the Navy and Marine Medal of––’ ‘I need a [n-word] on line 2. A [n-word] on line 2 please,’ a male voice interrupted Natchez Monument Committee Member Deborah Fountain, a Black woman. Fountain tried to continue with her presentation on the history of the U.S. Colored Troops, but she was interrupted again with more racial epithets from the virtual attendees of a public town hall meeting on Nov. 10, 2021. Everyone could hear the insults, with many attendees gasping in shock and disgust from the repulsive interruption. ‘[n-word] boy,’ a different male voice speaks up. ‘[n-word],’ a female voice added. ‘[n-word],’ she repeats. It was silent for a moment before Fountain made a fourth attempt to finish her presentation. There was a slight catch in her voice, but she powered through despite the moment. The program organizers manage to get the trolls booted for the rest of the night, but one can never underestimate the overt racism that makes itself known during events that celebrate and uplift the Black and brown Mississippians of the past and present.” And these folks are cowardly. They do this on a virtual meeting where they can’t be seen or identified. If they are in public they make sure they are in a gang of fellow racists, usually armed. Scratch a confederate heritage advocate and you will normally find a racist.

The article continues, “The Natchez U.S. Colored Troops Monument Committee hosted the town hall meeting to get community input on a potential monument to honor and showcase the names of more than 3,000 African American men who served with the colored troops at Fort McPherson in Natchez during the Civil War and the Navy men who served and were born in Natchez. The southwest Mississippi city of about 15,000, which gained its initial wealth and power from plantations worked by enslaved Black people, has long celebrated its Confederate heritage with dress-up pageantry. But in recent years, it has started publicly grappling with its history, including as the site of the second largest domestic major slave market in the Deep South at Forks of the Road. Now, organizers of the town hall believe it should celebrate local Black soldiers’ role in the downfall of the Confederacy and the liberation of enslaved Black southerners. ‘On Jan. 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It declared all persons held as slaves, in the rebellious states, to be free,’ History and Research Chairman Deborah Fountain told the audience. ‘And number two, it announced the acceptance of Black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators.’ By the end of the Civil War, around 180,000 Black men had served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and 20,000 Black men served in the Navy. On May 22, 1863, the U.S. War Department issued General Order 143, which created the United States Colored Troops. The Union army took control of the Mississippi River following the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. During the occupation of Vicksburg, colored troops performed duties such as drill, police duty, picket-line duty outside the city, mandatory school attendance and service details around town, the National Park Service reports. ‘Officers thought the United States Colored Troops required more supervision and detailed instruction than other troops. The USCT were also held to a much higher standard than their white counterparts and punished more frequently if they failed at their various tasks,’ the site reads.”

We learn, “On July 13, 1863, nine days after the Fall of Vicksburg, Union troops arrived in Natchez and General Ulysses S. Grant established union headquarters at Rosalie Mansion. Three weeks later, U.S. Colored Troops regiments began to be raised in Natchez. ‘A large number of these Black men who enlisted were from Natchez, or many had bravely left plantations in the Natchez district and surrounding counties and fled to Natchez and enlisted,’ Fountain said. During the fall of 1863, soldiers began to work on the construction of a five-sided earthwork fortification named for Gen. James Birdseye McPherson and included the Marine hospital in the northwest corner. Soldiers received orders to demolish the slave pin at the Forks of the Road and use the wood for the construction of the fort and its barracks, she said. More than 3,000 U.S Colored Troops served in six regiments at Fort McPherson. Those regiments included the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, the 58th U.S. Colored Infantry, the 70th U.S. Colored Infantry, the 71st U.S. Colored Infantry, the 63rd U.S. Colored Infantry and the 64th U.S. Colored Infantry. The monument will honor these regiments. Natchez’ population is 63% Black, and the committee is encouraging families to look through their family trees and visit the National Park Service’s website to search for ancestors who served in the military during the 1860s on the United States Colored Troops list. ‘It is believed that up to 90% of individuals of long-standing Black families in Natchez may be descendants of the Natchez colored troops, soldiers and sailors, but may not know it,’ Fountain said.”

Thanks for including the report on the community meeting for the Natchez U.S. Colored Troops Monument Project. It is appreciated.

You’re very welcome.

[…] Mackey continues his weekly updates on the State of Confederate Heritage over at Student of the American Civil […]