On Saturday, February 20, 2016 I attended the Road From Appomattox symposium held at the Library of Virginia in Richmond. The symposium was jointly sponsored by the American Civil War Museum and the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History at the University of Virginia. It was great to see some friends again, and it’s always wonderful to be back in the Old Dominion. The symposium had some very well known Civil War historians connected to it. Waite Rawls and Christy Coleman, the co-CEOs of the American Civil War Museum were on hand, as was John Coski, the well-respected historian who wrote the definitive book about the confederate flag. Presenting were Dr. Ed Ayers, Dr. Doug Egerton, Dr. Mark Grimsley, Dr. Caroline Janney, and Dr. Gary Gallagher.

There were some really interesting takeaways from the symposium. For example, Dr. Ayers made the point that if we look at the results of the 1864 election we see that at that late date in the war almost half the men in the loyal states did not approve of what Lincoln was doing to the point where they preferred a Democrat in the White House–a Democrat who would probably repudiate emancipation and if he ended the war would do so with slavery intact. George McClellan would not have supported voting rights for black men, nor any semblance of equal rights for African-Americans. Contrast that with Lincoln’s call, in his last public address, for limited suffrage for black men. Those men who voted against Lincoln in 1864 were not going to change their views overnight, so already at the end of the Civil War you have almost half the white electorate in the North who are not supportive of black civil rights. They will have an effect on Reconstruction and whether or not it will continue. The culmination of the struggle over Reconstruction ultimately depended on those voters who voted against Lincoln. The problem for the Republicans in Reconstruction was the white North was hopelessly divided whereas the white South was, for the most part, united against them.

Dr. Egerton made the claim that with Reconstruction a new war was beginning. There were a number of conventions of African-Americans throughout the United States calling for voting rights, equal pay for USCT soldiers, and black commissioned officers, and then later for equal rights for African-Americans. The overwhelming number of USCT were black southerners who stayed in the South after they mustered out. These former soldiers, and others, became activists for black equality. According to Dr. Egerton, 53,000 black activists were targeted for assassination by white southerners. He also made the point that the Indian Wars in the West damaged Reconstruction because it siphoned off soldiers who could have been used in the South to protect Freedman’s Bureau employees and others.

In his presentation, Dr. Grimsley compared how the United States approached war against white southerners with how it approached war against Native Americans. In the American experience, he said, atrocities tend to occur overwhelmingly in the context of interracial struggles. That’s why there were hardly any atrocities against white southerners in the Civil War, but a number of atrocities against blacks by confederate soldiers and some atrocities committed by US soldiers against Native Americans. Most atrocities, like the My Lai massacre under Lt. William Calley, take the form of crimes of obedience. In the Civil War, confederate soldiers killed USCT without the need for orders from higher authority. Actions against Native Americans also would get out of hand without the need for orders from higher authority.

Dr. Janney looked at Civil War veterans in the Spanish-American War. She told us that both sides were working to ensure their version of Civil War memory would prevail. The Spanish-American War provided confederate veterans an opportunity to prove their loyalty. White southerners claimed it vindicated their claims in the lost cause that they hadn’t been traitors, that they fought for the same things, for the principle of self-government and for liberty. In the spirit of reconciliation, President William McKinley proposed offering aid in caring for graves of confederate veterans and providing Federal pensions for surviving confederate veterans. Union veterans found the proposal for pensions to be insulting to their sacrifices. They had no problems with Federal funds to assist in caring for the graves of those who had been “deluded and deceived into joining the rebellion,” as long as Union graves got more money and more distinction because of the difference between those who fought to break up the country and those who fought to save the country. In the end, the confederate veterans voted to reject McKinley’s offer of aid for cemeteries and the offer for pensions as well.

Dr. Gallagher strenuously objected to the idea of a “Long War” in which the struggle of the Civil War continued through Reconstruction. He made the point that the end of the Civil War was the end of the war. He also objected to the idea that Reconstruction represented a lost moment for African-Americans. He said three landmark amendments, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, came out of Reconstruction. Reconstruction ultimately ended in a failure of equal rights for African-Americans because of three factors: the hard fiscal realities of the time, the long-standing American opposition to long-term military occupation in peacetime, and the profound racism that existed throughout the United States.

This was an excellent symposium. C-SPAN recorded the presentations, and I’ll make another post once the presentations air.

During the symposium we took the opportunity to view the Library’s latest exhibit, Remaking Virginia: Transformation Through Emancipation.

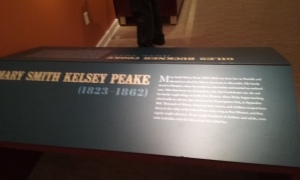

The artifacts on display and the interpretations were really terrific in looking at emancipation in Virginia and how African-American freedom affected the state in Reconstruction and beyond.

It includes two life masks of Abraham Lincoln.

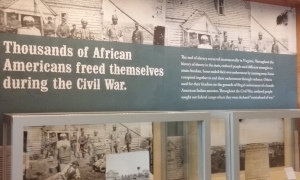

The display covered the actions of black Virginians in freeing themselves.

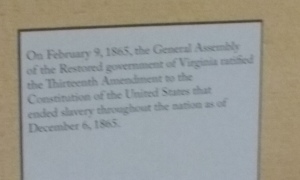

It also covered the actions of the Loyal Government of Virginia in ratifying the 13th Amendment.

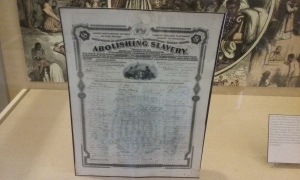

As well as Virginia’s abolition of slavery.

After emancipation, the government set up Freedmen’s Villages to assist the freed people.

The exhibit looks at the 15th Amendment as well as various issues of Reconstruction.

It also looked at Reconstruction violence.

The exhibit is really terrific, and I urge anyone who finds themselves in the area to stop in at the Library of Virginia and check it out.

When the phrase 53,000 blacks were “targeted for assassination” was used does that mean they were actually killed?

I don’t think he meant actually killed, Pat, but I would have to listen to the recording once more to be sure.

One of your photos references an abolition of slavery in Virginia dated March 4, 1864. That has to be by the rump loyalist government, right?

It was by the Loyal Government of Virginia.

Interesting—I had not heard (that I remember) that this had happened.